The homecoming of Nepal’s gods

Nearly 40 years after it was stolen from Patan, a rare stone statue of Laxmi-Narayan is finally landing at Kathmandu airport this week, raising hopes for the return of thousands of other religious objects from Nepal.

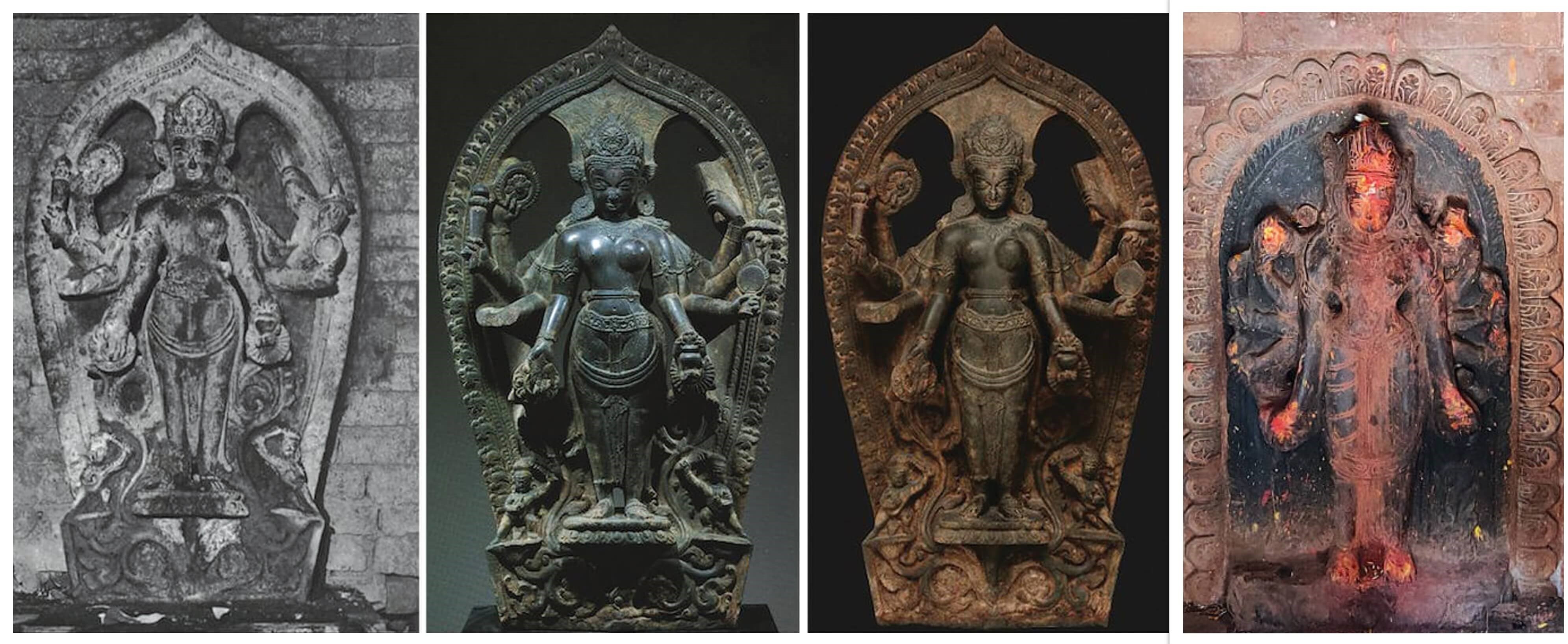

The 800-year-old androgynous idol was wrenched out of its shrine in July 1984 from Patan’s Pakto Tole where it was being worshipped till the day it was stolen. The figure surfaced briefly in 1990 at a Sotheby’s auction, disappeared again, and was later spotted at the Dallas Museum of Art where it was an ‘exhibit’ since 2007.

The US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) handed over the statue to the Nepal Embassy in Washington on 6 March, and it took some time for the documents to be processed and the transport costs to be raised, before the gods could finally be returned to Nepal.

“The deity will now be handed over to the Patan Museum, and we are preparing all the needed logistics here before it can be restored to its original temple,” says Damodar Gautam, Director-General of the Department of Archaeology.

US museum returns stolen Nepal god, Alisha Sijapati

Locals had made a replica of the statue that they worshipped after the original was stolen and installed it in the original place. Other religious objects that have been returned to Nepal have also been sent to the Patan Museum for safe-keeping so they will not be stolen again.

The process for the deity to be restored to its original space is lengthy. Community members have to reach out to the District Office in Lalitpur for paperwork for security purposes. While the bureaucratic wheels grind on, priests at Pakto Tole are already working to set an auspicious date for the special chamma puja reinstatement of the idol.

“When we bring back our God, there will be a celebration and a procession so that the world knows and understands that items from our living heritage is not to be stored and exhibited in their museums or private collections,” says Chiribabu Maharjan, Mayor of Lalitpur Metropolitan City.

Return of the gods, Sujata Tuladhar

Although overjoyed by the Laxmi-Narayan homecoming, community members are in a dilemma about what to do with the replica they have been worshipping since 1993.

Dilendra Shrestha, a board member of Patan Museum and himself from Patko Tole, says, “Even if it's a replica, it is still our god, and we will make arrangements to house both our gods.”

Shrestha says that for cultural and religious reasons, the original Laxmi-Narayan may not be kept as the central god anymore, as one of its hands was broken during transportation across the world. Gods that are damaged cannot be kept as the central idol in the temple even though they are worshipped, according to local belief.

“Most likely, both the original and replica will be kept next to one another, however, the decision will be made by the community,” Shrestha says.

Replicating Nepal's stolen gods, Alisha Sijapati

A photograph of the 15th-century deity was first published in Images of Nepal, a 1984 book by Indian historian Krishna Deva. Later, it was included by Nepal’s art historian Lain Singh Bangdel in his book Stolen Images of Nepal.

The collective effort of bringing Laxmi-Narayan home has set a remarkable precedent in repatriating stolen gods of Nepal, and has been a collective effort of historians, academics, activists, investigation agencies and the government of Nepal and the United States.

American artist Joy Lynn Davis who has documented stolen religious objects through her art is glad the Laxmi-Narayan is back to where it belongs. She had painted the Patko shrine with the missing deity depicted in gold.

“The day the Laxmi Narayan arrives in Nepal, I will be the happiest person—so many people and organisations have worked on this. The only way to protect them is to increase awareness about their significance. We have a lot of work to do, Laxmi-Narayan is just the beginning,” Davis told this paper earlier this year.

Indeed, an investigation by the Nepali Times tracked another deity stolen from Gahiti in Patan in the 1960s to the Denver Art Museum.

That figure of Uma-Maheswar has been cited in several books by art historians, including The Art of Nepal by Pratapaditya Pal in 1974, Stella Kramrish’s Manifestations of Shiva, Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1981, Krishna Deva’s Images of Nepal in 1984 and most notably, in Lain Singh Bangdel’s book Stolen Images of Nepal in 1987.

According to its website, the Denver Art Museum has mentioned the ‘known’ provenance of this Uma-Maheswar idol dating back to 1968 from Sundaram Works of Art and Handicrafts in India, till it acquired the statue in 1980 as a gift from the private collection of Jane F Ullman and Edwin F Ullman.

Nepal's gods return from exile, Alisha Sijapati

Sanukaji Maharjan, now 80, recalls how the deity had been stolen in the 1960s, was found and stolen again from Patan’s Bhandarkhal Garden.

“The first time it was stolen we fixed the statue firmly to the wall so that thieves couldn’t take it away again, but we were wrong,” says Maharjan. Since it was stolen 60 years ago, he is one of few people in Patan who remember the statue and its importance to the community.

"I am already in my 50s and the statue was stolen even before I was born. With time, the Uma-Maheswar has been more like a bedtime story for us, and we will do our best and work on giving it a permanent space in its home,” says Dinesh Maharjan of the Gahiti Tole Committee.

Slok Gyawali, founder of Nepal Pride Project based in Portland, Oregon who has worked persistently on repatriating the Uma-Maheswar, has been in touch with the Denver Art Museum.

In one e-mail exchange acquired by Nepali Times, the Museum wrote: ‘We continue to have confidence in the propriety of the provenance of the piece. Though we had been aware of the Stolen Images of Nepal publication, we are unaware of any substantiated claims of theft of this piece; indeed, other publications discuss the piece without reference to a theft.’

Gyawali then got in touch with 90-year-old Ted Ullman, scion of Jane and Edwin Ullman. He told Gyawali that his parents are not to blame, and after hearing from the Denver Art Museum he will be happy to write a letter of support for Nepal's efforts to repatriate this and other religion objects from Asia.

However, the 90-year-old in another e-mail wrote, "I remain very conflicted and have decided that I should not bring this up with the Museum which has already made their policy clear to me."

The Nepal Embassy in Washington DC told Nepali Times it is in touch ‘informally’ with the Denver Art Museum. It added that the Department of Archaeology had finished its forensic archaeological report and submitted it to the Ministry of Culture. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Kathmandu is waiting for the report to begin official correspondence with the Denver museum.

Back where they belong, Bhrikuti Rai

After the Laxmi-Narayan that arrived in Kathmandu this week was handed over to the Nepal Embassy in Washington last month, the Manhattan’s District Attorney’s Office transferred three other artifacts to the Nepal Consulate in New York: a 13th century carved temple eave depicting an Apsara, a 14th century gold seated Buddha in Bhumisparsa Mudra, and a 15th century seated Ganesh.

The District Attorney Office said the repatriation was part of its ongoing effort to return stolen and looted antiquities seized from the illicit collection of Subhash Kapoor, who was arrested in 2012. Along with heritage activists, Nepal government agencies are also stepping up efforts to bring back the stolen gods from museums and private collectors all over the world.

Lost Arts of Nepal in its Facebook page published two statues from Nepal that are in possession of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (‘The Met’) in New York. They include a 9th century ‘Shiva in Himalayan Abode with Ascetics’ which was originally a part of Kankeswori Temple at Shobha Bhagwati in Kathmandu, and a 16th century Goddess Nrityadevi originally from I-baha bahi in Patan.

Bringing our gods home, Sahina Shrestha

The religious objects appear to have been stolen so long ago that people in those neighbourhoods have no recollection of the gods that once resided in their temples.

‘Since The Met previously has sent two statues back to Nepal voluntarily, I am confident they can do the same this time too,’ the anonymous Facebook page admin of Lost Arts of Nepal wrote back in response to a Nepali Times query. Activists who have reached The Met have been told that the museum’s legal team is investigating the matter.

These images can be found mentioned in Lain Singh Bangdel's Inventory of Stone Sculptures of the Kathmandu Valley and Mary Slusser's Arts and Images of Nepal.

There are indications that the repatriation of Nepal’s stolen statues will now gather pace. Government officials say the Art Institute of Chicago has said it is ready to return an 8th-century Chaturmukhi Shivalinga on 16 April.