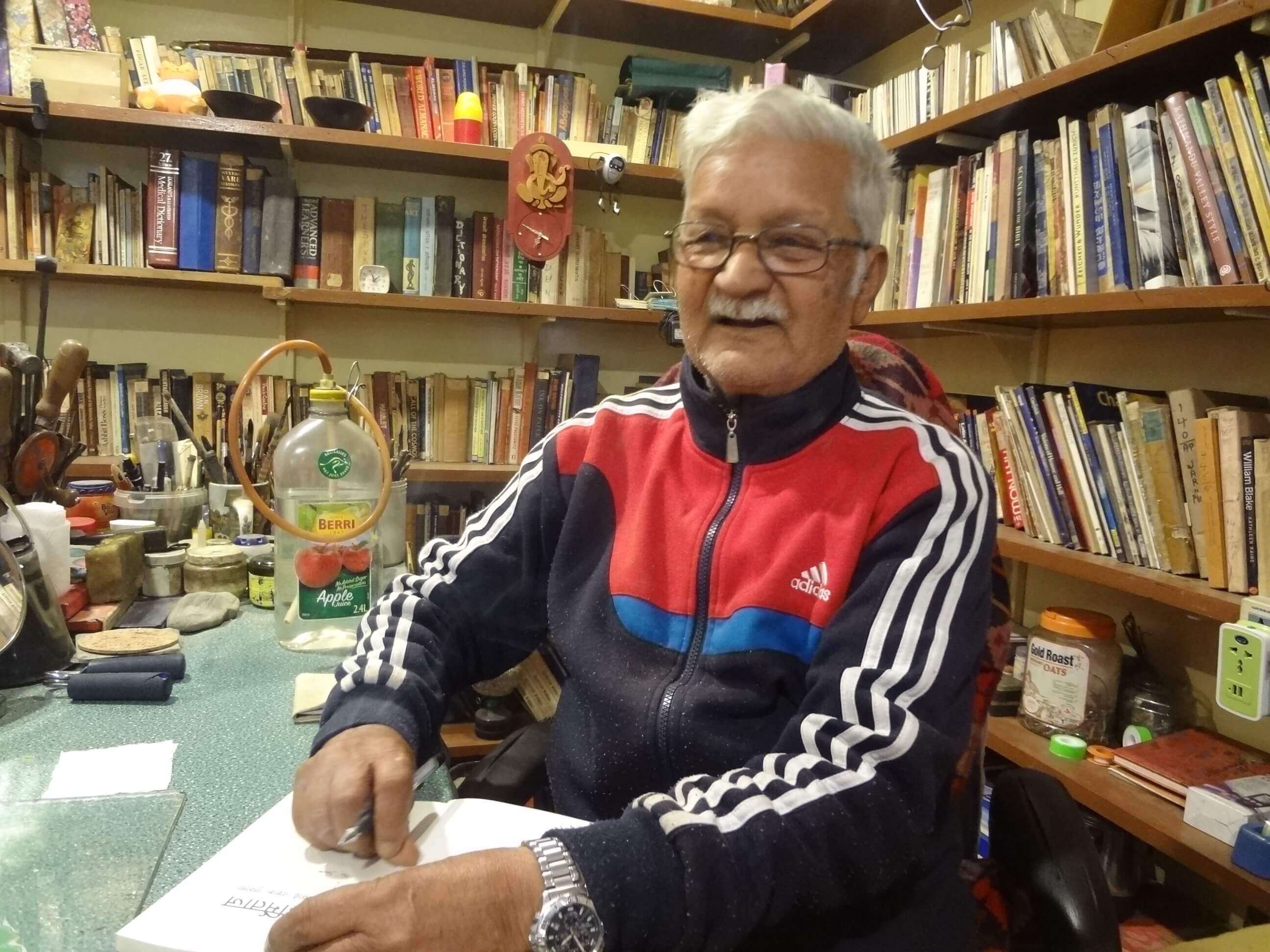

Manujbabu Mishra's expression

Manujbabu Mishra had lived the second half of his life in almost complete isolation, not going outsidehis leafy home on the outskirts of Kathmandu. His studio, cramped with books and painting equipment, suited his lifestyle and personality.

His large writing desk is lined with containers, each holding tools of an unimaginable variety: hammers, wrenches, screwdrivers, scissors, brushes. He was skilled with his hands, and made his own bamboo pens, a water cannister to sip from, and even crafted his own chairs, benches and easels when younger.

Before advancing age and ill health forced him indoors, Mishra lived a hermit's life in an outhouse while his family lived nearby. The fiercely self-sufficient artist,who preferred expression to aesthetics, passed away in his sleep at the age of 83 on 8 August.

Mishra's residence, fittingly called 'Hermitage,' reflected his artistic sensibilities: an old fashioned pulley bell instead of an electric one, sea shells adorned the slot for his letterbox, artistic pieces from all over the world litter his home.

He disliked uniformity and conformity, and this is reflected in the ambience of his studio decorated with multicolored warm rugs and a library beautifully age-worn. Everything is exactly where he left it, including a half-finished painting.

Mishra was known for a grotesque trademark style where his own face is seen in distorted forms, often accompanied by horns, tridents and rockets amidst tumultuous multi-coloured clouds swirling over transgenic animal forms. He imbued each of his symbols with meaning.

The trident is a symbol of power, of creation and destruction, which to him symbolised eastern philosophy. The horns are often seen growing out of his own self-portraits, and are emblematic of the beast in the man. He often bemoaned that modernity seemed to isolate people even further from each other, which was increasing these ghastly tendencies.

Even though he almost never left home, he painted portraits of our times with a deep understanding of the devastation outside: of nature, of humanity, of morality and goodness, of loneliness and the fear of isolation. There is a loneliness and isolation in Mishra’s studio, accentuated by his absence.

"There is a lot of demand for a certain types of images from Nepal," he would say. "Paintings of mountains or lifestyles. I would have been rich by now if I had painted those. Beauty is not everything in art. The scream of people who are injured in war, that makes a powerful piece of art too. And my art is expressive and emotive rather than aesthetic." He sometimes described his paintings as "shit",an excretion produced when he got a great urge to empty his emotions.

Also Read: The face of faceless art

The rocket streaking across many of his paintings were a symbolic protest against the global dominance of Western civilisation. He was not just an artist but also a chronicler of world art history, and was concerned about how colonialism had slowly wiped away the cultures of Africa and Asia. A fervent admirer of ancient Egyptian art, he claimed that no statue made after Nefertiti is comparable for quality.

He was a lifelong seeker of original Nepali styles which he believed to be more vibrant than the 'monochromic wash' of the western palate. He opened an informal art school at his home where he would take in only janajati students, hoping they would create art that reflected their cultures. That, however, did not last long as students from all ethnicities wanted to enroll in his class, and the numbers grew too large for him to handle.

It seems ironic then that this seeker of Nepaliness in art himself used a western genre. After graduating from the College of Arts and Crafts in Dhaka in 1969, he was among the early pioneers of modernism in Nepali art. Asked to explain the contradiction, he once said he was forced to do so because it is not possible to paint in completely Nepali style today.

However, he lovingly preserved a small painting of his father by the famed Nepali painter Anandamuni Shakya, which he would show as an example of Nepali style art to anyone who was interested. This week, it still hung on the wall outside his studio.

Also read: Empowering expressionism

Missing a creative curator, Kanak Mani Dixit