Nepal’s incomplete revolutions

Political and democratic movements of the past decades have all fallen short of citizen’s expectationsFor daring to demand democracy, the Rana regime hanged activist Shukra Raj Shastri at midnight on 24 January 1941 by the side of the road at Teku. Across town in Siphal, Dharma Bhakta Mathema was also hanged. Four days later, Dasrath Chand and Gangalal Shrestha were executed by firing squad.

These four young revolutionaries were members of the underground Nepal Praja Parishad that led the anti-Rana revolution with plans to assassinate key figures of the dynasty.

The four martyrs sacrificed their lives for an unfulfilled cause. Monuments were put up in their honour (Shahid Gate) and their names glorified by the Shah monarchy that itself went on to ban political parties and persecute democracy activists.

In 1950, the newly-formed Nepal National Congress launched an armed uprising against Rana rule after King Tribhuvan sought refuge at the Indian embassy to flee from the Rana regime. In 1951, the Ranas, Nepali Congress and King Tribhuvan signed a tripartite agreement that brought an end to 104 years of Rana rule.

Thus began contemporary Nepal’s cycles of unfinished revolutions.

Some 75 years later, on a sunny September morning, Nepal’s young and hopeful took to the streets demanding an end to the nation’s corrupt polity, envisioning a better democracy. They organised through digital platforms, played songs, danced, and chanted slogans.

A few hours later, commandos fired on the protesters, massacring dozens. Over 8 and 9 September 2025, the government was overthrown, constitutional bodies were literally reduced to ashes, and 74 Nepalis were martyred.

Nepal’s periodic revolutions have been ignited by anger against rulers, they have begun with great promise, spread with enthusiastic popular support despite rulers trying to crush them — but ultimately they have always fallen short of the expectations of citizens demanding reform.

Through decades of dissent, Nepal’s periodic revolutions have remained incomplete, with the nation caught up in a cyclical search for stability.

In 1960, king Mahendra staged a coup and overthrew an elected government led by prime minister B P Koirala -- a royal revolution against democracy. Mahendra is reported to have famously said to Koirala: “Nepal is not big enough for the two of us.”

For the next 30 years Nepal resembled a one-party state under the absolute monarchy of the Panchayat. Elected leaders languished in jail or exile, political parties were banned, and the press controlled. This was the most frigid period of the Cold War, with Nepal’s neighbours India and China at war. Geopolitics was bound to have an impact.

“After the 1816 Sugauli Treaty with British India, external forces magnified internal power struggles as outsiders played divide and rule,” explains editor and political analyst Rajendra Dahal. “Movements did not reach a logical conclusion because domestic politicians were forced to compromise.”

Indeed, the departure of the British from India in 1947 meant that the days of the Anglophile Rana regime were numbered. Successive prime ministers sought patronage in Delhi, and the monarchy tried to counterbalance it with a policy of equidistance with China. The neighbours showed a keen strategic interest in Nepal’s domestic politics.

“The Panchayat system did not deliver what it promised,” says Santosh Sharma Poudel of Nepal Institute of Policy and Research. “Nepalis suffered administrative and governance failure, politics was centralised in Kathmandu, leaving out the rest of Nepal.”

With mainstream political parties and leaders were underground between 1961 till 1990, student activists became proxies for political parties. As pressure for change grew, a student-led pro-democracy movement spread across Nepal in 1979. In response, King Birendra announced a referendum to allow Nepalis to choose between the status quo and a ‘reformed’ Panchayat system.

The Panchayat won by a slim margin with questions about the legitimacy of the plebiscite. The reforms never materialised and it would be another decade before street anger boiled over again. As the People’s Movement for democracy spread, king Birendra again relented, unbanning political parties and Nepal became a constitutional monarchy.

Inspired by Mao Zedong, a faction of Nepal’s Communists felt that western-style parliamentary democracy was too slow to end a feudalist monarchy. They launched an armed struggle in 1996, and the war lasted ten years (editorial, page 2).

“If the democratic government post-1990 had performed better, and brought real reform, the Maoists would not have a reason to launch a revolution,” says Poudel.

After nearly a decade of bloodshed that left 17,000 dead and thousands still missing, the Maoists joined forces with the democratic parties that they had been fighting, to pressure king Gyanendra through street protests in 2006 to restore democracy.

In 2008, an elected Constituent Assembly abolished the monarchy. Recalls Rajendra Dahal: “The second people’s movement did not aim to abolish the monarchy. In fact, the reinstated parliament even granted equal rights for royal daughters to be crowned queen. But eventually, the monarchy no longer fit the political framework that the parties envisioned.”

It took two elections over the next eight years to draft a new Constitution that reflected Nepal’s socio-cultural and geographic diversity and met the demands of the Maoists. The new federal Constitution was finally promulgated in 2015, but failed to satisfy India and the aspirations of the Madhes communities for autonomy. The state’s effort to crush the Madhes movement cost 45 lives.

The promise of the new Constitution was squandered over the next decade with rotating leadership of the NC, UML and the Maoists — all of whom had forgotten the sacrifices made in the name of revolution. Cronyism and corruption was the order of the day. And it was this never-ending cycle of political opportunism and malgovernance that brought Nepal’s youth to the streets on 8 September.

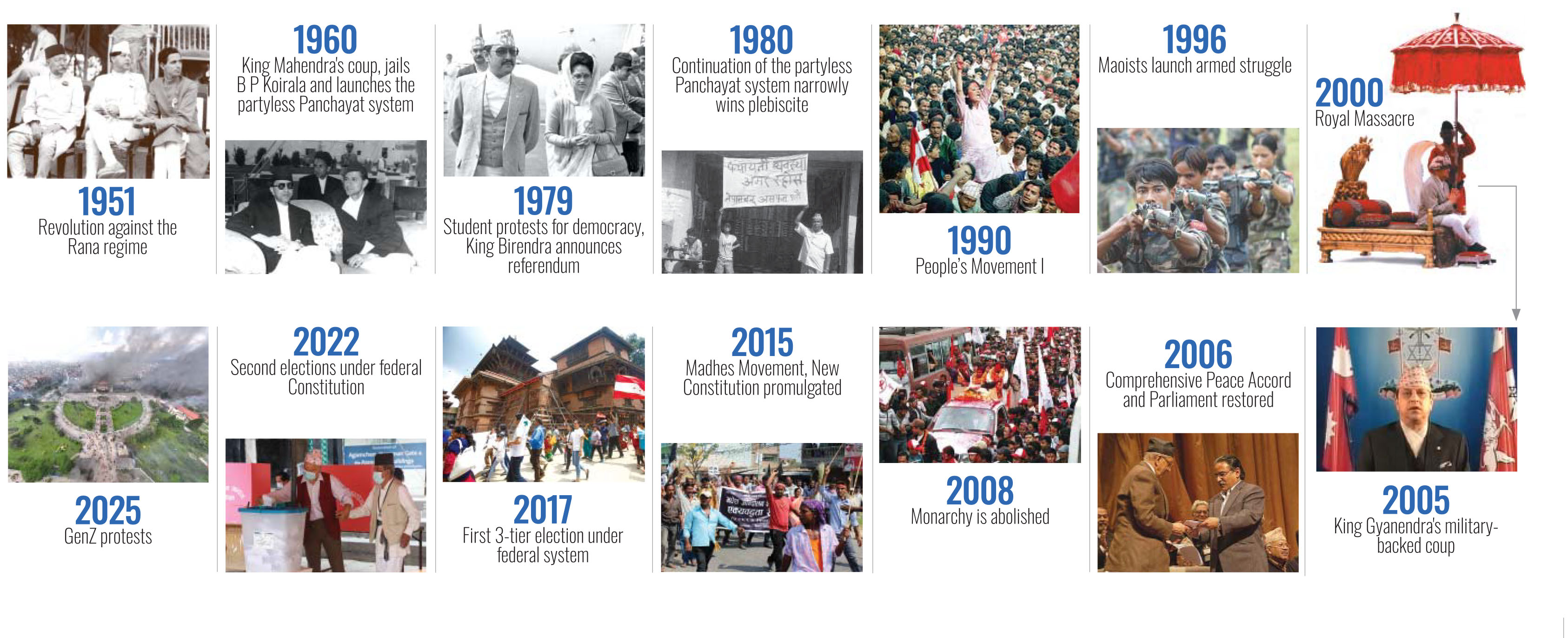

1951 Revolution against the Rana regime

1960 King Mahendra's coup, jails B P Koirala and launches the partyless Panchayat system

1979 Student protests for democracy, King Birendra announces referendum

1980 Continuation of the partyless Panchayat system narrowly wins plebiscite

1990 People’s Movement I

1996 Maoists launch armed struggle

2000 Royal Massacre

2005 King Gyanendra's military-backed coup

2006 Comprehensive Peace Accord and Parliament restored

2008 Monarchy is abolished

2015 Madhes Movement, New Constitution promulgated

2017 First 3-tier election under federal system

2022 Second elections under federal Constitution

2025 GenZ protests

BRK ALLIANCE

“The socio-political change sought in all these movements never matched the people’s expectations, because the central issue of clean and efficient government never materialised,” says Poudel.

The post-September political landscape has injected new personalities and alliances still relatively new to politics, as evidenced by the new electoral partnership of the BRK — Balen Shah, Rabi Lamichhane, and Kulman Ghising (page 1).

These leaders are not without flaws, but they have become the effective flag-bearers of the GenZ movement, hoping to represent Nepalis disillusioned by decades of democratic decay. The March election will pit them against the legacy parties.

There is already criticism that BRK is behaving just like male-dominated opportunists of old parties. The troika is resembling the triumvirate of Oli, Deuba and Dahal and its culture of patronage and quid-pro-quo power-sharing between alpha males.

Will this also be another unfinished revolution? Says political scientist Sucheta Pyakuryal: “The kind of destruction that happened after the revolution should have been followed by a ground-breaking shift in Nepal’s political ecosystem, but that did not happen. Today the situation is a lot grimmer because we have players who have learned how to use the democratic facade to sound ‘equitable’ and ‘accountable’. But look closely and you see how the same political chauvinism, cronyism and nepotism still continue.”