Pancha Kumari Pariyar: Still She Rises

“When the stalks of rice grow taller, you must come back here again,” she says. “They move in the wind like waves in the ocean.”

Standing on the balcony of her home in Sano Gaun of Lalitpur, where poet Pancha Kumari Pariyar lives with her husband and their 8-month-old son, I am struck by the sight of green –– that there is any left, and what respite even a small patch brings.

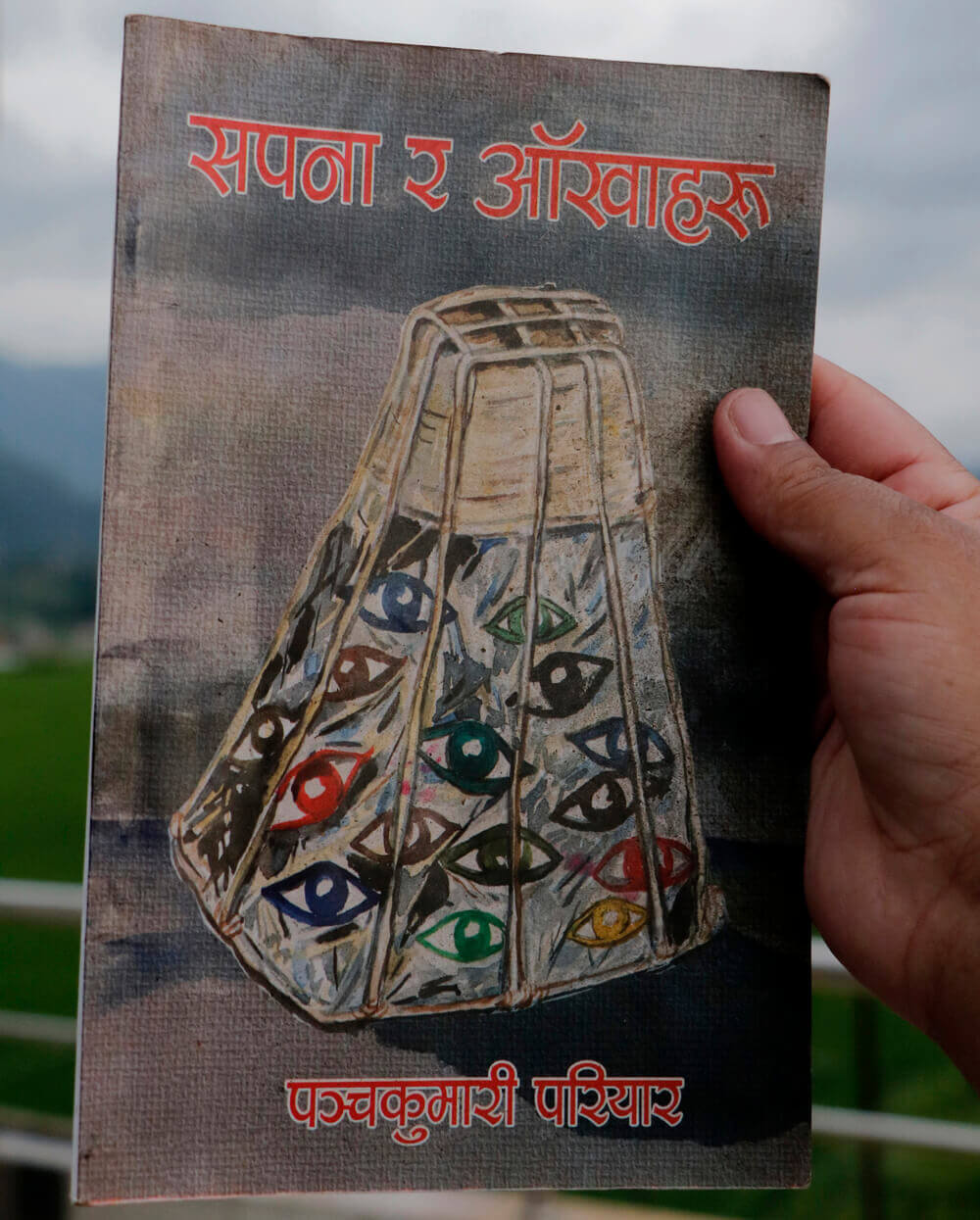

Pancha Kumari’s poetry is much like that patch of green, a long deep breath in a literary scene dominated by non-Dalit voices. Born in 1979, in Buipa of Khotang, Pancha Kumari has published two books of poetry. Her first collection, Sapana Ra Ankhaharu (Dreams and Eyes, 2005) includes poems written from 1998-2004 between Dharan and Kathmandu.

When her second book, Juthi (Juthi, 2013) was brought out by Sajha Prakashan, Pancha Kumari became the first Dalit woman to be published by Nepal’s oldest and most reputable publication house. The titular poem, Juthi, is currently taught at Purbanchal University. When asked if the name Juthi means anything, Pancha Kumari tells me it is the name of a low-caste Dalit woman. It was her friend, Raju Syangtan’s idea. “Raju bhai reminded me of the struggles I had to go through as a Dalit woman to arrive here. He said I should honour my journey by naming my collection after an ordinary Dalit woman, because I, too, am Juthi. Let ordinary Dalit women also be protagonists in Nepali literature, why not?”

Read also: Shanti Chaudhary: Poet-at-large, Muna Gurung

Besides writing, Pancha Kumari has worked as a social mobiliser on projects under the Rural Development Fund, the Dalit Welfare Organisation and the National Planning Commission. She also ran a literary radio program on Mero FM, where she invited Nepali writers for interviews and readings. Pancha Kumari was the editor of Dalit Darpan, a leftist publication of Dalit writings. She is a member of the Maoist party, and says she was drawn to the party’s ideals because she wanted equality for Dalits, Muslims and women. “I cannot say that the war benefitted individual lives and families, but on a larger political level the Maoists uplifted the Dalit community and made us more visible.”

In this month’s Lightroom Conversation, Pancha Kumari and I talk about writing through injustices and rising, winning in all sorts of life’s competitions, the importance of girlfriendhood, and the need to build healthy writing communities for women.

Pancha Kumari Pariyar: All I wanted to do was win.

Muna Gurung: What was the prize?

P: Thin notebooks, small diaries, pencils, ballpoint pens –– there would be so many, I could barely carry them in my arms. I started writing in 4th grade and I would come first in class or in competitions within the school. But by 5th grade, I was competing at local and district levels. I wrote about the hurt I carried in my younger years, but more than the poems, my focus was always about being 1st, 2nd or 3rd. I didn’t want to be any less. (Laughs)

M: I relate; I do anything for free pens. But, can you tell me a little bit about the hurt?

P: In Buipa, we were bound to the baalighare system. I grew up seeing my parents and my brothers work for other people –– tilling their land, harvesting their crops, doing all the field work. As Pariyars, we are musicians by caste, but we also made clothes. So, for a year’s worth of working on other peoples’ lands and making their clothes, they would compensate us with a few baskets of millet or corn, but never rice. And money? We never saw the face of it. I began working in the fields with my family when I was 7 or 8 years old. But my parents sent me to school. There, I was the only Dalit girl. Up until 4th grade, I was not allowed to sit on the benches with my peers. I would have to stand throughout the day. Some teachers who felt sorry for me would allow me to sit on the floor, but otherwise I stood through all the subjects. How did I do it? Nowadays, I can barely stand for half an hour.

Read also:

Bina Theeng Tamang: More than a maichyang, Muna Gurung

Anita Tuladhar: The Gardener of Small Stories, Muna Gurung

M: Did your friends fight for you?

P: I walked to school with my friends. But as soon as we entered the classroom, they would not let me sit on the benches with them. In those days, my mind was sharp, and I even helped them with homework. But afterwards, over something small like touching their glass of water, they would hit me, spit on me. This was normal, everyday behaviour. I don’t blame them, though. They were part of a larger system, and so they enacted the roles they were taught by the same society that allowed me to be treated less than human.

M: Did something shift in 5th grade?

P: I started sitting on the benches. You see, by the end of 4th grade I was already writing and being recognised as a smart student. There was something in me that said, whether I write about my pain or not, whether I sit on the benches or not, they will still scold me, call me names, hit me, tear my school notebooks, steal my pens. So, I made up my mind to always write about my pain and speak my mind.

M: This reminds me of what poet Audre Lorde said about putting silence into action and language because death will be the ultimate silence, whether we choose to speak or not, we will all die. Were you scared that they might hurt you more if you wrote?

P: Never. What more could they do? Maybe kill me. But I was already living a life that was lower than that of an animal. And slowly, as I won more prizes in competitions judged by non-Dalits and Bahuns, it gave me the confidence to sit down with them.

M: It validated your existence.

P: Exactly. Yet, I have always felt that if I had not endured the struggles of being Dalit and therefore considered sub-human in this society, perhaps I would not have become a writer today. I would not have understood the importance of politics, either.

Read also:

Toya Gurung: Nepali Literature's Thulnani, Muna Gurung

Maya Thakuri: Writing between the lines, Muna Gurung

M: But surely, we hope that other Dalit women will not have to go through the same struggles and pains just to become writers. Was there anything you read by Dalit writers or any writer that moved you to become one?

P: When I read Parijat’s Naikape Sarkini, I suddenly realised that not only was I Dalit and therefore one of the lowest people in society, but I was also a Dalit woman, which made me different from a Dalit man. Parijat’s story is about a Dalit woman who works as a day labourer hauling sand from the river, and because she does not have enough clothes for the winter, her body is so cold that even the sun cannot touch her. Later, we see her go home and take care of her disabled husband, who berates and mistreats her. I understood that the Sarkini was less powerful than a disabled Dalit man. Before reading the story, I had not thought about the difference in gender within our community, I just saw us as a united group who suffered together. But I was wrong. There is a hierarchy, and it became clear to me that it wasn’t enough for me to just write for my people, I had to write for Dalit women.

M: Do you find that you have reached Dalit women?

P: I don’t know, but when I published Juthi in 2013, I invited all my friends and acquaintances from the Dalit community to the launch. It was a historic moment because in 100 years of Sajha Prakashan’s existence, my book was the first they had published that was written by a Dalit woman.

M: It took them 100 years?

P: Yes. There are not many Dalit writers in Nepali literature and within that, the number of women writing is dismal. There is Dhan Kumari Sunar who writes, but she doesn’t have a book out. Sobha Dulal is another writer… there are other essayists, but see, I shouldn’t have such a hard time coming up with names, but that’s the reality.

M: How do we change that?

P: Honestly, I feel like I haven’t done enough to ensure that more Dalit women are writing. I should start researching deeper and find ways to create space and opportunities for us to write. I also believe that supporting women who are already writing is crucial. For instance, the launch of Juthi was a historic moment but I couldn’t celebrate with my Dalit community because they didn’t show up. It was a bittersweet moment for me. A few years later, the National Dalit Commission honoured me at a program, and that brought a sense of relief. It’s different when your own people honour you.

M: What’s the difference?

P: It is this feeling … that my words have finally reached the people I am writing for, and that they are listening.

Read also: Factory of questions: Sarita Tiwari, Muna Gurung

M: What does your family say about your writing?

P: Buwa passed away when I was 10, so he didn’t get to read my work, and when I was pursuing my IA degree in Dharan, Ama passed away. She and I had been living with my brother then: he had a tailoring shop and I used to work for him. I call Dharan my literary home. It is where the writer in me took off. There were many readings, events and gatherings of writers that happened in those days. I wanted to attend all of them, but my brother would scold me: Why are you wasting your time on this nonsense? Focus on your course book, not novels! Like many others, my brother thought that writers were mentally ill; they were people who had too many feelings and who blindly trusted their hearts over their minds. Since he wouldn’t let me go to anything literary in Dharan, I had to constantly lie at home about going to a friend’s place to study, but really I was attending a reading, or taking part in a competition.

M: So clearly your brother did not read your work.

P: No. But in Dharan, once a month, the local newspaper, Dharan Today, would give out a box of Mayos instant noodles to the best piece of writing. That month, one of the poems I had submitted had won. So, I brought home a box of instant noodles. It was the first time that my brother didn’t scold me for writing. Maybe he thought, Oh, you can get to eat if you write. (Laughs) After that, if my brother scolded me, I would turn it into a poem. If my sister-in-law screamed at me, I would make a poem out of her anger. Slowly, they realised they couldn’t stop me and so eventually, they let me be.

M: Was it hard to become a writer in Dharan?

P: Dharan had a bubbling and lively literary community but it was made up of all non-Dalit writers. I had to prove myself, especially to the male Bahun writers who judged most of the work. At the beginning, I didn’t know much about imagery, metaphor or any other techniques in writing. I just wrote what I felt, what I saw. So, I would share my poems and they wouldn’t pay attention to them. I was just learning then, and I could have given up, but I was not used to that. Remember, I was the girl who would rather stand through all her classes than quit. So I kept reading the same group of writers. I kept writing, over and over again. I always showed up to everything until the same people who rejected me began to recognise me and my work. I also think that it is easy to establish oneself in a small place, if I had been in Kathmandu in those early days, I might have disappeared in the crowd.

M: Do you have a first reader that you share all your work with?

P: I had the best reader – my pen pal, Shanta Rai. While I was still in 7th grade in Khotang, I used to write to her. There was a radio program that connected people who were interested in writing. I do not remember what we wrote to each other, but she always said she loved reading my letters. She was from a village in Morang, and when I moved to Dharan we became even closer. After ama passed away, my brother tried to marry me off. I protested, left his home and rented a flat with Shanta. It was the best year of my life. She loved me so much. She would cook, do the dishes, clean the floors and all I had to do in return was read my poems to her. After I read to her, she would tell me which ones I should send to which magazines and competitions. And the ones she picked always got some recognition!

M: I’ve always believed in the importance of girlfriendhood. It is the strongest and sturdiest kind of love a woman can get. I hope you write about Shanta ji.

P: I want to because I miss her. We had created our own little world that year. Shanta would bring rice and dal from her home. I was a tailor at my brother’s tailoring shop, which made me some money to pay for rent.

M: And you could sew all sorts of fashionable clothing items for women. You two were set!

P: (Laughs). I had another close friend, Srijana Rai. But you know, I haven’t been in touch with either of them for years now. In 2001, I came to Kathmandu to pursue a diploma for social work. I lost my phone and with it, I lost both Shanta and Srijana’s numbers. I’ve looked for them on Facebook, but I can’t find them. I wish I could go back to my Dharan days.

M: After Shanta and Shrijana ji, did you have any other trusted reader? How necessary is it for writers to share their work for feedback?

P: Writers need feedback, yes. But we should also be careful about who is giving us the feedback and how that lands on us. When I was completing my Master degree at Ratna Rajya Laxmi Campus (RR), I frequented a bookstore outside RR. One day, the bookseller and I got to talking and he asked if I wrote. I showed him some of my poems. He read them and said, How is this considered poetry? This is not how you write imagery. This is not good. I was completely crushed but I thanked him and walked away.

M: We have to learn who to entrust with our work and when. We are lucky that you were already pretty established as a poet, then. If it had been someone who was just starting out, to be shut down like that would have been dangerous.

P: Exactly. Also, people can only give you the kind of feedback that they are capable of defined by time, space, their histories, knowledge –– it does not mean what they are saying is what you need or should want to hear. But I have also had some really great experiences with sharing work, too. A few years back, I used to be a part of a circle of friends who met regularly. We were all women and we all wrote. In the group, there were five of us: Nibha Shah, Gauri Dahal, Sobha Dulal, Chandra Thane and me. We met in one person’s house, shared our work and received feedback. Then we would go to another person’s house the next time.

M: I love that the five of your carved out this space for yourselves, and what a healthy way to write in this crazy city.

P: But we stopped! I do not even remember how or why ... we met 3-4 times, and then I guess life happened. We have husbands, families, and children. I mean look at me now. I used to write 3-4 poems a day, but now I have let 3-4 years to pass by without having written a single new poem.

I have suffered some terrible physical ailments, and just life after marriage has become uneasy. My husband is Bahun, you see, and I am not really accepted in the family. And on top of that, now that I have an 8-month-old child, I don’t have any time. I wake up with him, and spend my entire day caring for him, then I fall asleep next to him. My life reminds me of that poem that Sulochana Manandhar didi wrote… what was it –– something about naniko thangna…

M: Yes, I love that poem, it’s called Grihiniko Kabita (Housewife’s Poem) and goes, ghaintokopanima / nanikothangna ma pani / kabitaharu jhuljhulgari janminchan… About how poems are born in kitchen corners, in water containers, in baby’s rags...

P: Yes, that one. I feel like that poem was written for me. I fully live in that poem these days. The hours I would have otherwise given to poetry, I spend on my child and family now. But I try to stay positive. I tell myself that if I used to be the mother of my poems, I am now a mother of an actual human I created. (Laughs)

M: That is such a beautiful thought. And also to remember that you come from a long line of artists and creators.

P: Yes, I have always believed that Dalits are one of the most artistic groups of people. We are divided into sub-groups with specifically artistic jobs assigned to us at birth: we are singers, musicians, tailors, cobblers… We have always been creators and engineers, and we have always created in the name of serving others. (Pauses). Maybe it is time to serve ourselves.

Cloud, daughter, and me

Translated by Muna Gurung

On a moonlit night

in a corner of the sky, I saw

a cluster of white clouds

like cotton, a cluster of warm clouds–

many blankets were made

some mattresses

and a few pillows.

Suddenly,

a voice pierced my quiet,

my daughter woke up crying:

“Ama, I’m cold–”

I cannot cover my daughter with those blankets of clouds

and my arms alone cannot keep her warm

the moon is dimming

the cluster of warm clouds is disappearing–

I’m growing cold

and she is like ice, snow.

The warmth of just a few moments ago

– of blankets, mattresses and pillows –

have grown cold with the night

now, one by one, they slowly freeze,

and die.

7 June, 2000

Lightroom Conversation is a monthly page in Nepali Times on interesting figures in Nepal’s literary scene. Muna Gurung is a writer, educator and translator based in Kathmandu. munagurung.com

writer