Nepal’s Tharu are tiger protectors

On World Tiger Day, a tribute to the indigenous people who have traditionally protected the habitat of the tigerEvery year, up to 15 people are killed by tigers in and around Nepal’s Chitwan National Park, famous for its conservation success story.

But this was not always the case — elders say there used to be many more tigers but fewer deaths. What changed?

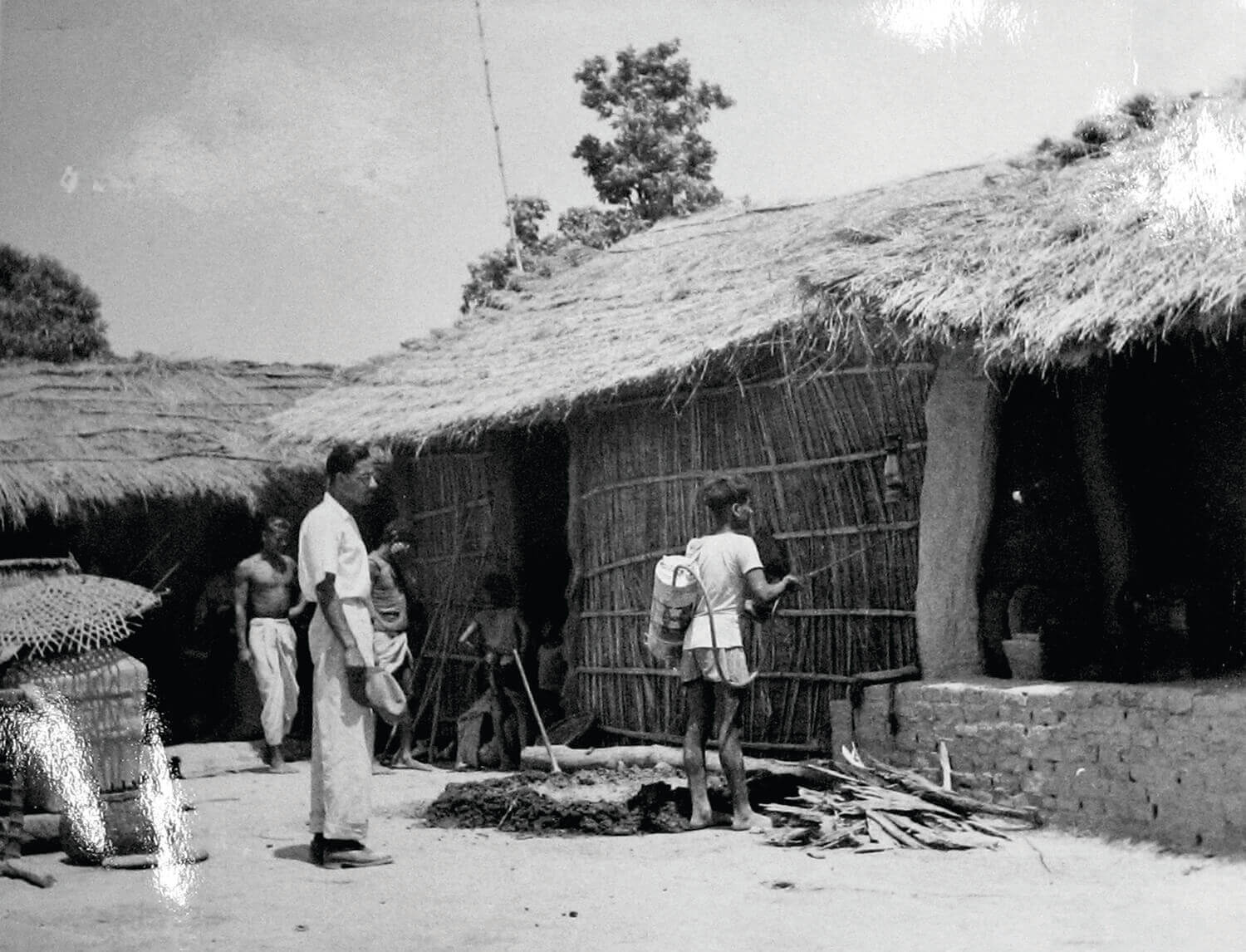

Long before Chitwan National Park was established in 1972, the indigenous Tharu people and tigers coexisted, fostering a centuries-old relationship based on an understanding of each other’s behaviour.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Tarai plains, especially Chitwan, gained fame for tiger hunting and proved useful as Nepal’s rulers employed hunting diplomacy by inviting British royals to extravagant hunting parties.

Hunting expeditions would descend from Kathmandu in winter months to avoid malarial summers. The Tharu supplied rice, vegetables, goats, and constructed access roads.

Rana rulers also relied upon Tharu mahout expertise in handling elephants, navigating the jungle, and tracking wildlife for hunting.

The Ranas and their guests killed an astonishing number of tigers. During a hunting expedition in 1850, Rana Prime Minister Jung Bahadur Rana personally shot dead 31 tigers. In 1876, during two weeks, British King Albert Edward VII shot 23 tigers.

In 1911 King George V killed four bears, eight one-horned rhinoceroses, and 39 tigers. Rana Prime Minister Juddha Shumsher is said to have killed 433 tigers from all across the Tarai between 1930 to 1940.

At the time, 90% of Chitwan’s population were indigenous Tharu, Bote, Musahar, with the Kumal making up the rest. While people were worried about their crops and food sources, they were also mindful of tigers, rhinos, and other forms of wildlife.

The Tharu trapped tiger prey such as wild boar and deer for their survival, also understood that predators like tigers sometimes hunted their buffalos, goats, and cows — especially when they grazed in or near the jungle. To Tharu, this seemed only fair.

“In 1973, just before the establishment of the Chitwan National Park, my family owned between 200 and 300 cows, oxen, and buffaloes,” says Keval Chaudhary, 95. “Tigers killed four to five of my cattle each year, but we never hated tigers and never felt like killing them. It was coexistence — we shared the same land.”

Shukhlal Chaudhary of Bachauli once told us there used to be significantly more tigers before malaria eradication in the 1950s, but that did not mean there was more conflict with humans.

“We used to go into the forest every day, and were familiar with the routines of the animals that lived there,” he used to say. “The tigers rarely ventured into our village or killed anyone who lived there.”

In the days before the National Park, the tiger population in Chitwan was probably bigger. The Ranas had laws against hurting rhinos and tigers, but more importantly, the Tharu also cared for the animals and the jungle.

This respect for nature runs deep in our tradition. The Tharu worship through the Gurau spiritual healer and honour the forest deity known as Bandevi.

Says Aasha Ram Mahato, an 85-year-old resident of Madi: “हमरा पुजा करइ खुनिय जम्मा देवी देउता जससनेकी सोमेसोरबाणि, कल्की माइ, बिक्रम बाबा सब थारु देवी देउता क नाउ लेके हमरा सन्सारी बर्ना कर्साहु इय जेठवा नत एसार्ह महिनावमा हमरा इअ बाली बिर्ही बचावके, बनवका चिजुवा बिजुवा बचावके कहके हमरा बरसमा ३ चोटी पुजा कर्साहु एसार्ही बर्ना, लेरुवा पैठ हसे चैत पैठ बर्ना।”

The Tharu take the names of all the gods they worship — such as Somesor Baani, Kalki Maai, and Bikram Baba, and perform Sansaari Puja, a traditional ritual to protect crops, wild and domestic animals, insects, and everything in nature.

This ritual reflects the community’s deep respect and spiritual bond with the natural world and is performed three times a year.

Bikram Mahato, 65, recalls an incident six years ago when 10 people entered Chitwan National Park to cut fodder grass. A tiger was 50m away, silently watching them and preparing to attack. The group quickly decided not to run or scatter. Instead, they stayed close together.

This smart and immediate decision prevented a tiger attack. It also depicts the Tharu indigenous community’s understanding of nature and wildlife, as well as their choice of coexistence and protection.

The Nepal government and foreign aid organisations have mostly forgotten the history of Tharu–tiger coexistence and the community’s silent but crucial role in tiger conservation.

Nevertheless, let us hope that the state will eventually acknowledge and pay tribute to the contributions of the Indigenous Tharu in protecting the forests and wildlife, especially the tigers, that currently make up Chitwan National Park.

Birendra Mahato is an elected member of the Ratnanagar Municipality Ward 6 and Founder Chair of the Tharu Culture Museum Research Centre in Sauraha.