Going native at COP30

Indigenous peoples demand access to climate finance as world falls short of delivering on promisesThe Madi River in Nepal flows down from the Annapurna range on which there are four hydropower plants being built in a cascade.

One of the schemes displaced the indigenous Gurung people from their ancestral land in the once-thriving village of Chansu.

There are many other Chansus across Nepal where infrastructure projects have forced local communities from the land of their forebears. Many have been relocated to sites which are vulnerable to landslides, floods and extreme weather as a result of climate breakdown.

Halfway around the planet from Chansu in the Brazilian city of Belém at the gateway of the Amazon, Nepal’s delegation to this year’s COP30 climate summit is hoping with other developing countries to negotiate a deal on being compensated for loss and damage from climate-related disasters.

Nepal’s delegate spoke also on behalf of Bhutan and Bangladesh to present a joint position, emphasising that the survival of the planet hinges on the fulfilment of the 1.5°C goal, urging nations to revisit the 2035 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to reduce their emissions to bridge the gap between ambition and implementation of global climate commitments.

But even as countries negotiate their climate commitments at global fora like COP30, indigenous communities continue to be at the bottom of the priority list.

The sixth edition of The State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples reveals a stark imbalance: although indigenous peoples make up just 6% of the global population, they safeguard 80% of the planet’s remaining biodiversity. All the while, native communities receive less than 1% of international climate funding.

For its part, Nepal has improved on its second Nationally Determined Contributions to make its NDC 3.0 more inclusive of indigenous and underserved communities. At least 60% of Nepal's forests will be community-run by 2035, with operational structures consisting of 50% women, and proportional inclusion of Dalit and indigenous people in key management positions.

NDC 3.0 also ensures that women, local communities, and Indigenous people get fair and equitable benefits from sustainable forest management and biodiversity conservation. Additionally, local and indigenous knowledge of climate change mitigation and and their cultural heritage is set to be fully integrated into school curricula in the coming years.

This progress has been possible through continued efforts and advocacy from native communities, but the conversations were far from easy, and those in-charge of making decisions were not entirely open to feedback, experts say.

“For those with indigenous knowledge it was difficult to participate in talks — from handling technology to understanding the jargon of policy,” says Tunga Rai, Director of the Climate Change Program at the Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities. “At times our participation felt superficial, it was indigenous washing.”

“Our concerns were not easily accepted, we faced challenges in encompassing issues of land and territories into the climate action process,” she adds.

Indigenous people make up more than 35% of Nepal’s population, and are limited to the role of spectators in climate action efforts, activists say. They still do not get seats at the decision-making tables. Nepal’s delegation at COP30 does not have a single member from an indigenous group.

This is not just limited to Nepal, native peoples are being neglected at the world’s biggest climate platform — from the foothills of Himalaya to the forests of the Amazon.

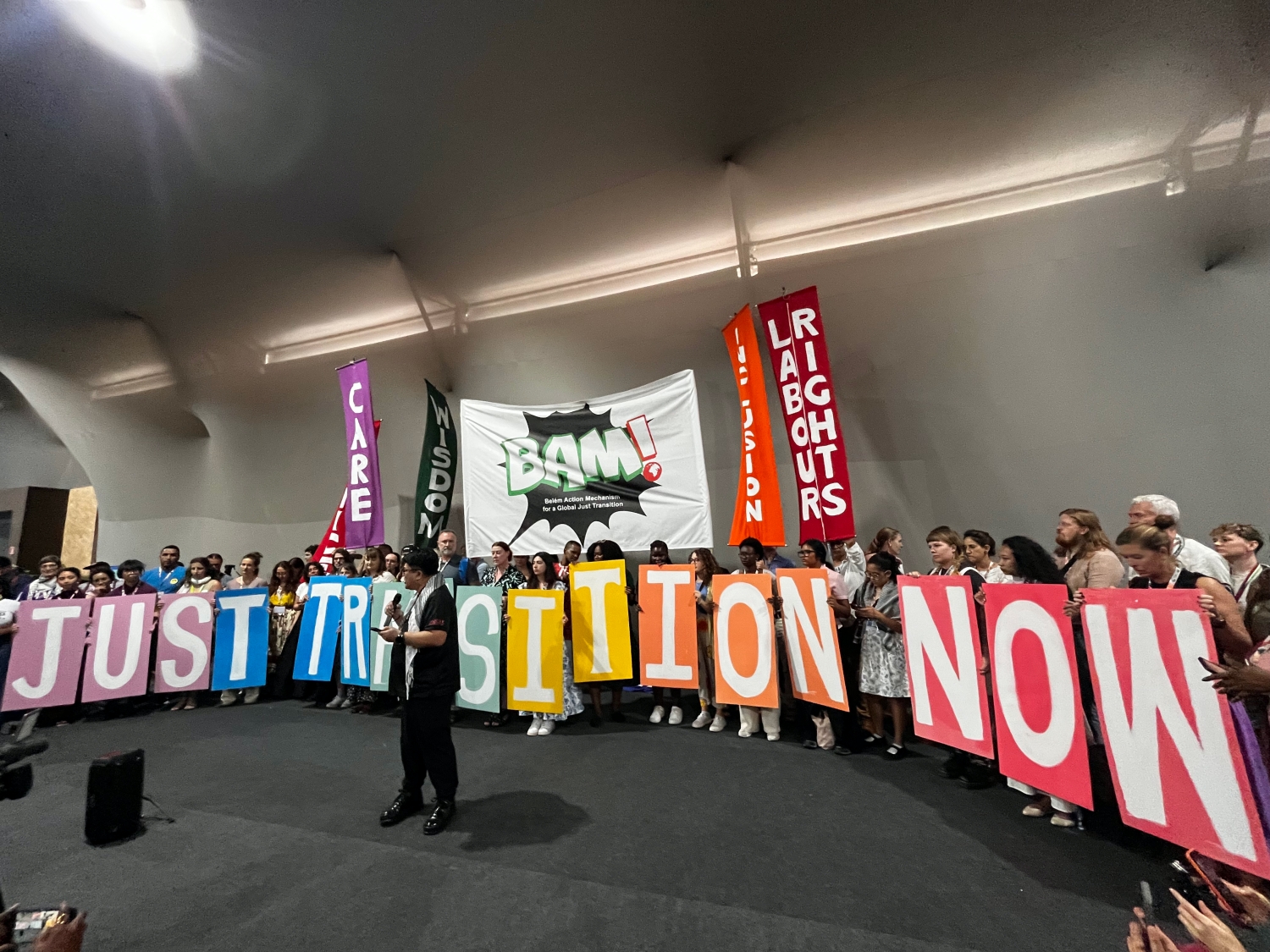

Indigenous groups from Brazil and the region are making their voices heard in Belém, after failed expectations from local communities that climate issues important to native peoples would gain greater attention at the heart of the Amazon. On the second day of the conference, members of the Tupinambá community blocked the main entrance of the COP venue, declaring: “Our land is not for sale.”

Ketty Marcelo Lopez, president of the National Organisation of Indigenous Andean and Amazonian Women of Peru points out that Indigenous communities have always been at the forefront of the climate crisis

“As we move forward with Nationally Determined Contributions, indigenous rights have not been protected,” says Daria Egereva, of the Center for Support of Indigenous People of the North (CSIPN). “Indigenous rights must not be limited to documents, but also reflected in real steps.”

This year, the most climate-vulnerable countries are demanding that the Loss and Damage Fund be expanded to $1.3 trillion. At the same time, indigenous people are demanding proportionate access to climate financing, urging authorities to ensure that climate action funds reach the people most impacted by the climate crisis.

But climate finance negotiations at COP have more often than not been defined by developed nations manipulating deals at the expense of developing nations.

Gideon Sanago, an advisor at the Santiago Network, urges communication and collaboration between Indigenous communities and policymakers so that climate financing is easily accessible to Indigenous communities.

Meanwhile, indigenous leaders like Onel Inandinia say that the Global North must facilitate access for the Global South in ways that support native peoples, integrate native communities into climate financing, and create Indigenous-led funds.

This story was produced as part of an Internews Earth Journalism Network and the Stanley Center for Peace and Security fellowship.