Two schools of thought

After nearly two years of disruptions, Nepalis are itching to get back to normal lives. But there are signs society is returning to an old normal.

As soon as the daily caseload and infection rate started falling, the lockdown was lifted even while more than 10% of those tested are still Covid-positive, there are still nearly 500 people in ICU and ventilators in hospitals, and the Delta variant is infecting even those vaccinated.

And now schools are set to open next week. While we understand that there has been a tremendous social cost to students not attending in-person schools for nearly two years, why was there a need to reopen just for a few weeks before the holidays?

Some teachers, not all, have only just got their first vaccine doses, and unvaccinated children will now be in crowded classrooms, and then going home for family and festival gatherings for Dasain-Tihar-Chhat.

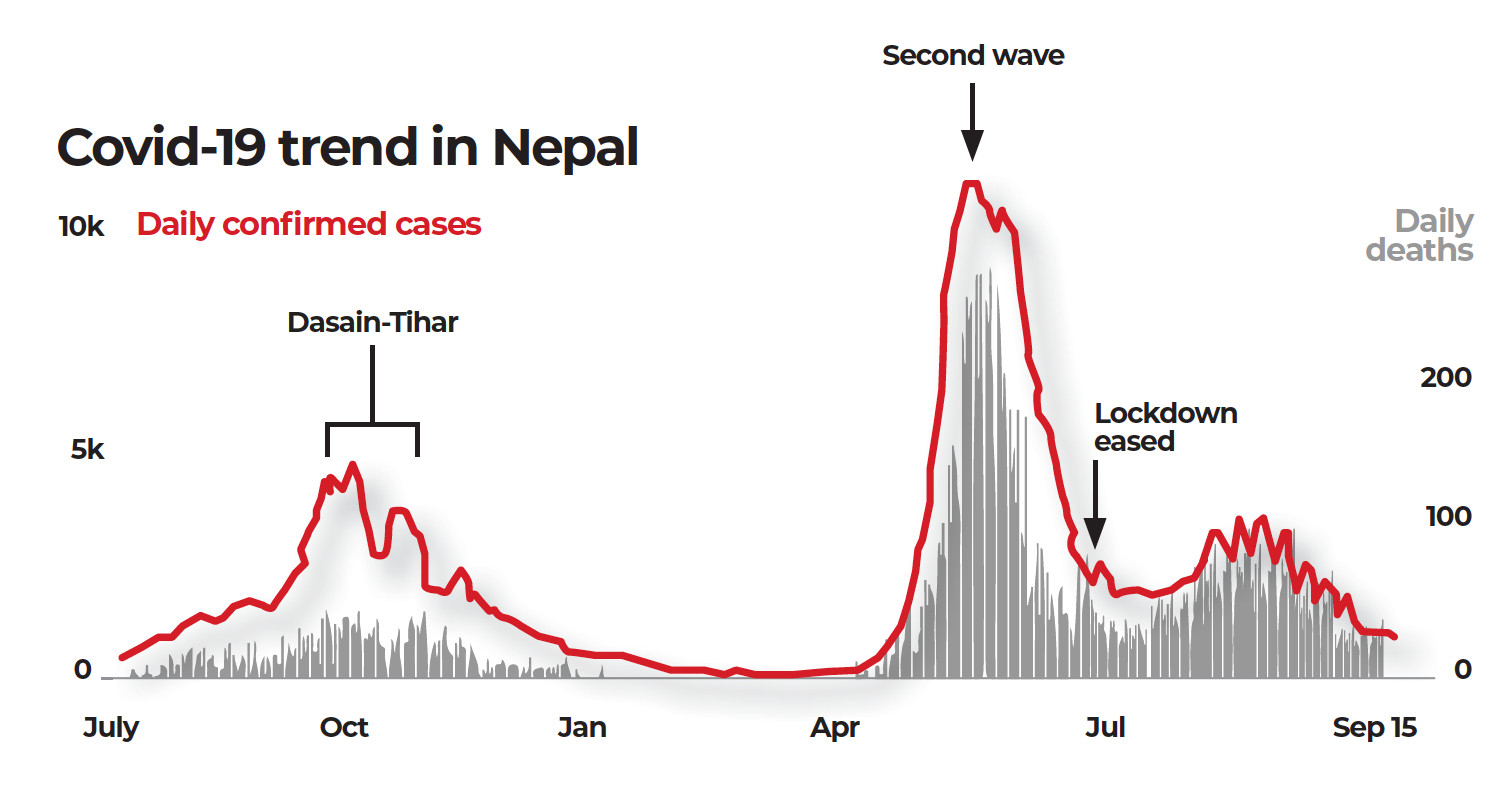

As our report this week warns, we have been at this point before. Last year this time, the government relaxed the lockdown and millions travelled to their hometowns. Cases soared as the first wave peaked during the holidays (see graph).

Experts have told us that a third wave is not likely, given that 20% of the population are now vaccinated (probably rising to 30% by Dasain), as well as the presence of natural antibodies detected in nearly 70% of the population in a recent sample sero-prevalence survey.

However, we cannot let our guard down. Delta is a sly virus, just waiting for an opportunity to pounce, and exploiting every weakness in human behaviour.

Experience from Nepal and other countries have shown that fully vaccinated people can be infected, and spread the virus to others, including elderly and unvaccinated children at home. Because of Delta’s high transmissibility, experts warn that labels like ‘herd immunity’ and ‘breakthrough cases’ do not make sense anymore.

By the time Nepal reaches 40% vaccinated population by December, it will also be time for the third booster shots. We also do not know how long the natural immunity will last in the 70% of the population with antibodies.

Studies in India and elsewhere have shown that lockdowns and a high seropositivity rate did not protect children from being infected with Covid-19 if family members were not careful about mingling and mask-wearing.

Research also shows that the risk of infection in the classroom is low if students wear masks properly at all times, and are physically separated in well-ventilated classrooms.

Experts predict that there will be a slight increase in Covid-19 cases among students, teachers and family members at home when schools resume in-person classes. But as vaccination rates rise, and in areas with high sero-prevalence, it may not lead to another spike, or even a third wave.

What no one can tell us is how ‘slight’ this ‘increase’ in Covid-19 cases will be in Nepal – especially since the vaccination rate is still low and most classrooms, school buses, playgrounds are crowded, and children will be excited to see each other after so many months away from friends.

So, while the benefits of resuming physical classes may outweigh the risks, the government has been ill-advised to restart in person lessons just a few weeks before schools close again for the holidays.

Instead, it should have used the coming weeks to launch a saturation awareness campaign with strict criteria for school opening, citing mask-wearing at all times, spacing and limited mingling. Parents, teachers and students must be convinced that the risk has been minimised, and the cost of denying children education now exceeds the risks to them from Covid.

Across South Asia, school closures and limited digital learning have deprived children for a prolonged period from education, widening socio-economic inequalities. In Nepal, the digital divide has created an education divide with most of the 80% of students who attend government schools deprived of learning since March 2020.

Most students have missed at least 70 weeks of school since the pandemic. Of the 29% of children in a recent survey who said they had access to distance learning via radio, television or online, only half were actually using it – mostly in cities and private schools. The pandemic has wrecked Nepal’s gains in school enrolment, especially among girl children.

While keeping schools closed does not prevent the Delta variant from spreading, they should not reopen without precautions in place – and only after the festivities. Public awareness campaigns are needed before in-person classes resume, and compliance must be monitored. Last but not least, expedite full vaccination of teachers and school staff nationwide.