Things eventually work out

A Nepali migrant in Australia who fundraised for the victims of the GenZ protests finally able to release money to families amidst personal crisisThis is the 75th episode of Diaspora Diaries, a Nepali Times series in collaboration with Migration Lab providing a platform to share experiences of living, working and studying abroad.

My father was a country boy from Sarlahi, and my mother a city girl from Kathmandu. They had an inter-ethnic marriage, which was difficult until the two families gradually began to accept it.

My parents, who worked in development, viewed the world through a social lens. They often traveled overseas for their INGO work, leaving me and my sister behind. We spent a lot of time at my grandparents’ house, or in rented apartments with guardians.

Between Grades 1 and 10, I must have switched schools seven times. Our parents prioritised our education, and enrolled me in the most expensive schools. I was shocked by my school fees, and often wondered how they managed with their salaries.

I wanted to become a businessman, so I could have the kind of life some of my well-to-do friend had. My family was not from a business background, and social services didn’t lend themselves to that kind of lifestyle. Now I realise what my parents gave me was already over the top, a truth that becomes clearer as I get older.

Our family was getting along fine until our father died while working on a project in Dhading in September 2021. The official reason was ‘heart attack’. We do not talk about this much, perhaps as a way of dealing with the loss.

He was our rock, and everything got harder. At least we had good people around us who reminded us to take care of our mother and to work hard. And we did.

My sister and I made TikToks during the lockdown, initially in a joint account which reached its peak in 2022-2023. I had always wanted to be an actor, but I knew the film industry does not pay well. My parents also urged me to keep my interest in acting as a passion project.

TikTok enabled us to showcase our talent for comedy. We figured out how to crack TikTok’s algorithm and stayed on top of trends. People liked our duo and the raw and authentic content. It required a strategy, luck, planning, and understanding the game.

We use a hashtag #NakarmiKhanalAF in all our content drawing from my parents’ last names although they did not need to know what ‘AF’ stood for.

My first viral content involving a humorous take on a Marvel character hit over 500k. That fusion combining international trends with Nepali humor worked really well, and I started making it my niche, adapting content.

My father was always thick-skinned and did not have to try to be cool or tough. He was unapologetically himself, sometimes to the point where my sister and I felt embarrassed. When he was invited as a chief guest at a cricket game, for example, I remember feeling proud to be the child of an ‘important person’, but he grabbed the mic and told everyone to start cleaning the ground.

Many of our friends came from wealthy families because of the schools we attended, and he proudly lectured them about our humble background and the importance of social service.

Growing up, we tried hard to get his validity. My proudest moment was gifting him a shirt bought with my first salary. My father did not get to see our rise on social media, but I know he is watching over us just as he always did.

The first brand deal I got was memorable but awkward. It was for a grooming package for private parts. I used to think about how movie actors start their journeys with advertisements for underwear, and this was going to be my story, my ‘humble beginning’ as a content creator.

They did not even pay me money but just gave me the items. Other brands started coming in and with them, money. I earned as much as Rs40,000 per content and tried to make one every day. This was a big contrast to my monthly salary of Rs35,000 in a clothing store.

All along, I was acutely aware that fame would not last forever. Just like one of my singer friends Wangden had said in a podcast: he was going to have fun while fame lasted.

After TikTok was banned in India, there was even more uncertainty about social media. The alternates were also not assuring: people running businesses had to close up or were stuck, and the political uncertainty was scary. This pushed me to think about migrating, and Australia was a safe backup.

I uploaded content right upto two hours before my flight from Kathmandu. I wanted to have enough savings so I did not have to start working right away in Australia. I was buying freedom.

Since I had to change schools frequently, Rodin was one of few enduring friends I had. He was in Australia and assured me that he would take care of everything, and he did. He was my family there, and I did not have to go through the initial struggle that other international students had to endure.

In Australia, I have done multiple jobs over the last two years and completed my MBA. My interviewer challenged me to make him laugh with one of my content videos. He did and I started work the very next day though I know I got the job because a hardworking friend had recommended me. To the boss, I was just another Nepali who could work swiftly. I mopped floors, washed dishes, and served customers. This was Australia, and I hustled. But I knew there had to be more to life.

The long hours and little sleep eventually caught up with me. One day I slept 14–15 hours straight, and when I woke up, it hit me that I should try networking.

I reached out to admins of Australia-based Facebook groups. Some replied, some did not, some offered jobs that were not for me. Then came an email from 8848 Momo House, and I travelled to Brisbane to meet the owner Hom Pyashi.

“Do you want momos?” was the first thing he asked warmly. He told me to stop by one of his new outlets and make a video. I did, and I was hired the next day.

It was that easy, and I have been working there ever since. My boss would later share in a conversation that he did not hire me because of the video but because I was young and he saw hunger in my eyes. To him, I was clay that he could help shape.

I am now the marketing head, and the chain is doing well. Content creation is still a side job that brings in money. But just as my parents said, it remains a side passion.

Then came the GenZ protests. On social media I compared Nepal’s youth to relaxed backbenchers who finally act when provoked enough to get things done. I could relate to the rage and suffocation. A song I was featured in was supposed to be released just when social media was banned in Nepal, and that fuelled my anger.

But from the onset, I was wary of the headless nature of this movement, there was no ठुलो मान्छे leading and no one would be accountable if something went wrong. There was so much uncertainty, and I am not comfortable with uncertainty.

We were glued to social media as the protests happened, at work and in the gym. When we learnt of the deaths of young Nepalis back home, a part of me died. The grief of unexpectedly losing my father came back.

I left the gym early because I just could not take it. My friend and I just drove quietly to a nearby waterside. We did not even sit together because neither of us wanted to notice that we were in tears.

One of the messages I received was a GoFundMe link to support the victims. I shared it, but someone asked if it was genuine. That is when it hit me that I had a large social media following and could not just share things without verifying them. I removed the link.

The only person I felt I could trust was myself, so I decided to start my own fundraiser. I felt emotional and helpless, and had to do something.

I assumed we could raise around AUD5,000. I was wrong. Within hours, we had raised nearly AUD60,000. Fellow content creators Avash and Manzil from Minority Report had also started a GoFundMe, and we decided to join forces.

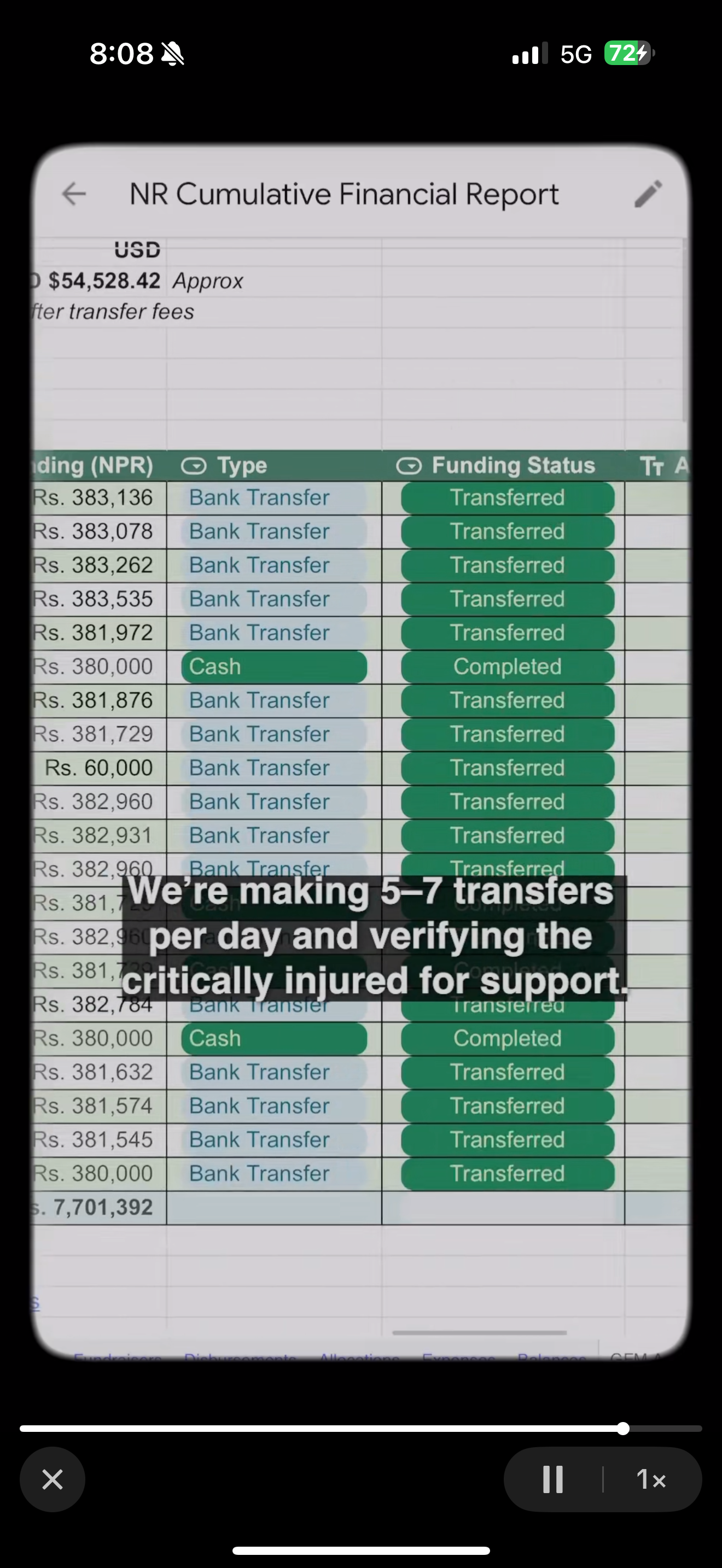

Partnering with them was going to be a lifesaver because I was not at all prepared for what was ahead. Over 11,000 people contributed across our two campaigns, raising AUD514,386.

But we had not thought through the logistical challenge, the online hate and the delays. We needed to release the money to the right organisations in Nepal, get complete information about the families of the martyrs and injured — our primary target groups.

We faced a huge amount of backlash after a hate narrative instigated by a few people spread online. We just could not get our message across that it was not as simple as raising the money and handing it over. People believed what they wanted to believe.

Internet hate can take you to very dark places, even when you believe in your cause and know it can bring some comfort to grieving families. You try to focus on the positive message, because many people did support us, but the hate and accusations do bring you down.

When I was paralysed by the internet hate to carry out even the most mundane activities like cooking and cleaning, my roommate Bibek took over. He even made me watch an episode from the Mahabharat capturing Krishna’s teachings on karma without worrying about the fruits, a lesson that did not just help me get out of that depressive episode but has become a guiding principle for life. How would I have emerged out of that darkness when I was battling with suicidal thoughts if people had not showed up for me?

We worked day and night to find the right partners, and because of the large amount of money and the level of transparency we asked for, many influencers or organisations turned us down.

This was not easy because we had our own jobs to take care of, our own bills to worry about that were not linked to the fundraiser. It helped that my team at 8848 let me deal with this during work hours, and assured me that they will stand by me no matter what.

Thankfully, we finally partnered with Nepal Rising (Daayitwa US), a professional and transparent organisation that stepped in and saved the day. GoFundme finally released the funds to their account and it has begun reaching the right people. My sister helped ensure the money is delivered properly.

As a final check, I speak with the families in Nepal and offer my condolences. I honour their loved one’s contribution to our country and we will make sure it is never forgotten. But no matter what we say or how much we try to help, the heartbreaking truth is that their young son or sibling is not coming back.

The narrative is slowly changing. Slaps are now claps. But the trauma of the public hate is so great that it still gnaws at me, I have anxiety about attending Nepali gatherings like concerts here.

I remember when a dance I had created for Bola Maya went viral on TikTok, with tens of thousands of people picking it up. A chef friend told me it was time to use that influence for a social cause. Those words stayed with me.

As I navigated the backlash, I was also reminded of my parents who worked on social causes and asked my mother if they had faced similar cases. She had, and she reminded me that all we can do is stay focused on the cause and drown out the noise. Things will eventually work out.