Buddhist relics in western Nepal

The secrets of a flourishing 1,000-year-old empire are just being revealed in Surkhet ValleyJust a 10-minute auto ride from the bustling city of Birendranagar in Surkhet, via a road that meanders through a lush green forest, a hillock marks an mystery — a medieval looking, six-metre tall, shikhar style temple surrounded by ruins.

Since its discovery about 50 years ago, the site Kakrebihar has piqued the interest of archaeologists and Buddhism scholars. They agree it dates from the 13th-14th centuries, but question if it is really a Buddhist site or a Hindu temple that adopted Buddhist features.

Is it one of many places along a route that passed through the Surkhet-Dang area in prehistoric times, bypassing the inhospitable Gangetic plains to the south? Who built it — followers of the Vajrayana Buddhism of the Kathmandu Valley or of the Tibetan Buddhism of the mountains? And was it even constructed as a temple, or could it have been a palace, monastery or something else?

Read also:

Lumbini is not a Buddhist Disneyland, Anil Chitrakar

Lumbini's unholy mess, Om Astha Rai

The discovery half a century ago of what seemed a lost Buddhist paradise in western Nepal, populated by Janjatis and Hindus, was intriguing. Buddhism had been virtually unknown outside of the Kathmandu Valley and Nepal’s mountains, and had even disappeared in Buddha’s birthplace Lumbini, which is today surrounded by Muslim settlements.

The Department of Archaeology (DoA) excavated the site in 2000, and has been working at it slowly over the past three years. Stone craftsmen work hard all day chiselling exact copies of broken pieces. The task is expected to be done this year, but the DoA’s decision to use concrete to join the stone pieces is controversial.

“The stone pieces were hard to put together, and concrete was the only viable option. We consulted with experts before we arrived at this decision, which is the best way to preserve the site,” says DoA Spokesperson Ram Prasad Kunwar.

Because the structure was made of stone, much of it has survived, though in fragments. Scattered at the site are stone walls, facades, statues, spires, wells and more, but there are few clues as to what these pieces originally looked like as a whole. However, they suggest an architecture similar to that of temples in Kumaon, which was once part of the Khas kingdom.

Read also:

Hidden treasure, Rupa Joshi

Sacred Survival, Michael Jordan

After excavation and a detailed study of the structure’s foundation, the DoA decided to piece the ruins together to make a shikhar style temple, which was also the dominant Kumauni style of that era.

The 12th to the 15th centuries marked the reign of Khas kings, rulers of a powerful kingdom that stretched from Trisuli in the east to Kumaon in the west, Tibet in the north and Bodhgaya to the south. Using the last names Challa and Malla, they ruled from their capital in Sinja, Jumla.

Evidence points to the Buddhist nature of this state: the fact that Sinja was a confluence of Buddhists from Tibet, Kashmir and Kathmandu, and that Buddhist kings of the Pal dynasty from Bengal had settled in Jumla. Buddhist scriptures gifted by Khas kings to shrines in Kathmandu still exist, and King Ripu Malla’s signature on the Ashok pillar in Lumbini can still be seen.

After this though, all at Kakrebihar is guesswork. There are no records to indicate who created the site. According to a signboard it was done by Ashok Challa around 1268 AD, but experts say it could have been built earlier by another king, Kraa Challa.

Statues of Buddha found at the site indicate that it was a Buddhist site, but the presence of Hindu deities like Ganesh, Saraswati and Shiva throws that thesis into question. Some see it as a Hindu-Buddhist shrine.

Read also:

Preserving Nepal’s soul, Stéphane Huët

The script of the scriptures, Sewa Bhattarai

The signboard at Kakrebihar proclaims that its builders followed Mahayana Buddhism, but the statues, as well as the Khas kingdom’s interactions with Vajrayanis from Kathmandu, Bengal and Tibet, indicate Vajrayana.

Conflicting theories also exist about the building’s destruction. Some suggest it was levelled by an earthquake in 1833, but Buddhism scholar Basanta Maharjan thinks it was destroyed by invading Muslim soldiers in the 14th century, before they were eventually defeated in Dailekh.

At most, the ruins of Kakrebihar offer tantalising clues to a mysterious past, which is being pieced together by craftsmen from Bhaktapur, who are tooling missing pieces for the temple.

The Karnali province chief minister Mahendra Bahadur Shahi recently announce plans to turn the area into an open zoo, while experts think it should be conserved and investigatged. Many say the DoA should be actively searching for other structures that surely exist at the site. “The site is randomly called Kakrebihar, but no bihar (monastery) has been found there yet. More excavation of this area is needed, which will lead to better understanding of Buddhism in western Nepal,” says Maharjan.

Why is the site in ruins?

The debris of Kakrebihar has inspired many stories. While these tales are at odds with historical facts, they show how the enchanting ruins have captured local imagination.

According to local Tharu folklore, the temple was a palace built for the Pandava princes, characters of the Hindu epic Mahabharata. They were supposed to be burnt alive in the palace of lac, but discovered the plans and fled, destroying the palace.

Another local folktale says that two sets of partners competed to build temples overnight. While the duo called Lati Koili managed to build a Shiva temple at the adjacent Lati Koili hill, the sali-bhena duo (brother-in-law and sister-in-law) found their temple still unfinished when the day broke. Ashamed, they destroyed whatever they had made and fled.

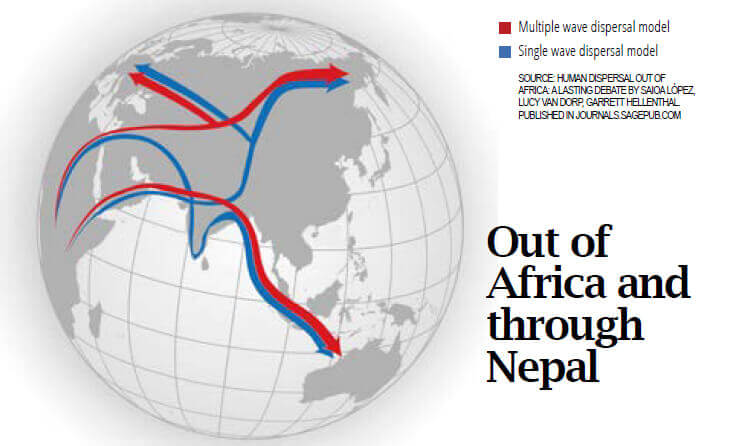

Paleontologists agree that humans moved out of Africa about 70,000 years ago, and spread out across the world. Several theories exist about their migration routes, and recent geentic studies of the Y-chromosome with samples taken from all over the world have helped figure out their historical movements. A popular theory suggests they first crossed over to Central Asia and eastwards to India, then Southeast Asia, with one branch walking on to Australia and another through the frozen Bering Strait to the Americas.

A study by German palaeontologist Gudrun Corvinus in 1984 published definitive evidence of prehistoric settlements in Nepal's mid-mountain region. 'The research has yielded an unexpected number of Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic sites and filled the lacuna of knowledge about prehistoric settlements in Nepal,' wrote Corvinus in a paper published in the journal Ancient Nepal in July 1985, which mentioned sites in Dang and Deukhuri with remains of hand-axe flakes, blades, adzes, core-scrapers and points.

For the first time, this proved that the entire belt of valleys at the foothills of the Chure, perhaps including Surkhet, was inhabited by prehistoric peoples. 'There is no question now that during the prehistoric times Nepal, too, was occupied by people who fashioned stone age tools and were able to penetrate through the thick forests of Terai,' writes Corvinus, adding that prehistoric people may have stopped by in western Nepal on their way to Europe via the Caucasus and eastwards. The relics in many parts of Nepal are similar to ones in Vietnam and Thailand, indicating that the Nepal Chure route was used by humans to travel to Southeast Asia, bypassing what at that time must have been dangerous jungles of the Gangetic plains.

Corvinus concludes that prehistoric people settled along the hospitable foothills of the Chure hills 12,000-30,000 years ago. But today, with soil erosion and changes in geography, it is increasingly difficult to find evidence as the prehistoric objects are first exposed and then washed away.

Read also: Prehistoric painting in Mustang, Sahina Shrestha