82 in २०८२

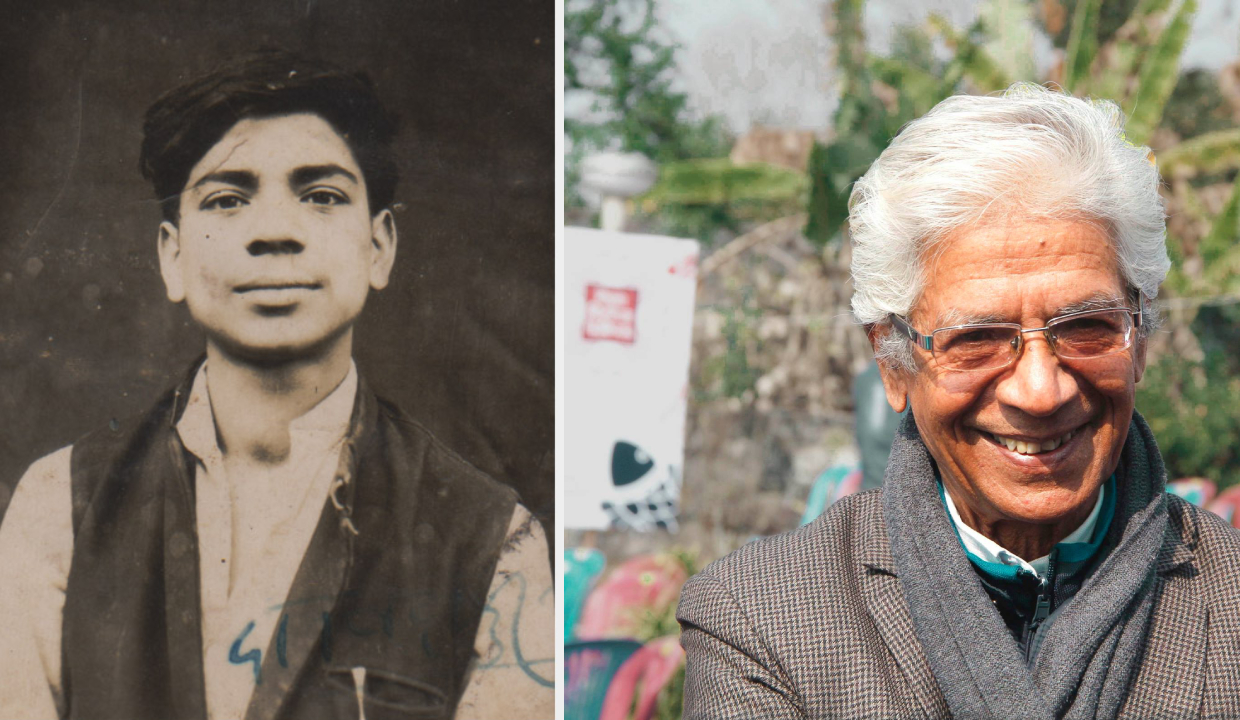

Nepalis born around Bikram Sambat year 2000 remember what life was like, and how it has changedDurga Baral

Artist and cartoonist, Pokhara

My actual birth date is in 1999BS, so I may not qualify for your selection of 82-year-old Nepalis. My earliest memory is of going from our home to our mother’s place crossing that rickety wooden bridge with bamboo handles across the Seti Gorge where the Mahendra Pul is today. I must have been about 6, and remember being really frightened.

Childhood in Pokhara in those days was heaven. Our home was small and thatch-roofed. Every house was surrounded by a garden of fruit trees and flowers. In spring, the air would be scented.

Of course, life was difficult, my grandmother had to wake up at 4 every morning to fetch a ufu|f] of water after waiting for 1 hour in line. But people were decent and happy, contended, satisfied with what we had.

Pokhara’s scenic setting, the mountains and lakes and its ethnic diversity made people here tolerant. We grew all the food we needed, and only had to rely on नुन, तेल, कपडा from the market.

Today, of course, everything is from the shops or imported. Everyone is in a hurry, no one has any time to sit back and if they do they are on their phones. People are stressed and have all kinds of worries. Things are not peaceful anymore in the country, either.

As an artist I have always been inspired by the sight of Annapurna and Machapuchre from my house. I have painted them so often that I know their shapes and texture by memory. But this winter, the sight of the back pyramid of Machapuchre was shocking. I have never seen it so devoid of snow.

But people are so busy running hither and tither, they do not even notice that the mountains are melting in front of their eyes due to climate change.

I took on the pen name Batsayan for my cartoons in which I used to lampoon leaders with elastic morals, the sycophants and hypocrites — and there were plenty of them after 1990. One of my cartoons after the 2005 coup was of a soldier escorting a underclad farmer carrying a Rolls Royce on his back into the royal palace. I think it has some relevance today.

But as the violence got worse during the conflict, I felt cartooning was not adequate to convey the national trauma. That is why I went back to painting the pain and suffering of war.

Pokhara perhaps because of its scenery has been an incubator of the arts. We are insulated from the shenanigans in Kathmandu, and have a different perspective.

As told to Kunda Dixit

---

Prakash Chandra Lohani

Former Finance Minister

I was brought up in a joint family. My grandfather had eight sons, and with their families, we were 45 people. My uncle was Nepal’s first physicist, my father an engineer.

The importance of education was thus impressed upon us at a young age.

After my studies in Nepal, I got a PhD in Economics in the United States, and returned around 1970. In the absence of institutional infrastructure in Nepal to accommodate the financial theories I had learnt I decided I could be more productive in politics.

I won a seat in the 1971 election under the Graduate Constituency which reserved four seats in the Rastriya Panchayat from a pool of around 10,000 university graduates across the country.

Nepal was changing rapidly. Access to education and information enabled Nepalis to question themselves, their role in and relationship with the state, and their connections to communities that were not their own.

This was also a time when people began to realise whom the state resources belong to, which helped establish Nepal’s budget and regulatory systems. King Mahendra had realised that the monarchy could not justify its leadership purely as the will of god.

The king set up administrative mechanisms and introduced many reformist policies. The Public Service Commission was launched, marking a move towards meritocracy. He also established the Planning Commission, and introduced land reforms. Nepal moved towards import substitute industrialisation.

We were also able to establish Nepal’s identity as an independent sovereign nation. During the Cold War we leveraged our relationships with the US, Soviet Union and China to get development aid into the country.

A society constrained for one-and-a-half centuries had been opened up to new ideas. As we moved towards a conventional Parliamentary system, emerging leaders, including politicians like me who had brought a new perspective through our overseas academic backgrounds, also played a role in Nepal’s socio-political evolution.

In 1980, King Birendra held a referendum on the nature of the political system that was most suitable for Nepal. A new legislature that enshrined the principle of one-man, one-vote was set up with substantial power vested in the monarchy. I was elected as a member of the new legislature from my home district in Nuwakot in the election held under the new Constitution, and was subsequently appointed Finance Minister.

At the time, there were only two state-owned banks in the country, and financial development was primitive. I felt that my first task was to reorganise the financial sector as an effective instrument for mobilising resources and investment through the private sector.

I was able to convince people that Nepal’s banking sector must be competitive to bring about innovation and productivity. I maintained that for the rapid development of the financial sector, Nepal should allow new banks collaborating with foreign financial institutions and investment, Nepali entrepreneurs, and the public.

During my term in office, I inaugurated the Nepal Arab Bank, now known as Nabil Bank, and the Nepal Indosuez Bank, now Nepal Investment Mega Bank. The Nepal Finance Company Act was promulgated to make space for Nepalis who did not fit the clientele of big banks. A new stock market was also established.

We also facilitated the Agriculture Development Bank to collect deposits from urban centres to invest in rural areas. In fact, I was the first to make a deposit. Ultimately those deposits ended up being spent on urban development instead, but that is another story.

This was Nepal’s silent banking revolution, in which I played a role. Today, the challenge is to direct available finance into sectors like manufacturing, agriculture, and small businesses.

As Minister for Housing and Physical Planning in 1988, we formed a road network plan, as well as a Kathmandu city urban development blueprint that would prohibit building along floodplains, green the embankments for flood control and ecological preservation.

Had we been able to put that plan in place, Kathmandu would have been far more liveable today. The encroachment into river banks is unfortunate, and it is still not too late to implement those plans. Sadly, that does not seem to be a priority at present.

As told to Shristi Karki

--

Rewati Rajbhandari

Author and Poet

Here I am having a conversation with Sudiksha about my memories of life and family. I have completed my second जंखु celebration. It has been indeed a wonderful 82 years.

I was very naughty as a kid, and my friends gave me the nickname ‘Caterpillar’. They used to tease me saying, “She’s a caterpillar, she doesn’t sit in one place and keeps moving from here to there.”

Me and my cousins were always creating a nuisance, jumping on haystacks and other mischief.

As soon as my periods started, my mother did not allow me to go to school despite my father insisting. I did not mind not being allowed to go to school, I was happy playing at home. I was very close to my grandaunt, she was the only person who could stop me from crying. It was difficult to come to terms with her death.

I was married off at an early age and had three sons, the youngest who was sickly died despite our efforts to save him. I was devastated, so much so that my husband was worried for me. Then, I started reading books voraciously and also writing poetry which I never published.

Then, one day an incident occurred that changed my life. My husband and I were walking past Bhote Bahal, which at the time was full of trees. I saw an abandoned baby girl and this tore my heart to pieces.

I asked my husband if we could adopt the baby, but he refused. I remember what he said to this day: “The person who abandoned this child is just like you because you also throw away the poems you write.”

That remark was an epiphany. From that day onwards, I never threw away any verse I wrote and started collecting them, aiming to have them published. I have to thank my husband for opening my eyes, he has played a great role in supporting and encouraging me. He was there with me through thick and thin till he passed away from cancer.

My first publication named खिचडी came out in 1988, and I dedicated my collection of poems to my mother. It was my mother who introduced me to poetry by chanting certain sloka and mantra, and she used to say the words in it were written by god. Her pronunciation was so pure that we could hear the sacred sounds and feel closer to the Almighty.

I must have inherited the genes for writing poetry from my mother. I just could not stop writing, and by now have 20 published works in Nepali and Newari with poetry, story collections, storybooks for children and my autobiography as well.

With age, my writing has slowed, but I still have a few collections to publish. I am planning to bring out a book in Newari soon and then get it translated and published in Nepali as well since the Nepali reading audience is much larger than that of Newari.

There are a lot of things I still want to write about. But, Sudiksha, one last message I would like to give to your younger readers is to keep reading and writing. If you want to be a writer, there is only one thing to do: write and keep writing, whenever you feel like it, wherever you are, and whatever is in your mind. And, oh yes, never throw away what you have written.

As told to Sudiksha Tuladhar

---

Bharat Koirala

2002 Ramon Magsaysay Awardee

As the youngest son in a middle class Nepali family of seven that moved from Gorkha to Kathmandu, I must have been quite pampered. It was a privileged upbringing, and I was one of the first students at the newly-opened St Xavier’s School at Godavari in 1957. The Jesuit education provided me exposure, ethical, moral and spiritual values.

After graduating, I attended morning college and worked as a tourist guide at the Royal Hotel run by Boris Lissenavitch. Later, I joined the press division at the British Embassy where, because I got to read the British newspapers, I became interested in journalism.

The government launched The Rising Nepal, and I joined as a reporter, profiling international visitors and accompanying King Birendra on official visits. There were not too many journalists fluent in English, and I heard that the newspaper was used in a well-known school as an example of how not to write English!

I also edited the Gorkhapatra for some years and in both papers my priority was in human interest stories about the lives of ordinary Nepalis. Trained journalists were in short supply, so I went on to help establish the Nepal Press Institute (NPI) and the Nepal Forum of Environmental Journalists (NEFEJ). We specialised in training reporters to write on development and environment. In 1995, after five years of constant lobbying with the government, NEFEJ with help from UNESCO, set up Nepal’s, and South Asia’s, first community broadcaster, Radio Sagarmatha.

In all my journalism, I maintained good relations with those in power in different regimes, but always kept a distance. Despite greed and power struggles, regime changes, conflict, political instability, Nepal has made progress.

One wonders how much further ahead we would have been if we had a better government. Some credit must go to some enlightened politicians. No matter which system of government Nepal had or who was in power, we have made socio-economic progress.

Being in the media, I had the privilege of spending time with King Birendra and we used to have long chats during his visits to different parts of the country. He was genuinely concerned about the welfare of Nepalis, and listened patiently to ordinary people, giving instructions to officials to follow up.

In my media career, I worked with letter press, offset, telex machines, computer typesetting, and now things are moving faster with the Internet, social media, algorithms and AI. With all the multimedia content, I am nostalgic for the time when we had to think twice before adding a photo to a story because we needed to make an expensive zinc block.

Technology itself is a double-edged sword. It is good or bad depending on how we use it. Parents, schools and societies working for the welfare of families and communities must work harder to teach young people the value of new technology, especially social media. They also need to inculcate moral, ethical and spiritual values that give their lives meaning.

The younger generation enjoys many privileges that we never had. But these are mainly materialistic comforts and physical changes, which usually come at the cost of the erosion of moral values. Today’s students need the exposure to think more about the environmental health of the planet, societal and individual wellbeing, and compassion towards all living things.

As told to Kunda Dixit

---

Shyam Badan Shrestha

Entrepreneur

I was born in Gau Bahal in Patan. I did not have a father growing up. And for that, my mother and I were regarded as inauspicious. Being poor was already a burden, but women without a man to protect or provide deepened the scorn.

I saw how society turned its face on us. I remember the weight of that gaze. I studied till Grade 6 in Patan then we had to move to Janakpur. I spent three years there, studying in a local school where I was the only girl in my class. People used to believe that educated girls would become wayward and a threat to society.

We used to wake up at 2AM to the sound of grain being ground in the dhikki and jato. Finishing household chores, we rushed to school. It was hard to adjust between languages.

At home, I was accustomed to speaking in Newari but classes were in Hindi, and the villagers spoke Maithili, and we also had to study Nepali. Back in Kathmandu, I juggled work and study.

At age 13, I made a decision to change the course of my life by getting a higher education. I must work hard and make something of this life. That conviction carried me through.

I went on to complete my Bachelor's in Education (BEd). I excelled in Nepali which is not my mother tongue, and for that I credit my teachers as well. I loved to teach myself, but grew disheartened by how politics snuck into everything, even the classroom.

So, I chose a new path. With 20 rupees in my hand, I bought thread and began crafting potheads, something unheard of in Nepal at the time. There was no one to guide me, but knot by knot I set up Nepal Knotcraft Centre in 1984.

Today, we see machine-made goods everywhere, but handmade crafts have a soul. They carry the warmth of the maker’s hands, the rhythm of tradition passed from mother to daughter. To me, handicraft is not just work, it is therapy. It is art. It is identity. All that we must preserve and pass on.

Today I see girls going to school and women working, speaking up, making their own decisions. Back then, women were not to be seen, let alone heard. They were married off, to cook, serve in-laws, raise children, and stay quiet.

I have lived through that silence, fought it, and now I watch as it slowly breaks, and for the better. Technology has also transformed our lives. In our time, only a few families had radios to which we would huddle around to catch a bit of music. And now? The world is in the palm of our hands.

I hope Nepal continues to embrace technology in a way that can strengthen our roots. We need research and innovation to preserve our culture and explore our land’s available resources for eco-friendly products and local industries to thrive.

And for our crafts, we must keep our hands moving so the heritage lives on for generations to come.

As told to Sangya Lamsal

---

Dhruba Chandra Gautam

Novelist

I have been writing for a long time. Seven decades now. I was drawn to writing from a young age. My brother was a writer as well. I grew up around words.

My first poem was published at age 16. Looking back, the writing was somewhat immature. I didn’t choose the best word, or get across an emotion the way I wanted to. It took another six years or so for my writing to gain maturity.

The subject matter that I write about has also changed. I used to write a lot about love at first. Then I wrote about relationships between two people, not necessarily romantic. I liked to see how individuals interact with each other.

Later, when the mood in the country turned revolutionary, it was reflected in my work as well as of other Nepali language writers. I read a lot: the Mahabharat and Swasthani. I read voraciously at the university libraries. Life is short and fleeting, and there is so much I haven’t read, even on my own bookshelf.

My favourite book would have to be the Mahabharat, mainly for how it lays the story out. It was one of the earliest books I read and to this day I still go back to it. I have read it in different languages and versions. They say that everything that happens in life happens in the Mahabharat, but there are things that happen in the Mahabharat that do not happen in life.

The Mahabharat describes how people were in the Kali Yuga -- they aged quicker, for example. This is also a Kali Yuga. People are slaves to their weaknesses. There have been different political regimes since 2000BS. But the way people live has remained largely the same.

For the people in power, ideals have become like a bag that is hung from a rope to be pointed at. But I am not a political person. Writers have to be honest, of course. They have to be true to their work, and ideally in the lived life as well. A writer better not be corrupt.

Technology has brought a change in how people live. People are indoors more often, watching TV or on phones. The computer came along in the 90s, but I have always just used a pen. The computer made writing easier and led to more of it, and I don’t know if that is a good or a bad thing.

My writing habits have changed too. When I was young, I used to write all the time, day and night. I could leave a story halfway done and come back later and finish it with ease. I used to wait for reasons to stop writing, but now I give myself excuses not to start. I tell myself that it is too cold to write, or too hot. I think some of that is because of my age. I have just been writing for so long.

The New Year 2082 is upon us. I think we should approach it with hope and optimism, as if it were a newborn. You always want a baby to grow up and do well, to do something new. Let us hope we all get what we need, and that this fog lifts.

As told to Vishad Raj Onta