2003

The beginning of 2003 was marked by a ceasefire agreement between the government and the Maoists on 29 January. But it was short-lived and collapsed on 27 August following three rounds of failed peace talks. The country went back to violence, and journalist Gyanendra Khadka was beheaded in Sindhupalchok. Young children were used as pawns with private school shutdowns as well as kidnapping and murders. Subsequently, more and more people were fleeing for the comparative safety of Kathmandu, adding to the capital’s unsustainable urban sprawl.

While the war waged in the countryside, Kathmandu was becoming unlivable in other ways. The quality of air was worsening by the day. The Supreme Court banned vehicles older than 20 years from plying, but that was not the answer. A page 1 headline ‘Gasp’ on issue #137 drew attention to the unbreathable air. Twenty-two years later, things have changed -- but for the worse.

We doubled down on the crisis with another spread ‘Breathing is Harmful to Health’ on issue #155 where environmentalist Bhushan Tuladhar looked into how the concentration of particulate matter from newly set up monitoring stations showed that people were breathing air with pollutants several times higher than the WHO standard. The main culprit: vehicular emission made worse by adulterated fuel, and soot particles from the brick kilns.

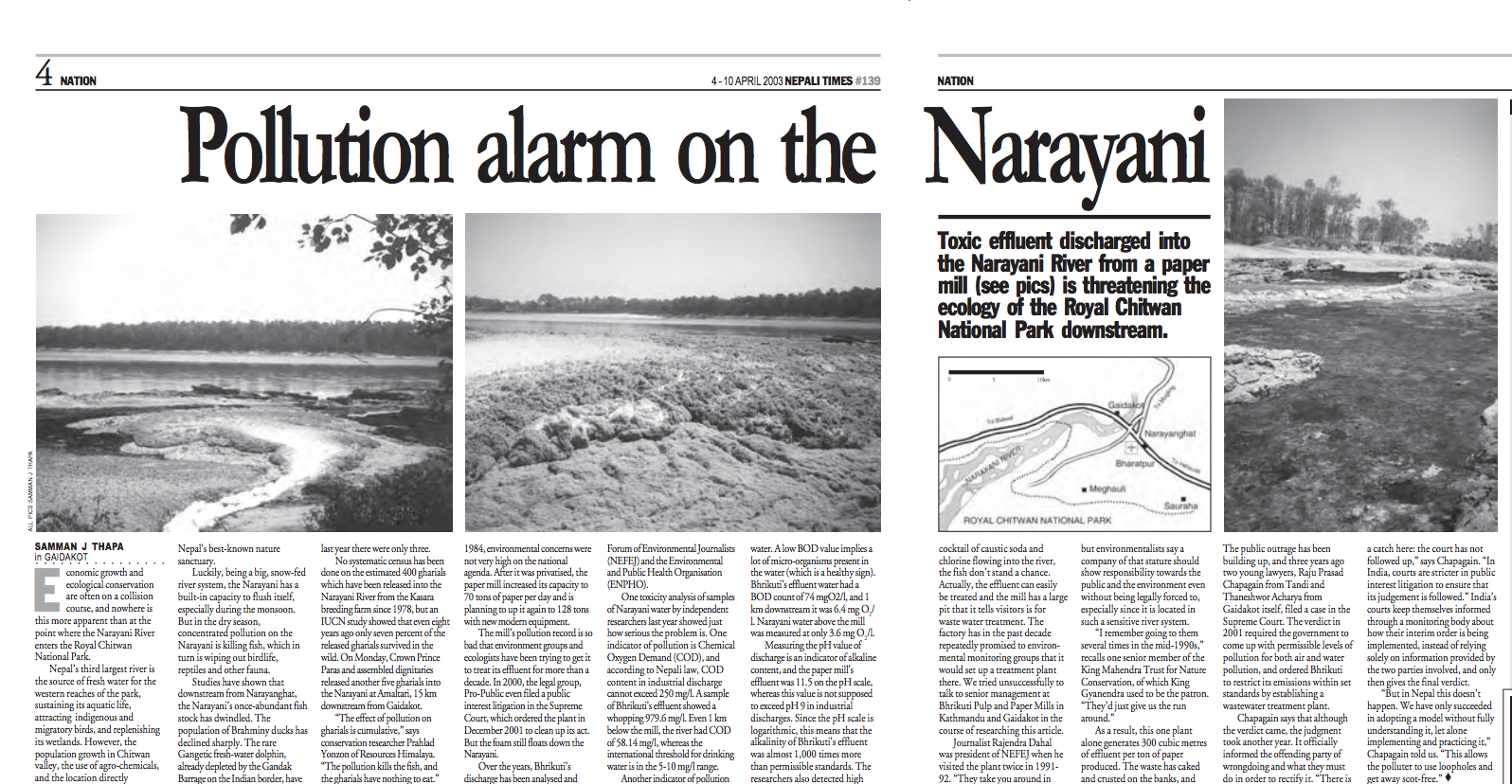

That year we also exposed toxic effluent being discharged into the Narayani River by a paper mill, threatening the ecology of Chitwan National Park downstream. The investigation showed toxicity analyses of Narayani water:

‘One indicator of pollution is Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), and according to Nepali law, COD content in industrial discharge cannot exceed 250 mg/l. A sample of Bhrikuti’s effluent showed a whopping 979.6 mg/l…’

Measuring the pH value of discharge is an indicator of alkaline content, and the paper mill’s effluent was 11.5 on the pH scale, whereas this value is not supposed to exceed pH 9 in industrial discharges. Since the pH scale is logarithmic, this means that the alkalinity of Bhrikuti’s effluent was almost 1,000 times more than permissible standards. The researchers also detected high concentrations of ammonium nitrate and nitrite.’

Back in 2003 we were already reporting on a ban on Nepali women going to work in the Gulf following the death by suicide of Kani Sherpa who was sexually abused by her employer in Qatar. We said the restriction was a serious violation of freedom of mobility, livelihood and self-determination rights, especially as the ban was arbitrary and implemented haphazardly at Kathmandu airport.

Interestingly, in issue #156, Shiva Gaule exposed Kathmandu airport for being a global centre for human trafficking:

‘Kathmandu airport is not just where Nepalis use fake documents to get out of their country, it is also getting the reputation among the international human smuggling networks as an easy airport to transit. Our lax controls, immigration desks with inadequate counte rfeit detection equipment, rampant corruption, and a huge domestic demand for fake travel documents from Nepalis desperate to migrate for a better life make it an ideal jump-off point.’