Post-pandemic mental health epidemic

The number of Nepalis suffering from mental health issues is increasing with the prolonged COVID-19 lockdown, and the lack of treatment and counselling means the country may be facing an epidemic of psychosocial disorders.

Mental health is a hidden pre-existing crisis in Nepal because of social stigma, with a survey three years ago showing that a shocking 37% of the population suffered from some form of mental health problem.

But a new survey this month shows that the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown to contain the contagion has exacerbated the problem, with a quarter of those surveyed saying they felt restless, fearful, anxious, worried all the time.

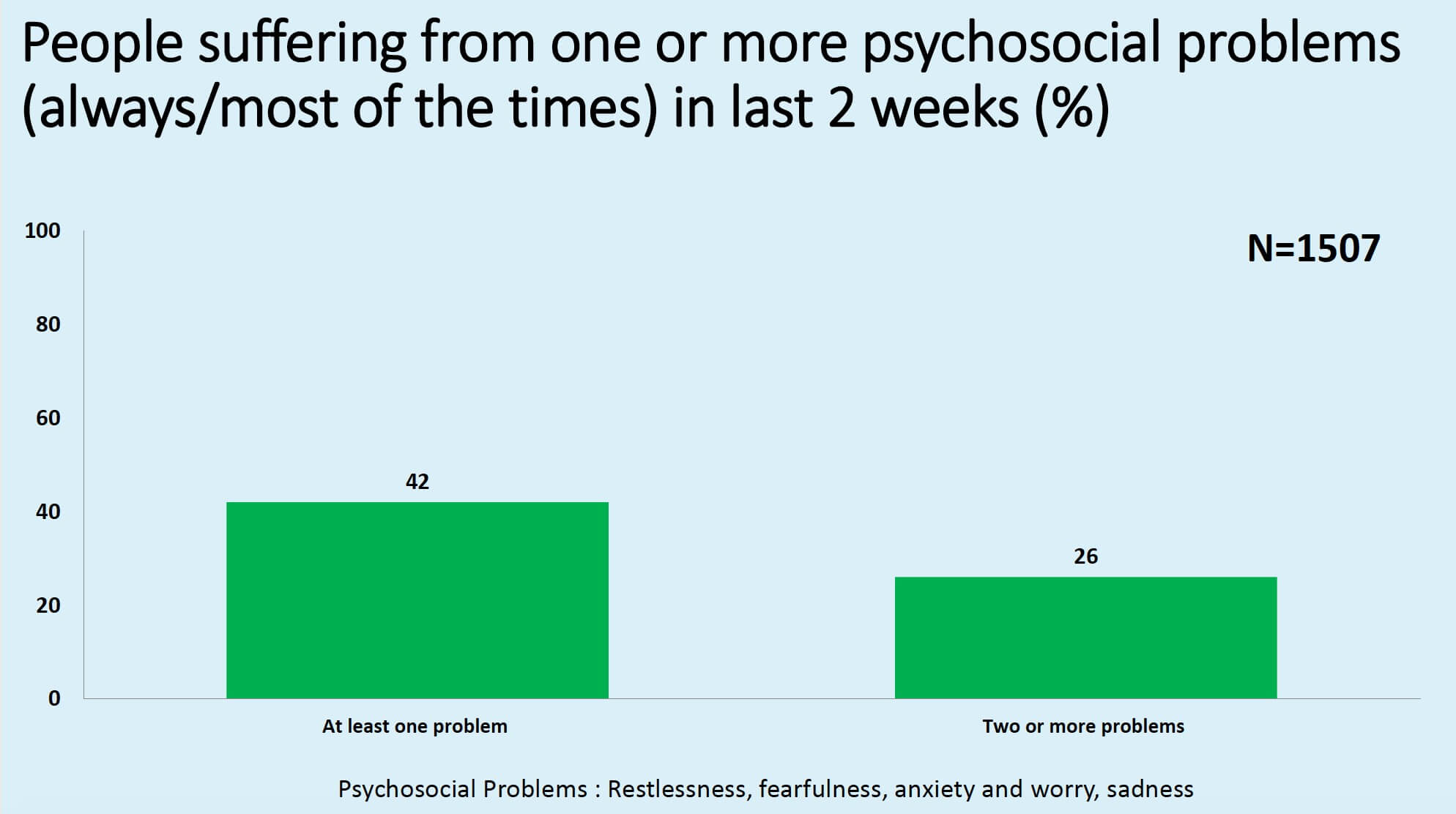

42% suffered from at least one kind of psychosocial problem, and 26% from two or more. At least 15% of respondents admitted they had taken to alcohol and substance abuse.

Over 1,500 Nepalis participated in the survey by Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation (TPO) Nepal and Sharecast Initiative during the lockdown, which has now lasted a month.

“The fact that 25% of those surveyed admitted to experiencing constant psychosocial problems due to the COVID-19 pandemic is a significant finding,” said Kamal Gautam, psychologist at TPO Nepal. He explained that problems were more frequent among women, students stressed about postponed exams, people whose businesses are impacted by the lockdown, and daily-wage earners.

The findings could be a warning about an impending epidemic of psychiatric problems as the lockdown and its impact is felt across society. In fact, mental healthcare providers say they are already seeing more patients with depression and anxiety disorder, as well as more severe psychoses.

A 21-year-old boy was recently admitted to Patan Hospital for psychotic breakdown after he started throwing things around his house, and screaming that everyone was going to die from the coronavirus. Also last week, a girl who had taken to excessive cannabis use during the lockdown was brought in due to serious side effects.

“A lot of people are suffering silently, unable to come to us due to the lockdown and it is very likely many do not recognise the symptoms of mental disorder,” said Raju Shakya, professor of psychiatry at the Patan Academy of Health Sciences. “It is normal to be worried during the time of a pandemic, and most people can cope with it. But some experience persistent symptoms of mental health disorder, and prolonged stress can also lead to self-harm.”

Alcohol consumption as a coping mechanism adds to existing mental and physiological problems, as well as lead to an increase in domestic abuse. Alcohol relapse is among the most common cases during the lockdown at Patan Hospital.

For mental health counsellors this is a vivid reminder of the mental health crisis following the earthquake five years ago this week. A survey of earthquake-affected districts of Rasuwa, Nuwakot and Makwanpur by TPO Nepal in 2017 showed that nearly 40% of respondents suffered from depression and anxiety for a year-and-half after the earthquake. Another 22% said they had suicidal thoughts, and a quarter had taken to drinking heavily.

“We are going to see a huge surge in mental health cases once the lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic is over. We have to get our limited facilities prepared to handle the situation,” Shakya predicted.

Mita Rana, a clinical psychologist at Teaching Hospital agreed that service providers will be overwhelmed with old and new patients if the lockdown is expended. She said many of her patients with pre-existing mental health disorders have not been able to come for follow-up consultations or get medications.

“During a time of a disaster or an epidemic, anxiety disorder, phobia, obsessive compulsive tendencies and depressive thoughts are more likely to be triggered in mentally-ill people and aggravate their condition,” Rana explained.

Although children tend to be generally spared by the virus, they quite easily pick up anxiety from their parents and relatives. Health care workers, migrant workers and their families are among the most vulnerable to mental health breakdowns because they often face stigma and discrimination from neighbours and relatives.

Mental health care providers including hospitals, clinics and non-profits have started a tele-mental health program during the lockdown. TPO Nepal alone has responded to 126 calls in the last three weeks through a toll-free number. Others have set up social media platforms, and 24/7-consultation services.

Nepal’s second confirmed coronavirus patient Prasiddhi Shrestha, wrote in her blog this week following a successful recovery: ‘One thing I have grown to realise in this process is that often times we disregard the mental health part of the virus. Symptoms like shortness of breath are largely capable of exacerbating one’s anxiety as well as the ignorance the public may show towards them.’

TPO Nepal:

Toll-free number: 16600102005

Centre for Mental Health and Counselling Nepal

Toll-free: 16600185080, Hotline: 1145

writer

Sonia Awale is the Editor of Nepali Times where she also serves as the health, science and environment correspondent. She has extensively covered the climate crisis, disaster preparedness, development and public health -- looking at their political and economic interlinkages. Sonia is a graduate of public health, and has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Hong Kong.