पुतली बाजे and the metaphor of metamorphosis

Admiring his Uncle Bob’s butterfly collection as a young boy in England in 1950, Colin Smith had no idea that the fluttering insects would eventually become his life. Not in the UK, but in faraway Nepal.

As a Boy Scout, Smith’s fascination for butterflies grew as his uncle taught him about the metamorphosis in the life cycle of these fascinating insects.

Before long, Smith was collecting butterflies himself, while also preparing to enroll at the Imperial College in South Kensington. In 1964, Smith came to Nepal as a teacher for United Mission Nepal (UMN).

“I was told that alongside teaching, I needed to have a hobby, too. I told them that I collected butterflies,” he says. He was asked to make a collection from Nepal to bring back home.

It is a sunny January morning and Smith, now 85, sits in a thin half-sleeved shirt in his garden in Pokhara. He has lived in Nepal for 55 years now, the last 25 of them with Min Bahadur Pariyar’s family in Lamagaun near Pokhara.

Smith taught Math and English around schools in Pokhara and Kathmandu, which is when he met Dorothy Merow, who taught at Pokhara’s Prithivi Narayan Campus and had started a small natural history museum there. She persuaded him to collect butterflies for the museum.

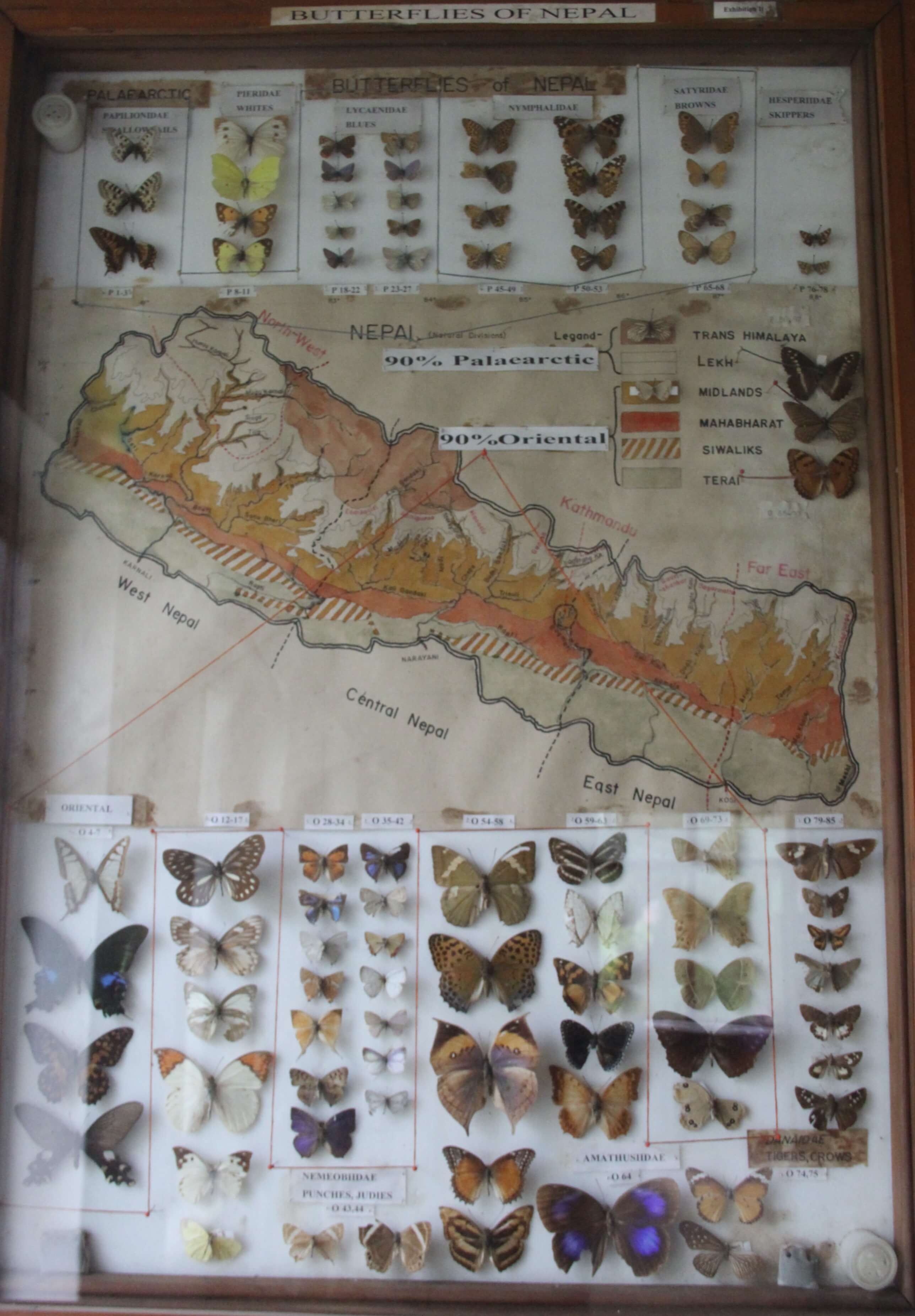

He also started collecting and photographing rare butterflies from all over Nepal for Tribhuvan University and the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP). Most of his butterfly collections are exhibited at the ACAP-managed Annapurna Natural History museum inside Prithivi Narayan Campus.

But then a new reality set in. “It was one thing to collect butterflies as a hobby, but it was another thing entirely to do it every day," says Smith, who was travelling all the time from Dharan and Ilam in the east, to Gorkha and Sukhlaphanta in the west.

“No one knows why, but Godavari is the best place to find butterflies in Nepal, and why more than half the species in Nepal are found here,” says Smith, recalling his days with friend and fellow butterfly expert Mahendra Limbu exploring the biodiversity-rich mountain south of Kathmandu.

Nepal is one of the best places in the world for butterfly watchers. Of the 17,500 or so species of butterflies in the world, 660 are found in Nepal, and 20 of them are on the endangered list. There is great potential if Nepal marketed expeditions in the peak butterfly watching seasons in March–June and August–October. Smith believes it is important not just to show visitors Nepal’s fabulous diversity of butterflies, but also detailed information about each species.

During this time, Smith began writing articles on butterflies for academic journals, which led to his first attempt at making a comprehensive checklist of butterflies in Nepal. He would go on to write four more books about butterflies and moths which are now used as school textbooks.

In the early 2000s, Smith began working mostly on moths, collecting for Kathmandu University. “I used to travel around with a fluorescent bulb in a white sheet to collect dead specimens in the evenings,” says Smith, who has come to be known as पुतली बाजे, as he ages into his hobby. “Butterfly Grandad” is also what Uncle Bob’s own grandchildren call him back in England, so it was a fitting Nepali nickname for Colin.

Min Bahadur and his friend Surendra Pariyar met Smith as young boys during a camping trip to Rupa Lake. They showed an interest in collecting butterflies and in the process, formed a deep bond.

“He taught me everything there is to know about butterflies,” Surendra says. He and Min Bahadur sit beside Smith as the sun illuminates the south face of Machapuchre. The butterfly collection is now at the International Mountain Museum, and Smith’s photographs are postcards.

The printed postcards do not sell anymore because of the collapse of tourism and the demise of the postal service, so Smith hands them out to children in his butterfly walks.

In 2019, Smith was granted honorary citizenship of Nepal. “There wasn’t anything for me to do in England, while there was something for me to do here,” he says as he takes out his citizenship certificate from inside a worn white bag.

Although he had always wanted to be a Nepali citizen, being one took him a long time. He had applied as far back as 1995, but it was only years later, after Surendra Pariyar pulled in all possible efforts, that the Nepal government finally responded to the request.

“The man wants to live out his life here, be cremated and have his ashes scattered in the Seti, so he deserves to be a Nepali,” says Surendra.

The last time Smith left Nepal was to go to England in 2006. His brother lives in New Zealand and he hopes he could go there once to visit, but admits that at his age, travelling is difficult.

Smith finishes up his toast and an omelette, which Min Bahadur’s daughter brings him. He places leftover scraps of eggs down on the floor and says, “This is for the बिरालो.”

Then Putali Baje stands up, the white bag clutched in his hands, and slowly makes his way back inside his little green house.

writer

Shristi Karki is a correspondent with Nepali Times. She joined Nepali Times as an intern in 2020, becoming a part of the newsroom full-time after graduating from Kathmandu University School of Arts. Karki has reported on politics, current affairs, art and culture.