Early Nepal drawings come full circle

For decades, Franz Frei’s drawings used for adult literacy classes in Dolakha sat in his late mother’s attic in Switzerland. Now 43 years later, the former Swiss Development Cooperation employee has brought the drawings back to Nepal.

As students, Ulrich Burtscher, Thomas Türtscher and Raimund Wulz made meticulous colour-coded architectural drawings of Ghyaru village in Manang, detailing their elevation, water supply, building use and shop density. After 30 years, the trio has returned to Nepal the sectional drawings of the slope and scale of the buildings and their relationships to each other, along with sketches and photographs.

After decades of being scattered across Europe, such archival material that provide valuable insight into Nepal’s culture is being brought back by former researchers and students. This return of knowledge is an initiative of Niels Gutschow, an architectural historian and adviser at the Saraf Foundation, who himself worked at the Bhaktapur Development Project in the 1980s.

It was Gutschow who convinced Frei to dust off the metal canister he had custom-made in Patan to carry his original drawings when he left Nepal in 1977. The zinc cylinder, which resembles a time capsule, is now in the Taragaon Museum with its decades-old baggage tag of Swissair and the drawings still intact. The canister is spot-lit at the centre of Frei’s exhibited works, surrounded by the artefacts it held in safekeeping for over 40 years.

“How many chickens do you see?” When asked this in 1976, villagers responded, “One”. Frei then realised that the ovoid blob on the far right of the chart was not a chicken but an abstraction of a 3D reality into a perspective -- a concept introduced to Europe in the 15th century. Frei learnt from these mistakes and took pains to avoid repeating such miscommunication.

The Saraf Foundation is working to procure, exhibit, archive and digitise such research material of foreign artists, photographers, architects and anthropologists who worked in Nepal in the second half of the 20th century.

Frei came to Nepal in 1976 as staff of the Swiss-funded Integrated Hill Development Project in Dandapakhar village of Dolakha, to conduct adult literacy classes for Tamangs in the area. He made black ink sketches to illustrate Devnagari words, but soon realised the villagers did not ‘see’ images in a way Western experts took for granted. Lines in the pictures and perspective reduction were not understood, and Frei’s sketches were utterly confusing to his grown-up students, some of whom looked at them upside-down.

This reminds Frei of the story of how pygmies from dense Congolese rainforest, when brought to the open savanna in Kenya mistook a distant herd of buffaloes for insects. Having never looked that far before, the vast depth of field that people in the plains took for granted was magic to the pygmy – as they approached the buffalo, the ‘insects’ grew bigger and bigger.

Similarly, a malaria prevention initiative projected images of mosquitoes on the wall to illustrate to villagers how the disease is transmitted. After the slideshow, the people were glad they would never be afflicted with malaria because “we don’t have such big mosquitoes here”.

Frei uses the anecdotes to critique his own work in Nepal, and how he found out how pictorial literacy is learnt. Later, he started using stylised depictions of everyday objects using the drawing techniques of local thangka painters as reference.

In Manang, architecture students Burtscher, Türtscher and Wulz had no common language to communicate with the Manang-pa with only a compass and tape measure drew the physical environment. Nearly 30 years later, they are valuable records of the ‘anonymous architecture’ of a Manang village before tourists and the road arrived.

Gutschow had to use all his powers of persuasion to get Burtscher to part with his drawings and bring them back to Nepal. Eventually, recognising how their work has developed a cultural significance, the trio agreed to surrender their drawings for safekeeping – admittedly keeping their favourites.

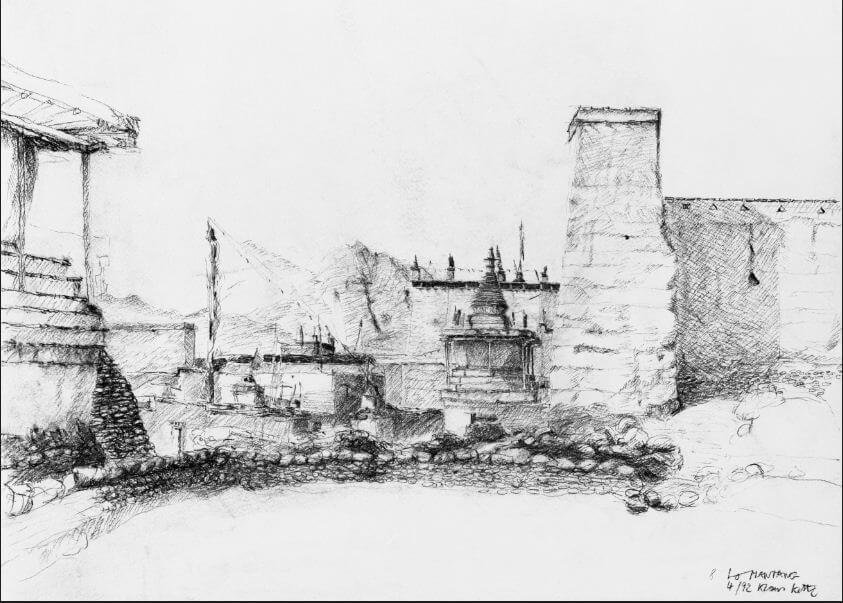

Klaus Kette worked on several survey missions in Mustang as an artist and his work is striking, allowing visitors to grasp the feeling of a place, recognition of a face, even if the lines that make the impressions are imprecise, gnarly whirls of movement. We journey through city streets, stop at landmarks, experience unknown interiors, survey remote landscapes, and come face to face with strangers.

In Kette’s swirling hand, in the Austrian trio’s maps, or in Frei’s Dolakha drawings we see what we know. Beyond that, when our eyes open there is magic and wonder. These young scholars depicted a hidden world – and whether we see it as magic depends on the rules and lines of perception behind our own ways of seeing.

At the very least, the works have come home.

The Taragaon Museum Lecture Series-7 Exhibition

Till 14 November at Taragaon Museum