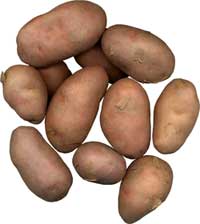

Ad?n Felipe Mej?a, Peruvian poet and philosopher, describes some of the vast array of potatoes in the world thus: "There are enormous sandy potatoes with delicate hues and noble shape. Some are oval and perfect, others like a rolling pin, with no holes, more resistant and dense. Some are round, smooth, grooved and tender. Some have a black skin, and others are white inside. There is an infinite variety, a wide range of tastes! And the yellow potato-that poem-delicate, fine, with tiny holes in its side like the face of an enchanting little girl, the yellow potato gleams like egg yolk."

Ad?n Felipe Mej?a, Peruvian poet and philosopher, describes some of the vast array of potatoes in the world thus: "There are enormous sandy potatoes with delicate hues and noble shape. Some are oval and perfect, others like a rolling pin, with no holes, more resistant and dense. Some are round, smooth, grooved and tender. Some have a black skin, and others are white inside. There is an infinite variety, a wide range of tastes! And the yellow potato-that poem-delicate, fine, with tiny holes in its side like the face of an enchanting little girl, the yellow potato gleams like egg yolk."

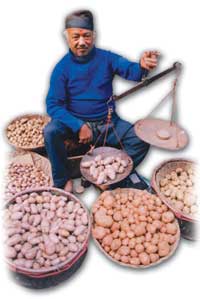

Nepalis tend not to wax too eloquent on the beauties of the spud, but catch them on a sunny winter afternoon, well-fed on carbohydrate a la potato, and they can put up a decent show. Unfortunately, their imagination and tuber-related vocabulary runs out after they meditate on the powdery, delectable taste of potatoes grown in mountain regions like Manang and Khumbu.

But make no mistake. Here in Nepal we have a real reverence for the potato. So, you say, do denizens of lands that can't do without their daily meat-and-potato fix. But this is different. Plain boiled spuds can be delicious, it is true, as are fries, but it takes a particularly obsessive evil genius to do things as diverse to the potato as we do here-the delicate reek of aloo tama or that gem of gustatory inspiration aloo ko achar, the complex flavours aloo masyaora or the beautifully simple aloo dum. Your mouths watering yet?  People in Palpa are proud of their aloo chykauni, plains Nepalis enjoy aloo bhujiya with roti, those living in the highlands salivate over aloo bhat and aloo daal. Sometimes even better on a cold, dark winter's day is plain usineko aloo, boiled potatoes with marcha-chillies pounded with salt and garlic.

People in Palpa are proud of their aloo chykauni, plains Nepalis enjoy aloo bhujiya with roti, those living in the highlands salivate over aloo bhat and aloo daal. Sometimes even better on a cold, dark winter's day is plain usineko aloo, boiled potatoes with marcha-chillies pounded with salt and garlic.

In the realm of the spud, Nepal might well be tops-the French have been trying for centuries to do something innovative with the tuber king and have managed one decent item, a potato souffle made with milk and a nice Gruyere. Food writer and philosopher MFK Fisher writes in The Gastronomical Me that the first time she ate one of these, it was like a revelation. (Although what is French about French Fries, we never quite figured out.) Potatoes had until then always seemed dissatisfying, somehow underdressed. Nepal's achievement is not to be underestimated.

In places like Nepal and Bhutan, the big promoters of potatoes in the 18th century were monastic groups. Robert Rhoades, an anthropologist and former Peace Corp volunteer to Nepal, believes that potatoes made keeping oneself fed a less onerous, time-consuming task, as a result of which people in monastic communities had more time to devote to arts and craft.  The influence of potatoes on the eating public here goes even further. The development of the spud in this country might be said to have paralleled that of the Nepali nation state. The first recorded reference to potatoes in Nepal is, after all, in 1793. (See box) Given that potatoes only reached the Old World from their birthplace in the Andes in the 17th century, many Nepalis probably had their first taste of the tuber and nationhood about the same time. Coincidence? We think not. A decade after Colonel Kirkpatrick wrote of the potato in Nepal, in 1803 another British traveller, Francis Buchanan Hamilton wrote thus in An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal and of the Territories Annexed to this Dominion by the House of Gorkha: "In the hilly parts of the country (Solanum tuberosum) has been introduced, and grows tolerably; but it does not thrive so well as at Patna, owing probably to a want of care."

The influence of potatoes on the eating public here goes even further. The development of the spud in this country might be said to have paralleled that of the Nepali nation state. The first recorded reference to potatoes in Nepal is, after all, in 1793. (See box) Given that potatoes only reached the Old World from their birthplace in the Andes in the 17th century, many Nepalis probably had their first taste of the tuber and nationhood about the same time. Coincidence? We think not. A decade after Colonel Kirkpatrick wrote of the potato in Nepal, in 1803 another British traveller, Francis Buchanan Hamilton wrote thus in An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal and of the Territories Annexed to this Dominion by the House of Gorkha: "In the hilly parts of the country (Solanum tuberosum) has been introduced, and grows tolerably; but it does not thrive so well as at Patna, owing probably to a want of care."

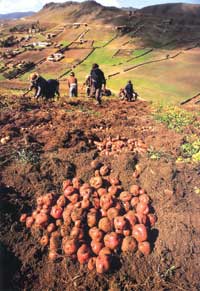

Originally cultivated in Peru and the temperate climate of the Andes, the potato found its way to Europe via the Spanish conquistadors in the 17th century. Research is divided over whether it was the Portuguese or the Spanish who first introduced the potato to India shortly thereafter. Today, India is one of the world's largest producers of potato, after China. "The British in India grew the potato in their kitchen gardens in summer hill stations like Shimla and Darjeeling. It probably arrived in Ilam via Darjeeling, and to western Nepal via Shimla and Naintal through seasonal migrants," says Bhim Bahadur Khatri, a horticulturist with the Potato Research Program at the National Agriculture Research Centre (NARC) in Khumaltar. "Potatoes in the Valley probably arrived via Patna."

Other potato researchers will tell you that more than anything else, the introduction of the potato into the Himalaya, had a massive impact on the population growth in the region. "Like in Europe," says Dr. Alejandro Camino, a Peruvian academic with the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), "the root crop produced a population explosion." The introduction of potatoes to the highlands allowed communities to move higher, and also stay through the winter in their high-altitude homes.  This, in a way, is exactly why the Potato Research Program was set up in 1991, to increase the production of potato to feed a rapidly growing population. It produces clean seeds through tissue culture, educates farmers to improve traditional seed practice, and is even experimenting with growing potatoes from the seeds of the flower and not the tuber, as is traditionally done. Every year, the centre distributes 200,000 disease-free seeds germinated in its laboratory. "This may be peanuts considering the demand. But these are good quality seeds and it's the initial first step to flush out the use of degenerated seeds," says Khatri.

This, in a way, is exactly why the Potato Research Program was set up in 1991, to increase the production of potato to feed a rapidly growing population. It produces clean seeds through tissue culture, educates farmers to improve traditional seed practice, and is even experimenting with growing potatoes from the seeds of the flower and not the tuber, as is traditionally done. Every year, the centre distributes 200,000 disease-free seeds germinated in its laboratory. "This may be peanuts considering the demand. But these are good quality seeds and it's the initial first step to flush out the use of degenerated seeds," says Khatri.

After rice, maize and wheat, potato production in Nepal is fourth in terms of area coverage. In terms of productivity, however, the miracle tuber is first in terms of production per unit area. But we have some catching up to do-Nepal could grow 125 tons per hectare, it manages less than a tenth of that.

Things have changed beyond belief in the last 20 years. "Until 15 years ago, there were some Nepalis who had never eaten potatoes, but on the whole, now, much of Nepal has some sort of potato diet. It's one of the few crops that can be grown the year round," says Bhairab Risal, a communications expert. In the 1980s Risal was involved in a Swiss project (the Swiss helped promote potatoes in Nepal as early as 1960) to motivate Nepali farmers in the mid-hills and high hills of Nepal to store standard potato seeds in rustic stores at 6,000 ft. "It meant that Nepali farmers wouldn't have to rely on potato seeds entering from neighbouring India," says Risal "The culture among Nepali farmers has always been to use the good produce for their own consumption and store the okay ones for seed. This increases the probability of a bad crop." Degenerative seeds from India and Nepal's not-so-strict quarantine rules also affected Nepal's potato yield. The project did was build rustic stores across the country, in Ilam, Letang in Morang, Sunsari and Panchthar in the east, Dolakha in the centre, Kaski and Surkhet in the western and middle west development regions, and taught farmers to store quality seeds to ensure a next generation of fine potatoes. Most of these attempts have borne fruit that is visible till today.

The Potato Research Program currently recommends six varieties of spuds for Nepal. That may seem like nothing compared with the 4,000-odd strains that the Peru-based International Potato Centre classified there, but then the potato is intertwined with the very origins of Peru. Legend has it that when the first Inca ruler Manco Cap?c and his wife Mama Ocllo emerged from Lake Tititica to found the Inca empire, the first thing the god Wirachocha taught them was to plants potato fields.

Aloo ko achar

Ingredients

Ingredients

? pound potatoes

? cup sesame seeds

? teaspoon fenugreek seeds

? teaspoon turmeric

? teaspoon salt

? teaspoon chilli powder

2 tablespoon mustard oil

Juice from 2 lemons or

? teaspoon chook or

1 teaspoon mango powder

Boil the potatoes. Peel and cut each into eight pieces. Roast sesame seeds lightly in a pan without using any grease until they start to pop, then grind them in a blender. Mix potatoes, sesame powder, salt and chilli powder. Squeeze the lemons into this mixture. Heat the mustard oil in a small pan and fry fenugreek seeds until they blacken, then fry the turmeric. Add to the potato mixture with a very small quantity of water.

Time required: 15-50 minutes

Serves: Four-six persons

Sukhe aloo

Ingredients

Ingredients

1 pound potatoes

3 tablespoons butter

1 onion

? teaspoon turmeric

? tablespoon coriander leaves chopped

? teaspoon cumin seed

salt to taste

pinch of chilli

Wash, peel and quarter potatoes. Heat butter and brown onion. Add cumin, turmeric, coriander, and potatoes. Mix well and fry for ten minutes on low heat, stirring frequently. Cook till potatoes are done, adding salt and chilli 10 minutes before they are cooked through.

Time required: 35-40 minutes

Serves: Two-four persons

Aloo Raita

Ingredients

Ingredients

2 cups yoghurt

2 big potatoes

? cup tomatoes sliced

? cup teaspoon cumin seeds (dry fry and powder)

? cup teaspoon salt

pinch of black pepper

pinch of chilli pepper

1 tablespoon chopped coriander leaves

Boil potatoes, peel and cut into fine pieces. Mix with tomatoes. Beat yoghurt smooth, add cumin powder, salt and pepper. Fold into tomatoes and potatoes. Garnish with chilli powder and coriander leaves.

Time required: Five minutes

Serves: Four persons

From The Joys of Nepalese Cooking

POTATOE

"I had heard, before my visit to Nepaul, that our most esteemed kitchen vegetables did not only grow there in much higher perfection than in Bengal, but that the propagation of them was annually continued from their own seed, whereas the short duration of our cold season admits but of a scanty and degenerate produce not to be depended upon. My disappointment, therefore, was very great on finding the fact otherwise, and on being assured that they could not raise even potatoes, without procuring every year from Patna fresh roots for sowing; I think it extremely probable, however, that their failure in this respect has been occasioned solely by want of attention or skill, having no doubt, for my own part, that with proper management, there are few of our hortulan productions, whether fruit, flower, or herb, which might not be successfully reared, and abundantly multiplied, either in the valley of Nepaul itself, or in one or other of the numerous situations adjacent to it. The only kitchen vegetables we met with here were cabbages and peas, both of which were of the worst kind. They have the Tibet turnip, but cannot raise it, any more than the potatoe, without renewing the seed annually."

Colonel Kirkpatrick in An Account of the Kingdom of Nepaul, A Mission to that Country in the Year 1793.