Looking ahead to Nepal’s 2027 elections

Time running out to pass the electoral reform Bill so the next polls are free, fair and inclusiveThere is less than two years to go till elections to all three levels of government, and Nepal’s major political parties are gearing up to engage voters.

The governing UML has launched its ‘Mission 2084’ campaign, but the party is being rocked by former president Bidhya Devi Bhandari's effort to join the electoral fray.

The UML’s coalition partner, the Nepali Congress (NC) is wracked by rival contenders arguing over whether to hold its general convention before or after the next polls.

The opposition Maoist Centre is on a nationwide grassroots tour to rebuild its support base after it was ousted from the UML-Maoist coalition last year.

The leaders of the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) in a strategic move are mobilising the diaspora to vote for the party symbol, bell, or influence family members back home.

RSP lawmaker Sumana Shrestha recently addressed Nepalis living overseas, urging them to participate in the next election.

‘Save your time off, save your money, and come back home in 2027 — either to run for one of the 36,000 elected positions, or support those who are running for office,’ Shrestha said. ‘But whatever the case, you must come back to vote. Let’s ring the bell in 2027.’

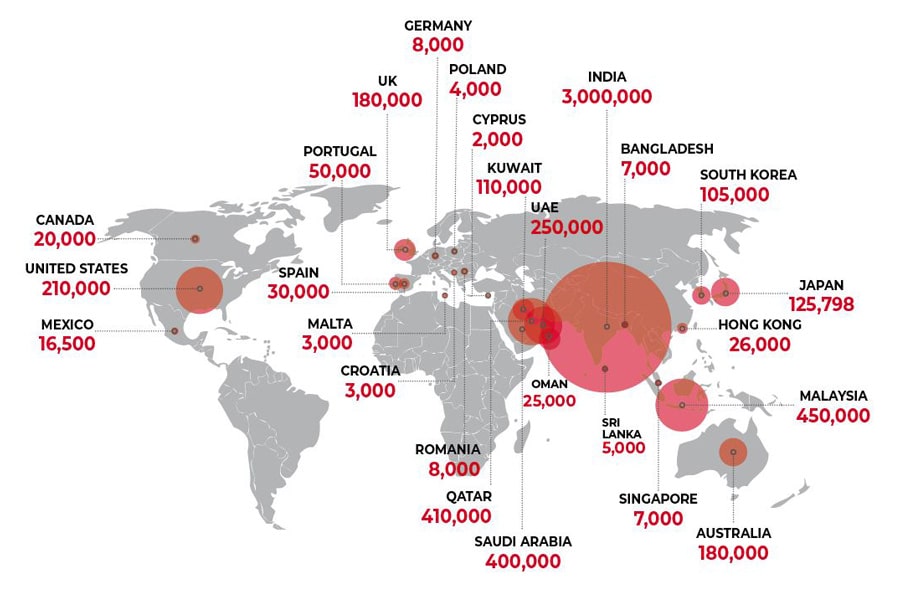

Overseas Nepalis emerged as an important bloc during the 2022 election because they convinced families back home to vote for new independent candidates, not established party nominees. RSP hopes to cash in on this anti-incumbent protest vote again.

The census put the country’s absentee population at 2.1 million, but experts say it is at least double that. Most are in the 20-35 age group, and disillusioned with Nepal’s serial leaders. Social media platforms allow them to be apprised of goings-on in Nepal, which means those living and working overseas are actively engaged in politics back home.

This week, the judiciary’s judgement implementation directorate, in response to an application from lawyers associated with the RSP, sent a reminder to the Election Commission to act on the Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling to guarantee Nepalis overseas their constitutional right to vote.

The Election Commission itself in 2023 registered the Bill to Amend and Consolidate the Election Law proposing various amendments including out of country voting, but the Bill has been idling at the Home Ministry for two years because of lack of support from the three main parties.

“The state and the Election Commission have been lethargic in taking action to ensure rights for out of country voting,” former Chief Election Commissioner Bhoj Raj Pokharel told us.

Ensuring out of country voting rights is not a new idea. During the 1980 referendum on the Panchayat system, some embassy staff and officials abroad were allowed to vote. And the Election Commission floated the idea in 2008, but that did not go anywhere.

It is not just opposition from mainstream parties that has prevented voting by mail. There are also legal, financial, and technical challenges.

“In principle, we expect that our political leadership wants as many people as possible to exercise their franchise and participate in the political process,” says Radhika Regmi Pokharel of The International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES).

But, she adds, “In reality, if the leadership thinks absentee voting might jeopardise their chances of winning, they will be less keen on carrying out electoral reforms.”

Nepali students, migrant workers, and people holding long-term residency permits are scattered across the world. It will be a challenge to set up voting booths at multiple points beyond embassies and consulates during elections, especially without bilateral agreements in place to designate spaces for polls.

Nepal’s mixed first-past-the-post (FPTP) and Proportional Representation (PR) electoral system also means that conducting elections at a Nepali Embassy for example in Qatar where there are hundreds of thousands of Nepalis will be complicated, Pokharel explains. There are Nepalis from multiple constituencies in a host country, and FPTP ballots are different for each constituency, while PR voting only requires a single ballot.

“We can at least conduct PR elections overseas, but that does not ensure complete electoral justice,” adds Pokharel. “The problem lies in implementing electoral laws in a way that ensures overseas voters can exercise their franchise.”

Experts say some pilot schemes for overseas voters can be started in select embassies where feasible.

“Even if we are not ready, the least we can do is to make sure that Nepalis abroad, in particular overseas migrant workers, are registered to vote, be it through Nepali embassies of the countries they are based in, or when they leave Kathmandu airport, or at points along the Nepal-India border,” says Gopal Krishna Siwakoti at the Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL).

Whether or not they are able to vote, overseas Nepalis will nonetheless be influential in upcoming elections. “Nepali diaspora, especially those who are settled permanently abroad will influence voters here in Nepal to some extent even if they are loyal to a particular party,” adds Siwakoti.

But it is not about guaranteeing voting rights just for those abroad, all eligible voters within Nepal must also be allowed to vote in the place of their domicile and not make a journey back to their districts.

“There is a lot of talk about out of country voting, but how about in country voting?” asks Regmi.

At present, Nepalis cannot vote from their current place of residence. Only election officials and security personnel can cast at least their PR ballots from where they are stationed.

Internal migration and inability to leave work means many cannot travel to their constituencies for election day. Some candidates therefore spend money to bus voters to their constituencies to vote.

While Nepalis have historically shown great enthusiasm at election time, the need to travel to vote combined with increasing apathy towards traditional parties, means turnout declined from 78% in 2017 to 62% in 2022.

Early voting, mail-in ballots, fixed election dates, and facilitating electronic voting would make it easier for people both within and outside the country to vote. But mail-in voting will depend on the postal system, which is not reliable, and online voting may also have security challenges, both domestic and geopolitical.

Most of all, facilitating all these different methods of voting will require significant costs. “Ultimately, democracy does not come cheap, and we have to invest in it,” says Regmi.

Meanwhile, the governing UML-NC coalition has been debating constitutional amendments to reform the mixed election mechanism, an agenda they had hinged their partnership on when they formed their alliance last year.

Nepal’s political leadership has long maintained that the country’s mixed electoral system does not allow for one party to form a majority, only coalition governments, which has made governance and politics in Nepal unstable.

Coalition leaders say they want to amend the Constitution to ensure political stability by ensuring members of the House of Representatives are elected through the FPTP system, and members of the National Assembly are chosen through the PR method.

However, experts say it is not so much the electoral system but governance and political leadership that are responsible for high government turnover and instability. They point to countries like Japan, Switzerland, and Germany which have stable politics despite having a similar mixed electoral scheme.

Inclusive, Diverse

“Every electoral system has its unique characteristic, there is no one perfect system," says Pokharel. “An electoral system does not guarantee stability, that is up to the drivers of our state mechanism.”

The proposed amendments risk rolling back the quotas and reservation that currently guarantee the representation of women and Nepalis from underserved communities in national politics.

“FPTP has become costly, and women and minority communities simply do not have the resources and network to compete with other candidates in more privileged positions,” says Regmi. “Currently proposed amendments will deal a heavy blow to inclusivity and diversity in governance.”

Promises of electoral reforms have not materialised into concrete plans of action. And with just two years to go for 2027, it will be difficult to organise out of country voting or modify the mixed electoral system — even if Parliament passes relevant laws.

“It is too late now to successfully set up the relevant infrastructure and systems overseas in time for 2027,” says Regmi.

Pokharel concurs: “They need a two-third majority in Parliament to successfully amend the Constitution. Barring a miracle, I don’t see a possibility of election reform before 2027.”

writer

Shristi Karki is a correspondent with Nepali Times. She joined Nepali Times as an intern in 2020, becoming a part of the newsroom full-time after graduating from Kathmandu University School of Arts. Karki has reported on politics, current affairs, art and culture.