All the men and women merely players

Nepal’s theatre business is not doing well financially, but you would not be able to tell here in the alleys of Teku, home to Kausi Theatre and the drama group Katha Ghera. Despite being hard up, new theatres are rolling out productions thick and fast.

It all started with Aarohan Gurukul, established by actor-director Sunil Pokharel three decades ago, which later became the first private theatre to stage plays with multiple performances. Besides Kausi, Kunja Theatre and Purano Ghar have recently sprung up in Kathmandu, and there are more than 150 theatre groups across the country including theatre halls in Jhapa, Pokhara and Morang.

Three drama groups are building theatres in Pokhara alone, and many institutes like Actor’s Studio and Shilpee in Kathmandu conduct classes.

Kathmandu hosts frequent theatre festivals: this month Nepal Academy’s Rang Utsav honoured 13th century Maithili playwright Jyotirishwar and Shilpee Theatre held its Tamang Drama Festival. Former theatre artists like Min Bahadur Bham, Dayahang Rai, Khagendra Lamichhane, Menuka Pradhan and Saugat Malla have even migrated from the stage to screen, starring in Nepali films.

“It is good to see so many youngsters in theatre who understand film, music, art, and even the connection between space and performance,” says senior playwright Abhi Subedi. “Their interest seems to be in re-interpreting history and depicting the inequalities and cruelties in society.”

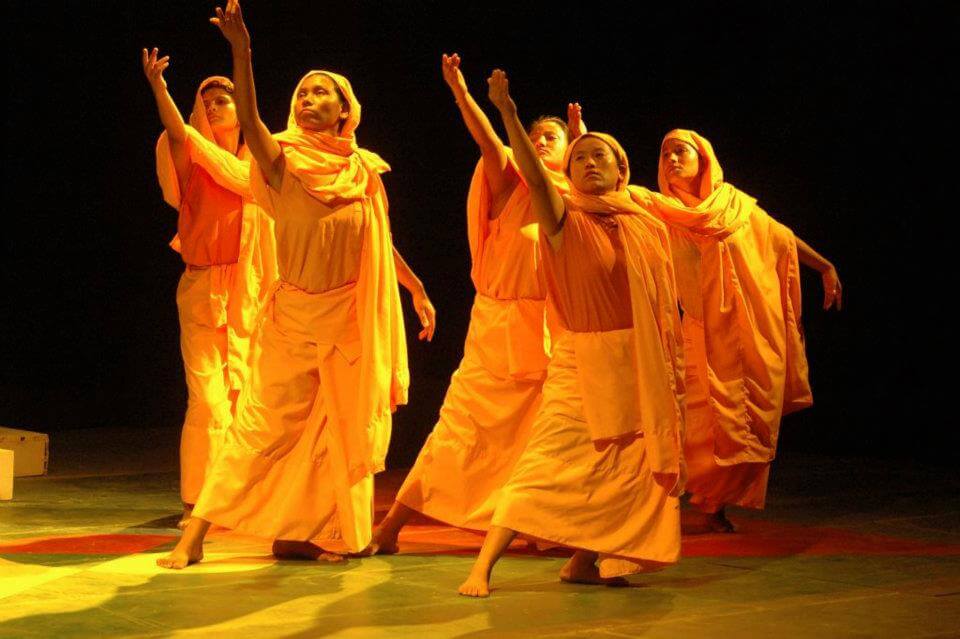

Recent plays like Court Martial questioned the caste system and hierarchy in the military. Harjeet reinterpreted a classic story from a woman protagonist’s perspective, Daraundi ko Pani imagined the life of Lakhan Thapa and Manakamana Devi, Bhrikuti portrayed Nepal’s famous princess who was married in Tibet, Ani Deurali Runcha depicted feudal oppression and forced migration, Jayamaya Afumatrai Lekhapani Aipugi enacted the journey of Burmese Nepalis fleeing World War II.

Nepali theatre has come of age, with plays that ask probing questions about social injustice, discrimination, and modern ethical dilemmas. Jiundo Akash portrays a transgender person, the adaptation of Vagina Monologues brought the private lives of women into the public sphere, while 30 Days of September sensitively tackled child abuse.

Despite these vibrant themes, however, Nepali theatre still struggles with originality. Few of the plays are new, and directors seem to prefer Shakespeare, Moliere, Tagore, or even Lu Sun to home-grown dramas. There is a general lack of technical knowledge of stage production.

“Nepali theatre lacks research, which is impeding its growth,“ explains pioneer theatre artist Sunil Pokharel of Aarohan Gurukul. “Different ethnic groups have diverse performance cultures in Nepal, we need to mine these cultures so that we can produce more original, Nepali-style plays.”

Strong folk performance cultures are evident in Janakpur, where Mithila Natyakala Parishad, one of the oldest theatre groups still active, draws from folk traditions and attracts big audiences to every performance. But it struggles with not having its own home stage.

Gurukul was one of the first to have its own theatre, but the hall was destroyed in 2012, followed by the closing of Theatre Village in 2016 and Theatre Mall in 2017. At ticket prices of Rs100-500, the income just does not justify the expensive land theatres are housed on.

Except for groups like Sarwanam, which has its own space, theatres rent and have to constantly worry about their future – which doesn’t do much for creativity. Dozens of groups have to take turns staging plays in the six or so threatres. Sunil Pokharel limits himself to just two plays a year because of space constraints.

“Theatre’s main problem today is that it lacks institutional support,” says Abhi Subedi. “There is no degree course on theatre in Nepal’s universities, and little government financial support to produce plays.” Pokharel says corporate sponsorship would do the trick and make up for the shortfall in ticket revenue, but there isn’t much of that.

Despite difficulties, artists find Nepal’s close, intimate theatres, where the audience can hear the performers breathe on stage very impactful. Says Pokharel: “There is no such thing as enough money, in any profession. And if you think you want to take to the stage, you have to be prepared to survive the harsh reality of theatre.”

Read also:

Real life drama, Abha Eli Phoboo

Bhagvad Gita as opera, Smriti Basnet

The theatre of life, CK Lal

A Midsummer Night's Sapana, Sahina Shrestha