2002

On midnight 16 February 2002, on the sixth anniversary of the beginning of the insurgency, the Maoists launched the biggest attack till then against the state. Some 2,500 Maoist guerrillas stormed the town of Mangalsen in Achham in far west Nepal and went about strategically bombing government buildings and executing officials and security personnel.

All 57 soldiers in the Mangalsen garrison, along with 77 policemen and five civilians were killed while many government buildings and Sanfebagar airport were destroyed. Up until that point, the Mangelsen raid was the single most damaging strike by the Maoists.

Many heavy weapons were looted. Thirty-six civilian workers building an airfield were killed in Kalikot when the Army in hot pursuit mistook them for guerrillas.

The Royal Nepal Army was now in the war, and more people were killed in the next 12 months than in the previous six years of conflict.

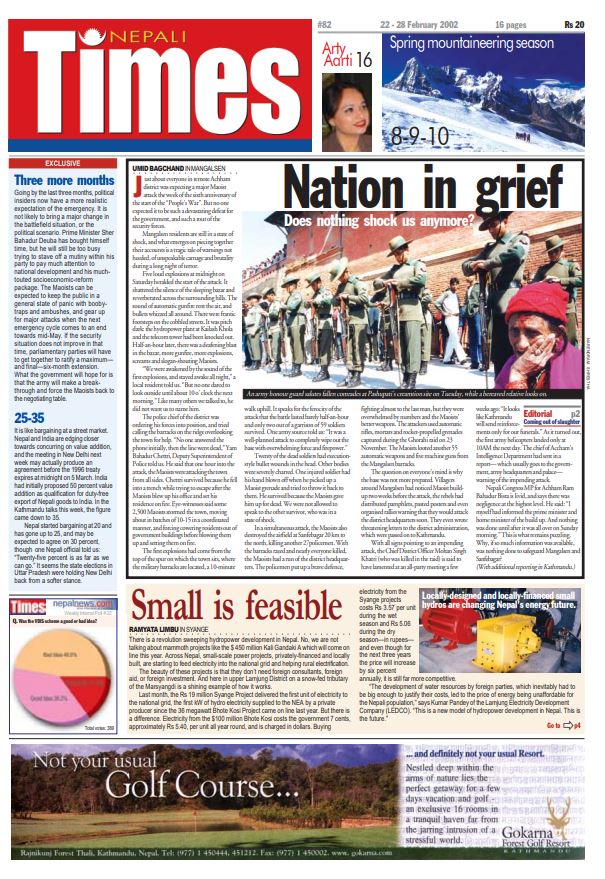

The page 1 story Nation in Grief was by Umid Bagchand. Narendra Shrestha's photograph showed an army honour guard saluting fallen comrades at Pashupati cremation site as a grandmother looked on, capturing the sombre mood of the nation in mourning.

The story read:

‘Twenty of the dead soldiers had execution-style bullet wounds in the head. Other bodies were severely charred. One injured soldier had his hand blown off when he picked up a Maoist grenade and tried to throw it back to them.

He survived because the Maoists gave him up for dead. We were not allowed to speak to the other survivor, who was in a state of shock. In a simultaneous attack, the Maoists also destroyed the airfield at Sanfebagar 20 km to the north, killing another 27 policemen.

With the barracks razed and nearly everyone killed, the Maoists had a run of the district headquarters. The policemen put up a brave defence, fighting almost to the last man, but they were overwhelmed by numbers and the Maoists’ better weapons.

The attackers used automatic rifles, mortars and rocket-propelled grenades captured during the Ghorahi raid on 23 November. The Maoists looted another 55 automatic weapons and five machine guns from the Mangalsen barracks..’

The country was shaken to its core by the devastating scale of the attack, but it was also a tragic tale of warnings not heeded.

As Bagchand reported for Nepali Times the week following the attack, the Maoists had distributed pamphlets, pasted posters, organised rallies warning of an impending attack on the district headquarters, and sent threatening letters to the district administration which was passed on to Kathmandu.

The Chief District Officer Mohan Singh Khatri, who was killed in the attack, had said at an all-party meeting a few weeks prior that Kathmandu would likely send reinforcements only for their funerals, and as it turned out, the first army helicopters from the capital landed at 10AM on 12 February, just to pick up the corpses.

In an editorial that week titled Coming out of Slaughter, we said that this cannot continue any longer and a real solution was in non-violent struggle, democracy, and social progress.

‘We have a situation here: democracy is threatened by an ultra-violent group that does not believe in it. Their reach has widened dramatically in the past six years, and they have used brutal violence to cleverly fill the vacuum left by the state.

And as the threat to our democracy and freedoms get more and more serious, our parliamentary parties and factions within them continue to use that threat to bring each other down.

Successive rulers since 1996 have squandered the political option: the civil police couldn’t fight the war so an armed police force was set up, the laws of the land were not enough and the anti-terrorism act was needed, constitutional provisions did not suffice and so an emergency was declared and the army unleashed. And the problem is still there. If anything, it is getting bigger.’

And bigger it did get. The Maoist war had already cost 3,200 lives until then, but would go on to claim more than five times that number by the time the peace accord was signed in 2006, and the former rebels were brought to mainstream politics.

But the absence of war didn’t mean peace, as we found out in the years since.