Vipassana during a revolution

Inside, we focused on our breath. Outside, the nation held its. This is what we found when we finally exhaled.One Friday night last month, we were swapping stories about Vipassana, a rigorous meditation technique of silent observation, over dinner. We spoke of its ten days of noble silence, of respiration, observation, and sensation.

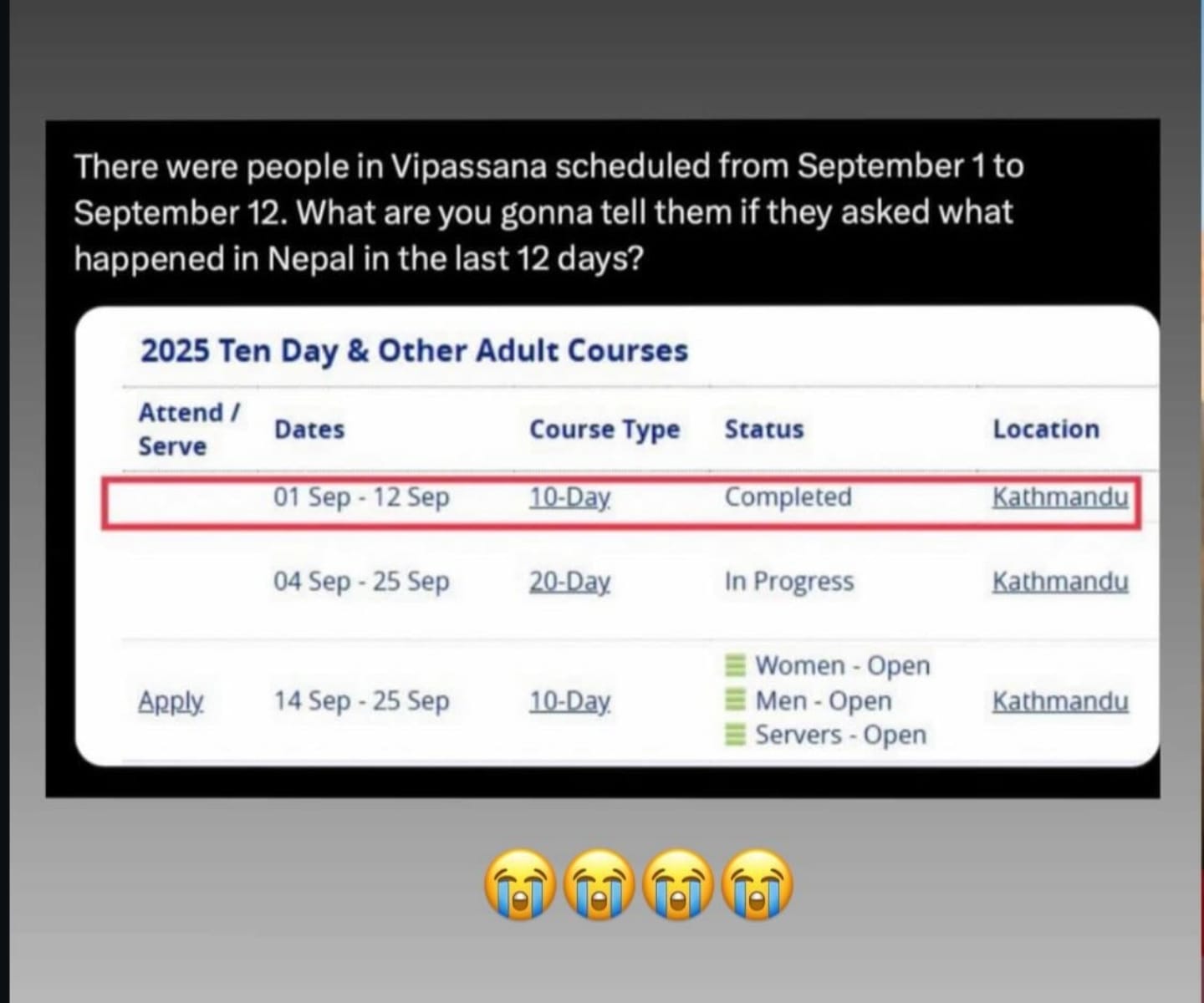

I told them about my first retreat in Lumbini last year when my mind kept getting distracted: ‘What is happening in the outside world? Is K P Oli still prime minister? When I emerged ten days later, he was still PM.

During my second Vipassana in February this year, I reassured my mind that nothing dramatic could unfold in ten days. Still, my gut knew this country was always one headline away from revolution. By my third retreat, I was confident, even cocky.

At that dinner, I joked: “What could possibly change? If Oli survived my first two meditation retreats, the world can hold steady for a third.”

I should’ve known better. On 1 September, I was back at Shivapuri for the second time, my third retreat, with no expectations — only hope that ten days of noble silence would peel yet another layer from my mind.

Vipassana is a paradox: brutally difficult, yet infinitely generous. It is the tool needed to tame and know your unconscious mind, and to know yourself even a little through it is a profound achievement.

My room at Z House had the best view of the Kathmandu Valley. I developed a ritual: press my hands against my cheeks and stare down at the city. The city below looks chaotic, but somehow beautiful in its stubbornness, where pollution and pride coexist. From up there, it looked like no one was free, trapped in their egos, pettiness and misery.

Then, softer thoughts of Metta and compassion would emerge. If only every single person could sit in silence and know their breath, just once. Blessed with ten days of Dhamma teachings on universal law, I imagined our 334 patriarchal parliamentarians and the Oli, Deuba, Prachanda trinity.

UNSEEN CHAOS

On the seventh and the eighth days of Vipassana (8–9 September) there was black smoke rising from the Valley below. Why were people burning all that garbage? There was no traffic on the straight road down from Budanilkantha. There were gunshots, and I assumed locals were shooting at marauding monkeys. I mistook the sound of helicopters at night for flights circling after takeoff.

On the ninth day and in the morning of the tenth, it rained heavily. I tried to spot Dharara like I did every day, but the city was shrouded in a blanket of thick black smog. Even after two days of heavy rain, the smoke had not been washed down. This did not make sense, but my mind had returned to the safe harbour of my meditation. Nothing to see here.

On the morning of 9/11, the tenth day, as we emerged from silence, the hall outside filled with chatter. Many people left, weeping, overwhelmed by the experience of the past ten days. We joked about our hardships and dreamt of delicious food, feeling a wave of accomplishment after a documentary about how Vipassana had transformed Tihar Jail in New Delhi.

The hall radiated with inspiration and hope. Then, as the film ended an assistant teacher made an announcement: “There are serious protests going on in the Valley. K P Oli has resigned as prime minister. There are no cabinet ministers. The military has taken over, and a curfew has been imposed.”

The news hit like a lightning bolt. Mental tranquility gave way to gasps of “What the f**k?” In the main Dhamma Hall, some women erupted in applause. We had spent ten days cultivating Metta, only to step out and realise the world had erupted into chaos.

We huddled, trying to piece together fragments of what was happening. The Valley was still covered in black smoke, the main road was still quiet. A neighbour turned up the radio, reporting deaths, destruction and curfew.

A first-time meditator, Shivani Karn, overheard a neighbour from wall cross telling his son that people had been shot and that he should not go to school any more. She had wanted to flee the Centre, but stayed on.

Stranded foreigners from Argentina to China were bewildered and terrified. Volunteers debriefed us, recounting the shocking details: buildings burning, ministers’ houses ransacked, Oli fleeing, Deuba and his wife beaten up. The leaders were all in the Shivapuri barracks up the mountain. Over 15,000 inmates had broken out of prison. It was a catastrophe unfolding in real time. The city felt ripped out from a nightmare.

In the common space, people complained about corruption and the ban on social media. But an understanding emerged: both those in power and those who grant it are bound by the law of cause and effect.

Driving down from Shivapuri on the morning of 12 September, my heart sank. The smog I had seen was smoke from still smouldering buildings. It was not garbage burning, but the rage of the people. Those were not people scaring away monkeys, but guns that killed innocent lives. The sound of aircraft were actually helicopters rescuing politicians.

We drove past Singha Darbar, a charred ruin. Another Vipassana meditator, Anjali Baidya, shared a chilling memory. She recalled being 12 years old in 1973, watching from her home in Makhan Tole as Singha Durbar first caught fire. History had repeated itself 52 years later.

One Bhatbhateni supermarket after another were scorched, police stations, government offices, once symbols of everyday life. There were soldiers everywhere, not police. Amidst the devastation, a deeper truth settled in. This, too, was Anicca — impermanence.

Anicca teaches us that all things are constantly changing, including our thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations. Political systems, power structures, national crises are all transitory. This understanding is crucial for healing. When we cling to the idea that a leader, political system or ourselves are permanent, we set ourselves up for disappointment and anger when it inevitably changes.

The Dhamma teaches that responsibility is shared. The anger and fear on the streets are similar to feelings many carry inside. We Nepalis have intergenerational trauma. What I saw was not an abstraction: the gunshots and chaos echoed the terrifying nights of 1 February 2005 in Panauti, a grim replay of the fear I knew as a child at Malpi school, huddling with friends for safety.

Read also: What next, Nepal?, Shristi Karki

Our national history is a series of ruptures that become personal landmarks. I was nine years old at my aunt’s birthday party on 1 June 2001, when the celebration was abruptly called off and we were sent home into the silent shock of a royal massacre.

This pattern must be broken, and it starts now. The path to national healing must begin with individual healing. We can learn from the story of Angulimala, a violent figure who was transformed by the Buddha’s compassion. The Buddha walked steadily toward him and said, “I have stopped, Angulimala. You must stop too.” Angulimala realised the truth, renounced violence, and was enlightened.

Cycles of anger and conflict can be softened and transformed. Nepal’s long-term well-being depends on our ability to approach the Dhamma as a pragmatic tool. Inner calm can help us process collective trauma. By cultivating forgiveness and compassion, we can create a stability that begins within. True healing begins when we stop externalising our pain or intellectualising our emotions, and start nurturing our own inner peace.

As the dust settles, the true noise begins: the roar within. We are left with a stark choice: remain trapped in this endless loop of rage, or we can deliberately choose to stop. The Dhamma is not some philosophy for a meditation centre; it is the raw truth of our applied wisdom.

Sushila Karki, Nepal’s first female prime minister, may have emerged as a new ‘messiah’ but we must begin to take responsibility and accountability. Change cannot come from chaos, it is a conscious effort we must make precisely when it feels most impossible.

The path forward is not through the streets, but inward — into the ruins of our own self-righteousness. The disparity and deep-seated grudges are the quiet kindling that have brought this new revolution. The rage on the streets is about suppressed dignity, and a burning hunger for justice.

It is time to check the recesses of our minds and hearts, sit down, breathe, and to ask: “When do we stop running, and when do we start healing?”

Alisha Sijapati is a writer specialising in cultural heritage, and a former Nepali Times correspondent.