Waste not, want not

Government policies to drive recycling are crucial for electrical and electronic waste management in NepalA New York Times report this week on Nepal’s electric vehicle boom was widely shared. The world is finally taking notice of the country’s energy transition.

But the success story also brings new problems. Nepal will soon be facing a crisis in managing the lithium-ion of battery-powered cars, scooters and three-wheelers. Then there are mobile phone batteries, heavy metals and rare earths.

“It used to be just laptops and mobiles, so people didn’t care so much, but one electric car can mean up to 500kg of waste, it will be beyond our control once they start piling up,” warns Pankaj Panjiyar of Doko Recyclers, an electrical and electronic waste management company in Kathmandu.

He adds: “We were on track to generate 3,500 tons of lithium battery waste a year after 2027, but given the increased market of EVs the actual figure will now be much bigger.”

Besides lithium, there are also heavy metals such as cobalt, nickel, and manganese that can contaminate the air, soil, and water, as well as rare earths. Nepal imported nearly 1.9 million mobile phones in the past year, a 40% growth from the previous — and that was only through official channels. With 76% of new car sales being fully battery-powered, Nepal is second only to Norway.

Lithium-ion battery waste from electric cars, mobile phones, toys, solar panels and the 9,000 telecommunication towers all over the country already makes up a sizeable chunk of electronic waste.

Recycling lithium-ion batteries is possible but expensive, while the recovery rate of heavy metals, including gold, is at 95% or more. China is leading the game with more than half of the global recycling capacity of heavy metals at about 500,000 metric tons a year, much ahead of the United States and Europe.

Nepal does not have recycling infrastructure for lithium-ion batteries. In fact, there is no recycling plant for lead-acid batteries either: the acid is usually just dumped while lead, other metals and plastic are extracted by the informal sector or sent to India.

“Battery recycling is textbook engineering, it is not difficult, we should be able to do it ourselves,” energy economist Dipak Gyawali told a recent climate discussion. “But when there is no market, the standard law of political economy is that the state has to create one, that is how it happened in the US, the UK and China.”

Doko Recyclers had tried to set up a recycling infrastructure for lithium-ion batteries, and had nearly got a Rs40 million investment from Singapore-based Total Environment Solutions (TES). But Nepal’s lack of e-waste policy and investment guidelines meant the company was not assured of a return on investment and pulled out.

Nepal also does not have Extended Producer’s Responsibility (EPR), wherein manufacturers and distributors are responsible for disposal and pay for the recycling of the waste generated by their product, including batteries.

“It is only a matter of technology transfer when it comes to lithium-ion recycling, but it requires investment backed by government policies such as EPR,” explains Panjiyar. “But there must also be provisions for extracted raw materials like lithium. We don’t manufacture batteries in Nepal, so we have to export them. But who is going to pay for that?”

Lithium, heavy metals and rare earths also draw much criticism for unethical mining and environmental cost. One ton of mined lithium emits nearly 15 tons of CO2. Lithium is either extracted from briny water or hard rock minerals, add is often associated with contamination of water as well as loss of water sources. Nickel and cobalt mining comes with massive ecological cost and labour exploitation.

Sodium-ion batteries which are a safer, cheaper and more sustainable alternative. Battery-powered transportation could also be just a stepping stone to green hydrogen fuel of the future.

“If we are using these metals, at the very least deploy them for the benefit of the larger public, like by promoting electric buses,” says Shilshila Acharys of Avni Center for Sustainability which recycles plastic and other waste. “Ultimately, it comes down to our consumption patterns. It is much easier to use one less mobile phone or a car which wasn’t even necessary, than recycling.”

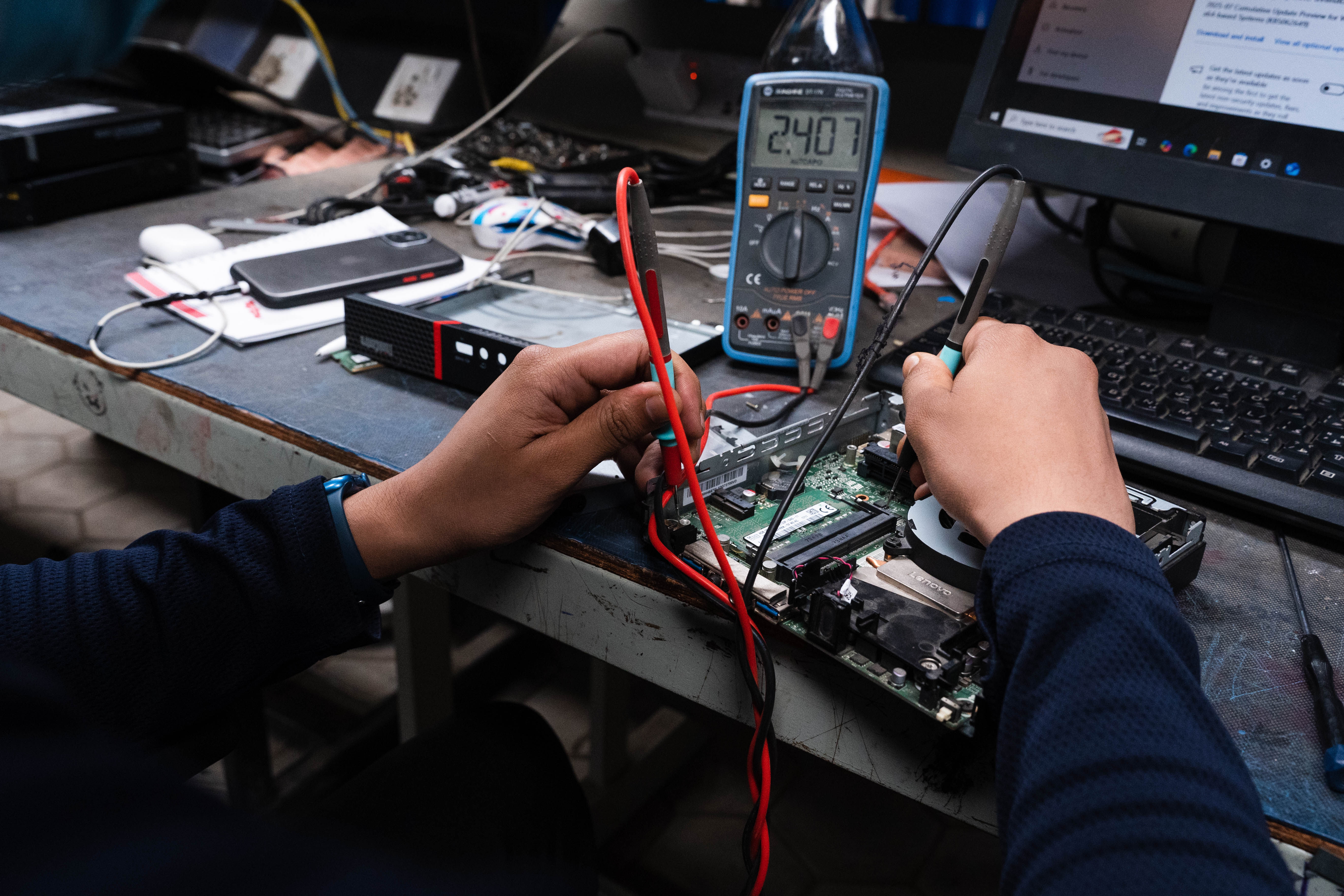

What happens to your phone when it dies

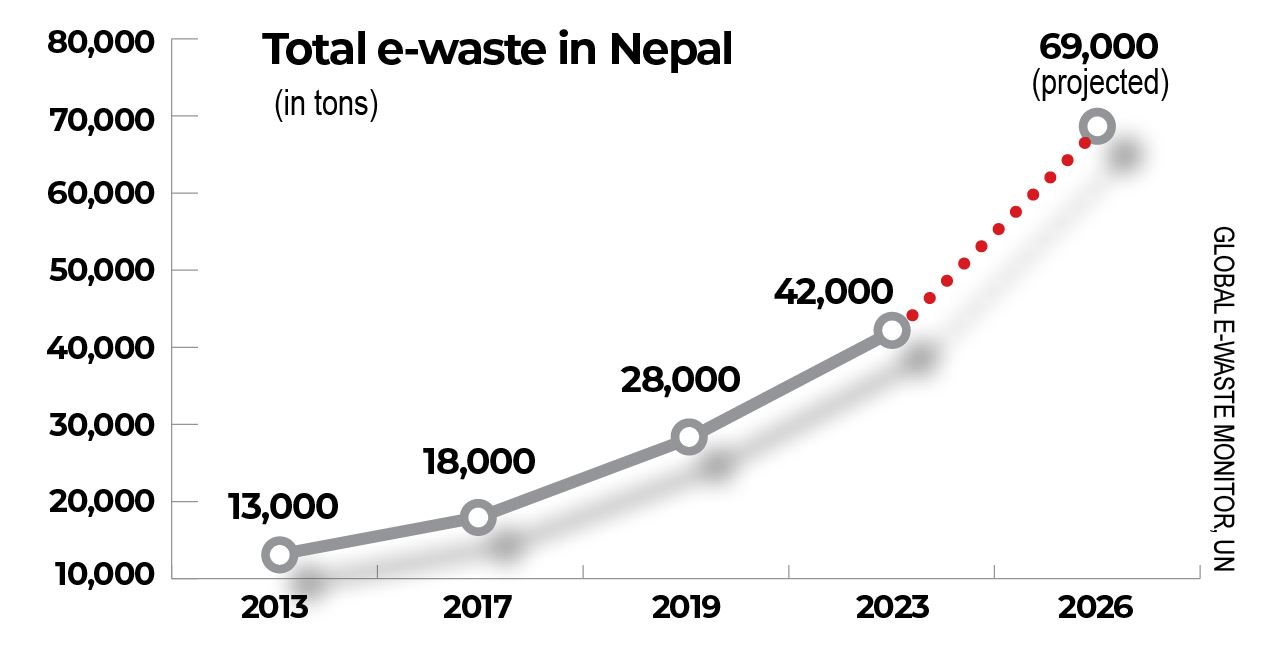

Nepal generated 42,000 tons of e-waste in 2024, up from just 13,000 ten years ago, according to a worldwide survey by Global E-waste Monitor. The figure for Nepal is projected to reach 69,000 tons in 2026.

While this is modest compared to most other countries, the growth and lack of recycling facilities are worrying.

Household appliances such as washing machines, refrigerators, cooking stoves and ovens still make up nearly half of electrical and electronic waste in Nepal, while phones, laptops, tablets, hard drives, routers and modems come next at 9%. Consumer electronics made up 17% of e-waste, followed by lighting equipment at 14%, screen and monitors at 8% and toys at 9%.

“The nature of e-waste has changed in the last decade or so, we now have less CRT monitors and CFL bulbs but more devices, solar panels, optic fibre which actually has a negative recycling value and now EV batteries,” says Pankaj Panjiyar of the Doko Recyclers.

The nature of e-waste is also guided by changing consumption patterns where people upgrade to newer gadgets every couple of years, not necessarily because they are at the end of their lives.

The average lifespan for mobile phones in Nepal is only two years, four years for laptops, eight years for televisions and computers, and ten years for refrigerators and washing machines. Just last fiscal year, Nepal imported nearly 1.9 million smartphones worth Rs24 billion.

“Businesses today, especially electronics, have exchange offers wherein customers can exchange even well-functioning goods for a newer version. By not using electronic goods to the end of their lives, we are creating a problem that wasn’t there to begin with,” says Shilshila Acharya of Avni Center for Sustainability. “Electronic use has increased dramatically, but our e-waste management capacity remains the same.”

When municipal governments have failed to even manage biodegradable waste, they have not even started thinking about e-waste. Which is why electronic and electrical waste is left to the informal sector.

There are some 1,200 scrap dealers in Kathmandu and 20% of e-waste is thought to be recycled despite the lack of proper formal channels, and most of it ends up in India.

This means limited extraction of plastic parts as well as metals such as aluminium and copper, but removal of precious and heavy elements is not yet carried out in Nepal. Liquid waste, such as acid from lead batteries, is disposed of in the dumping sites, poisoning ground water and rivers.

There is also a small but growing market to refurbish used electronic goods led by the likes of Sabko Phone which buys second-hand smartphones and reconditioning them to an almost new cheaper device.

“It was very difficult for us in the beginning to get people behind this campaign, but over the last couple of years, we have seen a change,” says Uttam Kafle of Sabko. “The fact that they are buying a refurbished phone today means they might buy a refurbished washing machine in future.”

Fourteen percent of the 1.22 billion mobile phones sold in 2023 were refurbished — that translated to 190 million fewer new phones that year. Says Kafle: “If we can associate refurbishing and upcycling with environmental gain, we will go a long way.”

Indeed, experts recommend reducing the consumption of electronic goods not required as the first step to managing waste, followed by repair, reuse, and upcycling. Recycling is often the last option, also because Nepal lacks proper infrastructure as well as a legal mechanism.

Nepal’s Solid Waste Management Act 2011 has no mention of e-waste. It has since been revised, but the document is making rounds of various ministers and is yet to be finalised. Even so, it does not have any guidelines on managing electrical and electronic waste, and has only defined the terminology.

India has an Extended Producer’s Responsibility (EPR) as well as Battery Waste Management Rules 2022 which clearly outline the responsibilities of producers, recyclers, and refurbishers.

“A national-level e-waste legislation with EPR is a must with provisions at municipalities such that there is a separate collection value chain, and such a policy should allow for recycling infrastructure,” says Panjiyar. “All of this should happen simultaneously and with public awareness about e-waste in Nepal.”

EPR will also help remove unreliable players in the market, and in turn reduce the flow of unwanted goods. This is in line with calls to curb unchecked and uncontrolled consumption of goods as well as prioritising ethical and sustainable development.

This has much relevance for the EV boom in Nepal. Of the 22,907 four-wheelers worth Rs50.88 billion that the country imported last fiscal year, 16,701 units valued at Rs41.23 billion were electric vehicles. Few of them were passenger buses, which are much more expensive than diesel ones of the same size.

Until grid-to-motor technology, such as trolley and tram, are introduced, the government must subsidise electric buses to make the best use of surplus hydroelectricity while cleaning up the air and reducing Nepal’s petroleum bill.

After all, only so many individuals can afford private EVs, and even then, they do not nearly reduce emissions as much, but add to traffic. Large electric buses also mean fewer lithium-ion batteries per person.

“Our EV adoption is both a success story and a disaster waiting to happen given all that battery waste we will be faced with soon. It is like by trying to solve one problem we have created another,” says Acharya.

Uttam Kafle at Sabko Phone says the concept of responsible use and circular economy which involves reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible, should be the way forward.

“We must make the best use of electronics for the betterment of our lives, there are still places and people without much access to these goods. But their ethical use and management, especially at the end of their life, will help save us from a lot of future problems.”

This article is brought to you by Nepali Times, in collaboration with INPS Japan and Soka Gakkai International, in consultative status with UN ECOSOC.

writer

Sonia Awale is the Editor of Nepali Times where she also serves as the health, science and environment correspondent. She has extensively covered the climate crisis, disaster preparedness, development and public health -- looking at their political and economic interlinkages. Sonia is a graduate of public health, and has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Hong Kong.