Dhanyavād, Subhāy, Guruju

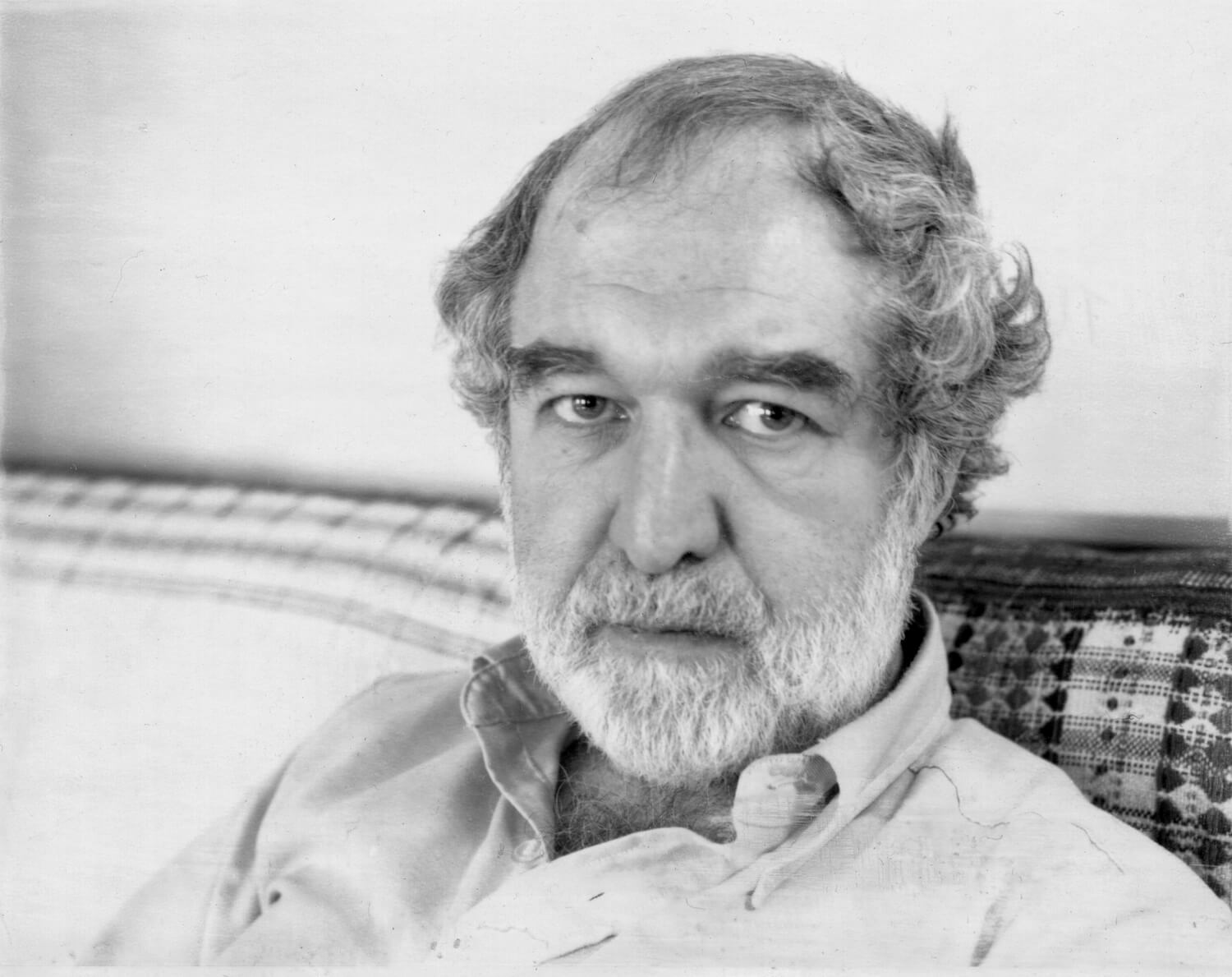

Ted Riccardi often recounted the story of turning his attention to Nepal, and pursuing the career that followed as a series of fortunate accidents. Disappointed with his chosen field of study in law, a chance encounter with a teacher from his high school ultimately led him to become the prominent scholar of Nepal that he was.

Though it was my first trip to Nepal that shifted my attention from Latin America to the Kathmandu Valley, I am somewhat embarrassed to acknowledge that it was by accident that I happened to meet Ted, who ultimately made my studies there and so much more possible.

I received the letter informing me of my acceptance into the graduate program in anthropology at Columbia University while visiting Kathmandu as a backpacking tourist. Presumably I was accepted, at least in part, on the basis of my proposal to pursue applied anthropology in Latin America. But by the time I accepted their offer to join the program, my heart and mind were set on conducting research in Nepal.

It was only through a chance perusal through the ‘Ns’ in the course catalogue after arriving at Columbia that I discovered Nepali was being offered there by one Professor Riccardi, who was oddly ensconced in the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures.

I immediately went to his office in Kent Hall and asked if I could study with him. He seemed a bit surprised and inquired about the basis of my interest, and, perhaps detecting that I was afflicted with a nascent love of Nepal that he thought would grow with proper feeding, he allowed me to join Bill Fisher in the one Nepali class he was teaching at the time, even though Bill had started the year before.

I am sure Bill was a bit dismayed at my joining the class as a neophyte, but he seems to have gotten over it, and has become one of my dearest friends: another of the countless gifts Ted has bestowed upon me.

To teach me Nepali was an enormous gift, all the more so because of Ted’s stunning proficiency in it. While doing my doctoral research in the early ’80s, I once returned to my apartment in Patan to be greeted by the son of my landlord with a note. When I discovered that it was from Ted, I excitedly told him that it was from my guru, and he asked, “Is he Nepali?”

Clearly the young boy was experiencing cognitive dissonance, Ted’s appearance not being consistent with his speech, but his speech being without accent, and so fluent that only his being Nepali could account for it.

I often think of how torturous it must have been for someone so gifted as he to attempt to impart his knowledge to the likes of me. Even though his Nepali was better than that of many Nepalis, partly due to a series of fortuitous events in his own life (see Don Messerschmidts’ article in ECS from July of 2010), Ted insisted that his students also work with a native speaker from Nepal. And so it was that Kanak Mani Dixit came into my life, as he was at Columbia studying journalism at the time: another gift beyond measure.

The point of these stories, which may seem to focus overly on me, is that Ted was extraordinarily generous with his knowledge, patience, and time. He was also generous in sharing his many friendships and connections with people in Nepal.

It was through him that I also came to know Mohan Khanal, Prayag Raj Sharma, and Dor Bahadur Bista before I ever went to Nepal to do my research, all of whom came to New York through his efforts. Once in Nepal, the mention of his name inevitably brought smiles, inquiries about his welfare, and generous hospitality.

It was from Ted’s house in New Delhi, where he was cultural attaché at the time, that I launched my doctoral research in Nepal. It was only with his support that I was able to pursue my research in Nepal for nearly three years, and only with his patient encouragement that I was able to complete my dissertation four years later.

The most generous among us do not draw attention to their generosity, but rather somehow allow one to come to expect it without realising it, and do not seek thanks for it. Though I have tried over the years to express my gratitude to Ted, in putting these words to paper I realise how futile a task that was and is.

Bruce McCoy Owens is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Wheaton College in the United States, and has studied and documented the Rāto Matsyendranāth tradition of Kathmandu Valley.