Not poor, but not rich

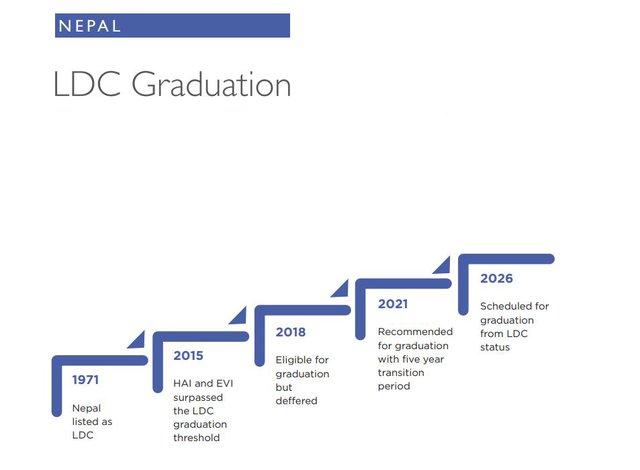

LDC graduation is a stepping stone for Nepal’s development, but a better investment climate would helpNepal is graduating to become a developing country on 24 November 2026 after half-century in the Least Developed Country (LDC) category. By 2030, the country hopes to transition to middle-income status.

Everone from Prime Minister K P Oli have boasted that this is a matter of national pride, and will have a multiplier impact on trade and economy.

But will it make any difference to the average Nepali? Not unless improved governance spurs investment and creates jobs.

Countries need to meet at least two of the three criteria in two consecutive triennial reviews to be eligible for graduation from LDC. Nepal has consistently met the thresholds for the Human Assets Index (HAI) and the Economic and Environmental Vulnerability Index (EVI) in 2015, 2018, and 2021. But Nepal was recommended for graduation before meeting the per capita Gross National Income (GNI) threshold of $1,306.

“A major implication of LDC graduation is the loss of preferential market access available through Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) and other arrangements,” explains economist Sameer Khatiwada. “But over two-thirds of Nepal’s exports are to India, and the preferential market access to India is through a bilateral trade agreement. This has nothing to do with our LDC status.”

Furthermore, a provision under the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) allows Nepal to export to India duty-free if the items are at least 30% value-added. Nepali traders take advantage of this by re-exporting edible oils without meeting that requirement, falsely boosting Nepal’s exports.“

Following graduation from LDC, the value addition threshold might increase to 40%,” says Kalpana Khanal of the Policy Research Institute. “This is supposed to work to our advantage, because on paper value addition inherently means job creation at home.”

But Nepal’s exports to other major destinations will face tariff increases with the graduation. A South Asia Watch on Trade, Economics and Environment (SWATEE) study shows that while tariff increase in the US market is relatively low (see page 5) it is considerably higher in Europe.

The International Trade Centre (ITC) in a 2022 study also estimated that graduation could result in a 4.3% decline in Nepal’s projected exports, but this is excluding the impact of changes in ‘rules of origin’ provisions in preference-granting countries such as the UK and Europe.

Nepal’s top export to these preference-granting countries is carpets, and will not be impacted, but other items such as textiles and apparel will be heavily affected due to higher cost of production. The impact will felt mostly by small and medium enterprises which represent the largest share of exports to LDC-specific preference-granting countries.

As for the service exports, Nepal never really made use of the World Trade Organization’s LDC services waiver anyway, hence the effect will be minimal, if any.

There is also concern about Nepal’s graduation at a time when the global economy is topsy-turvy, amidst tariff wars and conflicts. This affects Nepalis abroad directly and may impact remittances which hit $11 billion in 2024. In comparison, Nepal only received $350 million in foreign loans and grants last year.

Tourism arrivals have finally reached pre-pandemic levels, but bad publicity about pollution, poor infrastructure and bureaucratic hurdles hinder further growth. Manufacturing continues to struggle, while hydropower and the IT sector have taken off.

“Look at data -- tourism arrivals are up, spending is up, IT exports are up, EV sales are up, Europe still needs 85-90 million skilled workers. We are sitting on $16 billion in cash reserves, our balance of payment, foreign exchange reserve, tax to GDP ratio, credit flow are all positive, we have to build on these factors,” says Sujeev Shakya of the Nepal Economic Forum.

He adds: “Our mindset creates negativity to promote rent-seeking behaviour, but this cynicism will go away after 2026 with LDC graduation. We must deal with data, look at trends, and projects which will bring in international investments.”

Khanal agrees that investment is not dependent on LDC status. The factors that that affect investment are policy stability, a strong legal framework, market potential and ease of doing business. She adds, “That is where our focus needs to be, and we need to retain Nepalis with jobs at home for our sustained growth.”

After 2026, financing support from donors and aid agencies could be affected and Nepal will no longer be able to access Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) to adapt to the impacts of climate change. But the Global Environment Fund and Green Climate Fund will still be available.“

LDC status does not determine bilateral development aid, that is usually driven by broader geopolitical considerations,” says Sameer Khatiwada. “The World Bank and Asian Development Bank, which provide concessional loans to Nepal, it is determined mainly by per capita income, not LDC status.”

However, Nepal may lose some concessional terms for loans. Nepal is currently a lower-middle-income country as per the World Bank in the bracket for GNI between $1,036 and $4,045.

The country is already receiving more loans than grants and in July the World Bank increased its interest rate on loans by 100% from 0.75 to 1.5%.

“All this means that the impact of LDC graduation for Nepal might not be as earth-shattering as some tend to think. Countries that have recently graduated, such as Botswana and the Maldives, have shows that graduation is just a step in a country’s development path,” says Khatiwada.

Sujeev Shakya also sees the glass as half full, explaining that LDC graduation is just a stepping stone if Nepal has the right policies in place. He adds, “Nepal’s biggest advantage is our working age population and we have investments coming in. These aided by how adaptive we are as a society are the very foundations on which Nepal will grow.”

This Editorial is brought to you by Nepali Times, in collaboration with INPS Japan and Soka Gakkai International, in consultative status with UN ECOSOC.

writer

Sonia Awale is the Editor of Nepali Times where she also serves as the health, science and environment correspondent. She has extensively covered the climate crisis, disaster preparedness, development and public health -- looking at their political and economic interlinkages. Sonia is a graduate of public health, and has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Hong Kong.