“Just walk on”

A celebration of Ani Marilyn, a photojournalist turned Buddhist nun who spent her last days spreading wisdom in NepalThe Kathmandu Valley has attracted an exceptional number of outstanding and accomplished foreigners over the decades, but few as extraordinary as Marilyn Silverstone (1929-1999).

Frances Klatzel’s book A Portrait of Ourselves, Marilyn Silverstone: From Photojournalist to Buddhist Nun, is a fitting and fascinating biographical celebration of this American woman whose life of unusual choices took her, as the title suggests, from an affluent Jewish childhood in Scarsdale, New York to becoming an acclaimed and adventurous Magnum photographer.

Roving the world, her camera captured many of the most iconic events of the 20th century, her images were published in Time, Life, Newsweek, Look, National Geographic, Paris Match, Vogue and other magazines.

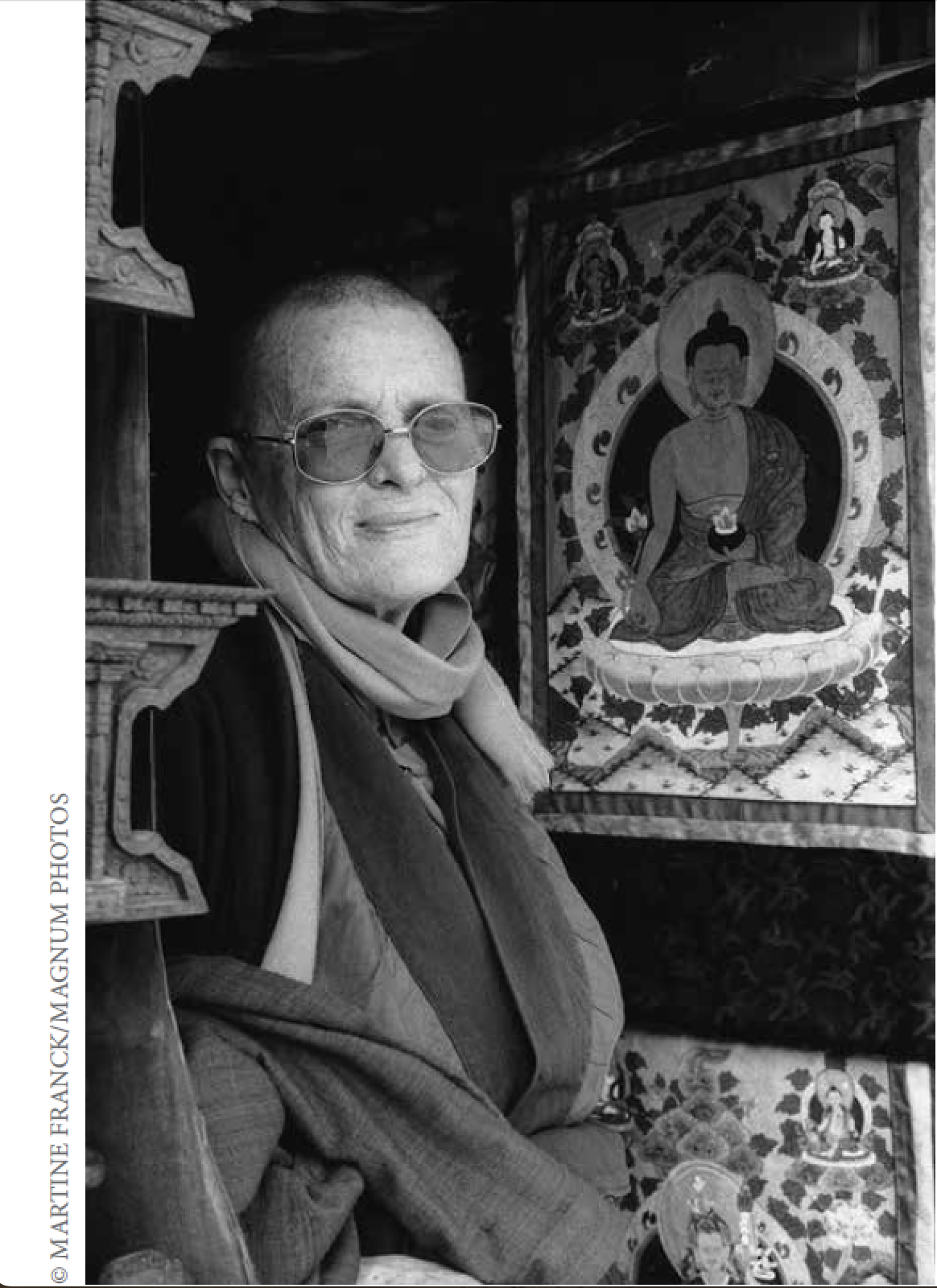

Following the teachings of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, Marilyn Silverstone devoted the last twenty years of her eventful life to living quietly and practising Buddhism in Nepal. Ordained as a Buddhist nun, she took vows in the sanctified Solukhumbu precincts of Thubten Choling with Venerable Trulshik Rinpoche in the spring of 1977.

Living in Kathmandu until her death in Shechen Monastery, which she helped create, Marilyn wrote: ‘When I look back over the years, although I did not know it at the time, ending my life as a Buddhist nun was logical and inevitable.’

Ani Marilyn was a familiar figure amid the sacred spaces of the Valley, the lanes of Boudha and even Kathmandu’s drawing rooms during my early years in Nepal, a large smiling presence draped in maroon robes, dyed sneakers, slightly whiskered, robust.

As a wedding gift she gave Tenzin and I an inscribed copy of her slim volume, Ocean of Life, aptly named for the span of her achievements and expansive embrace – editor, translator, writer, filmmaker, photographer, journalist and Buddhist nun. Marilyn’s nephew wrote: ‘Her legacy was that she was always herself no matter what chapter of her life that she was living.’

Working with a wide range of impeccable sources, Frances Klatzel has assembled first-hand the personal recollections and unsparing insights from Marilyn’s most intimate friends. One of these, Jane Abell Coon, wrote the Introduction. She was a well-known person in 1980s Kathmandu whose husband Carlton Coon served as American Ambassador to Nepal and she simultaneously as American Ambassador in Bangladesh.

The book begins with a rare message from the 14th Dalai Lama and a touching Foreword by Venerable Rabjam Rinpoche. It ends with exquisite excerpts from a Buddhist religious tract that Marilyn had translated from its traditional Tibetan text.

Marilyn’s initial trip to India was to photograph Ravi Shankar in 1955, the classical sitar maestro. Increasingly fascinated by ‘the complex and compassionate culture’ of Tibet, her Himalayan archives include images throughout India, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan.

The first internationally accredited photojournalist to base herself in India, from 1959 Marilyn lived in Bombay then Delhi, with her lifelong partner Frank Moraes, the Goan journalist, writer, commentator and first Indian editor of the Times of India after Independence.

INDIAN INFLUENCERS

I remember being taken to meet the legendary Frank Moraes in 1973, by then politically exiled in Marilyn’s elegant but chaotic London house, a magnet for South Asian intellectuals. She was not there, but Frank’s son the poet Dom Moraes was slumped desultory on a sagging sofa. My impression of Frank was well-dressed, polite and slightly distracted.

Marilyn’s talent for friendship and wide network of Indian influencers and princely connections gave her unique access to historic events, as well as recording refugees, rituals, droughts, floods, famines and funerals. In addition to maharajahs and global leaders, her images portray personal moments, ordinary people, unflinching pain and flashes of joy. She said: ‘In my job, the closer you get to people, the better off you are.’

This book is illustrated with a thrilling trove of pictures of and by Marilyn, many of which reflect the impact of Henri Cartier-Bresson who signed her up as one of the first women to join his prestigious Magnum photo cooperative.

Her assignments ranged across warzones in Vietnam, the Shah of Iran’s coronation, and Russian tanks rolling into Prague. Marilyn’s 1960s involved constant travel, her Magnum beat was the ‘Far East’, from Pakistan and Bangladesh to China, Korea, and Japan.

With a knack at being in the right place at the right time, Marilyn was the only western woman journalist to record the arrival from Lhasa into ‘safety and exile’ of the young Dalai Lama in 1959. She was at Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s funeral in Delhi, the Chogyal of Sikkim’s marriage to Hope Cooke, and with Jacqueline Kennedy on a small boat at the Lake Palace of Udaipur.

Marilyn snapped the Pope giving blessings in Bombay, Mother Teresa attending to the poor, and the Beatles on their way to meet the Maharishi. With Frank, she travelled to Africa and shot Emperor Haile Selassie in Ethiopia, Nigeria’s independence celebrations, and a very old and solar-topied Dr Albert Schweitzer in his jungle hospital in Gabon.

A Portrait of Ourselves, Marilyn Silverstone: From Photojournalist to Buddhist Nun, is a highly recommended tribute to an inspirational life, told with discerning honesty and private perceptions by those who knew her best.

Her monastic years living in Nepal continued to feature travel, hard work, undiminished curiosity, dogged fights for right, uncompromising support for others, disdain for conformity and battles with ill health, but all with her characteristic good humour.

Marilyn leaves us with some sound advice in her own words: “I can say that I did it all. The secret though is just keep walking through life without analysing it too much or clinging to it too much. Just walk on.”

writer