2020

The world before and after Covid-19 are two different realities. The pandemic was a Hollywood dystopian nightmare and changed how people live and work, what we eat, and how we travel, our social dynamics and technological leaps. It also exposed or, in some cases, aggravated pre-existing inequalities.

While the exact origin of the virus, which was first reported on a small scale in November 2019 from Wuhan remains contentious, Covid-19 was the latest in a long line of infections that jumped from animals to people, establishing the connection between new and emerging diseases with the relentless extraction of natural resources. It also widened the gap between the rich and poor countries.

Countries sealed their borders and locked their citizens in the confines of their homes, but they could not do the same to the novel coronavirus. The world is a global village, a wily virus detected in one part of the world rapidly spread to every known corner in a matter of days. It continues to this day with a new sub-variant of the Covid-19 being detected every couple of months.

After the shutdowns, the repatriation of Nepali migrant workers became a priority (right). They had lost their jobs in destination countries and had no way of coming back.

There were some Nepali embassies in West Asia which worked overtime to bring workers back home safely. Migrants from India walked for days only to be stopped at the border. Desperate, some even swam across the Mahakali River to get home.

Before long, hospitals were overflowing with patients and there were not enough supplies or staff. The Nepali diaspora sent home money in record numbers, they also flew equipment including medical supplies such as oxygen cylinders.

The poorest were the hardest hit. The lockdowns meant they had no source of income, and their health and nutrition were directly compromised. This was even more acute during the second wave caused by the more aggressive Delta variant. Even younger people were hospitalised, and the need for a vaccine, especially for the elderly and people with comorbidities, was at its peak.

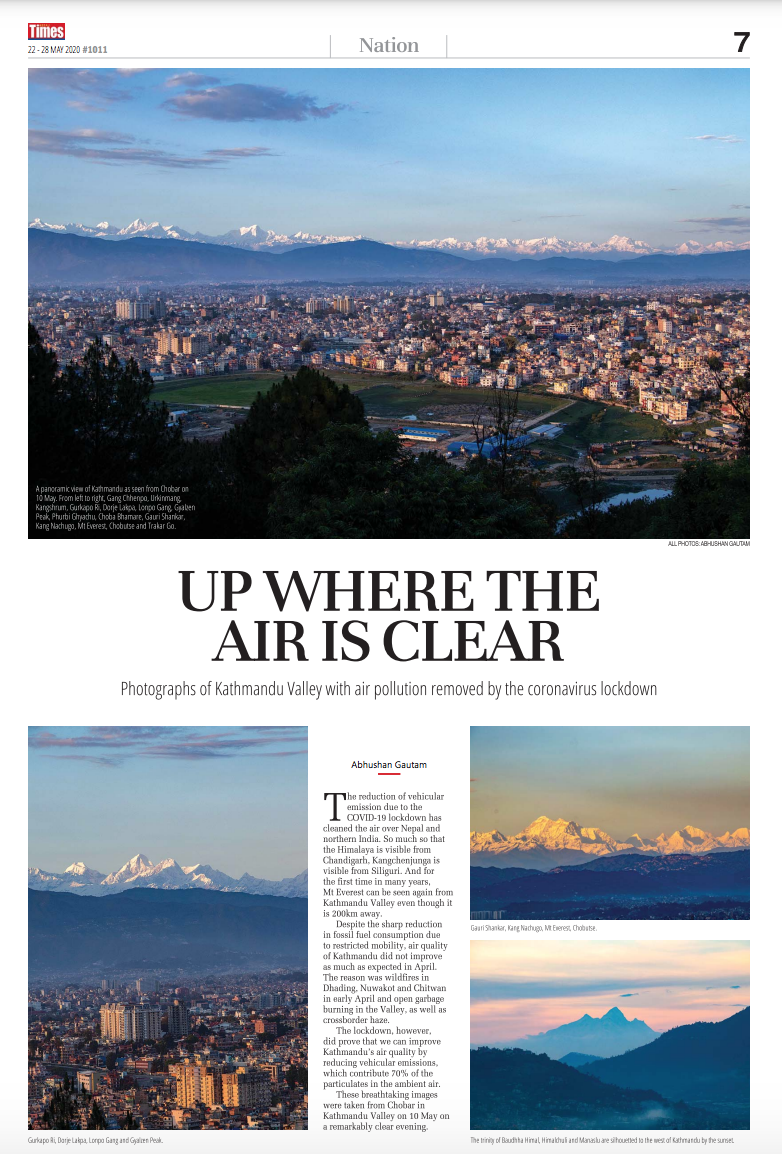

Improved hygiene and mask wearing saved many lives. With no vehicular or industrial pollution across the Subcontinent, Nepal’s air was clean again. Mt Everest was visible from Kathmandu, Abhushan Gautam’s iconic photograph was on Nepali Times #1011.

Vaccine diplomacy came into play. COVAX, a global vaccine initiative, was at least able to deliver the first batch of vials to the neediest, showing that multilateralism was still relevant. Even so, some are more equal than others.

Our very first coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic (pictured) by research scientist Sameer Mani Dixit was dated 29 January 2020, when the global death toll was at 213 and a little over 9,000 cases. By the end of the pandemic, it had claimed at least 7,010,681 lives.

Covid-19 has had other insidious impacts on society, ranging from undermining previous gains on public health and poverty to societal breakdown, mental health, and racism. The pandemic touched every corner of public and private life and reshaped the world.

Covid-19 also brought the world together. Never before had there been a quicker breakthrough in terms of vaccine development as countries with the most resources facilitated the process. Nepal became one of the biggest contributors to the Covid recovery trial which found that a cheap steroid dexamethasone was the most effective drug for the treatment of hospitalised Covid patients.

Just five years later, the world is more polarised than ever before, Covid is still lurking amidst vaccine denial in the US, people are more intolerant towards differences, countries are pouring money into wars and moving away from humanitarian causes.

We have forgotten how the pandemic turned the world upside down, and that it can happen again.