Nepalis are having fewer babies. Why?

Family-friendly policies prioritising women and youth to sustain fertility ratesThis week at the National Population Policy launch Prime Minister K P Oli exhorted Nepalis to get married by age 20 and have three babies by the time they are 30.

This was the first indication that the highest office in the land has understood the need to address Nepal’s dramatically falling birth rate, but Oli’s statement was greeted with ridicule on social media — especially by women.

Most urban young are already grappling with economic pressures and shifting life priorities. Even with a university degree, many cannot find jobs, and are taking the first flight out for overseas employment. Having a child is now a fraught decision shaped by income, individual autonomy, and family pressure.

The UNFPA’s State of the World Population report released last month, highlighted a significant decline in fertility rates around the world. The global average fertility rate is 2.25 children per woman, and 18% of the reproductive adults said they will not be able to have the number of children they desire.

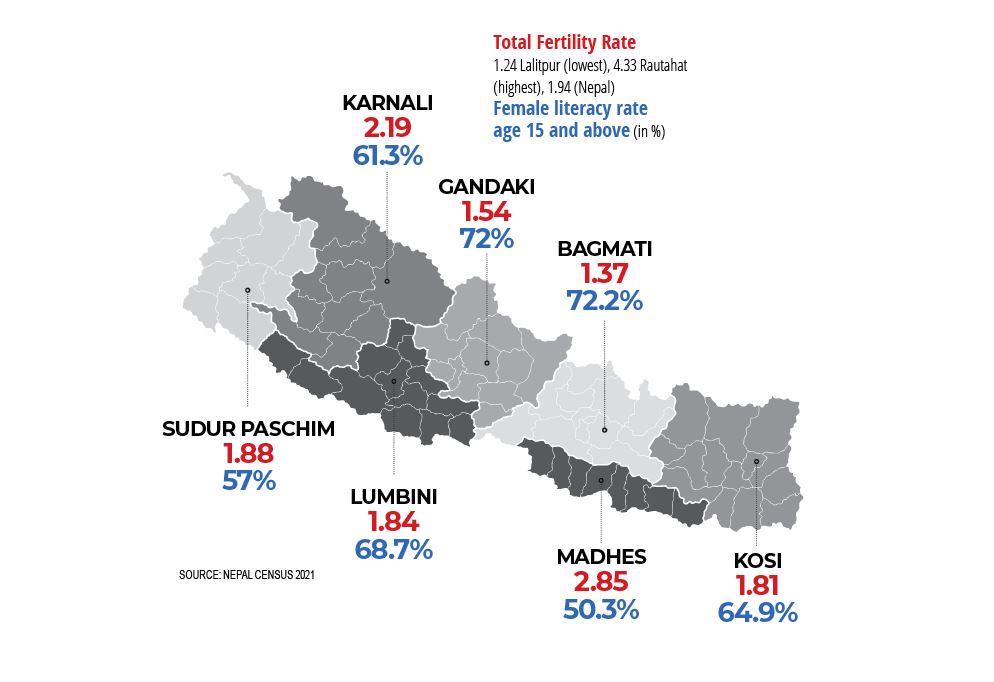

The total fertility rate in Nepal has plummeted to 2.1 births per woman — down from 5 just 30 years ago. This is considered replacement level, meaning the newborns will replace their parents.

However, birth rates are not declining as rapidly everywhere. The Tarai in has a total fertility rate of 2.20, and northwestern mountains is still 2.24.

There are multiple factors in play, and the report broadly divides them into four categories: health issues, economic concerns, fears about the future, and lack of a supportive partner or their absence. More than half of the respondents said finance, which includes unemployment and increased cost of housing, as well as parenthood, was a barrier to having children.

“More and more people prefer one or two children at maximum. Many women also decide to have children at a much later age,” says Kamala Devi Lamichhane of Tribhuvan University. “The opportunity cost is far higher for women.”

But there is also a cost for the country, as the National Population Policy notes. At the rate the total fertility rate is falling it will soon be below replacement level — meaning that in the next three decades Nepal will be confronted with an ageing population.

Besides income, there are also cultural factors at play in women having fewer babies — they are expected to do all the childcare duties, even putting their careers on hold. In general, there is little help from spouses, and with more nuclear families there is less support from relatives.

“Women today are well educated, career-oriented, and economically independent, allowing them to delay marriage as well as being conscious about their body and reproductive rights,” says Laxmi Tamang of the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM).

Also present at the policy launch was demographer Yagya Bahadur Karki, who said that women are more educated and hence, empowered to take their own informed decisions regarding having children.

He adds, “But the fertility rates have reached replacement rate, and that stands as a warning for the future.”

Fertility rates have fallen in inverse proportion to the rise in female literacy. The regions of Nepal where couples have more babies is where women are less educated. Couples in Madhes and Sudur Paschim provinces, where child marriage, gender-based discrimination, menstrual huts and dowry are still widespread are where the fertility rate is still high.

And because female literacy also has a direct correlation with infant and child mortality, couples in those regions tend to have more babies so some of them survive.

But it is Nepal’s urban centres among the educated where the increased choices in reproductive health, including alternative methods of conception like IVF and treatment for infertility, as well as contraceptives offer more options for family planning.

“There are more choices regarding reproductive health, and there is more awareness as well, which is why people decide carefully on whether or not to bear a child,” says population expert Yogendra Gurung.

Migration is another factor adding to the decline in fertility rates. Many young Nepalis of reproductive age leave every day in pursuit of better jobs overseas. Spousal separation means fewer children.

“Once away, even if not educated, they realise that child-rearing costs are high, and try to have fewer and even no children in some cases,” Gurung adds.

Recent studies have also shown that men returning after their stint in the Gulf and Malaysia, where they are exposed to extreme heat for extended periods as well as various chemicals and toxins in their work environment have a range of health problems, including infertility.

To increase the birth rate, Nepal will have to reverse its family planning strategy of the past 40 years. Complicating this is that some regions of Nepal will need measures to control the birth rate, while urban areas will need a strategy to help parents have more babies.

One way to help families have more children is to develop more family-friendly policies that favour women and youth as the Nordic countries, which also have falling birth rates, have done. They have introduced flexible parental leaves for both parents, including financial and health incentives.

China, also concerned about its declining birth rate and an ageing population, now has a three-child policy as well as tax deductions, expanded childcare services, and leave policies to encourage couples to have more children.

“We must work towards childbirth and childcare policies and plans that are suitable for Nepal, so that couples planning for children do not have to think twice about it because of finances or other reasons,” adds Gurung.

Tamang of the International Confederation of Midwives says a gender transformative approach is needed to address the issues of the gender gap which is adding to the decline in childbirth. Husbands need to play a more important role in child-rearing.

Instead of increasing fertility for the sake of it, the objective should be to assist young people to start the families they desire, at a point and time of their choice. Respect for everyone’s rights and dignity lays a foundation for a more balanced demographic trend.

Lamichhane sums it up: “If fertility rates are to be sustained, it requires changes in the gender roles and behaviour, keeping the youth’s aspirations in mind.”