Warning: breathing is hazardous to health

New report says Nepalis could live 3.3 years longer if air pollution is cleaned upAn average Nepali could live 3.3 years longer if air pollution is reduced to meet the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline, according the annual Air Quality Life Index 2025 published this week.

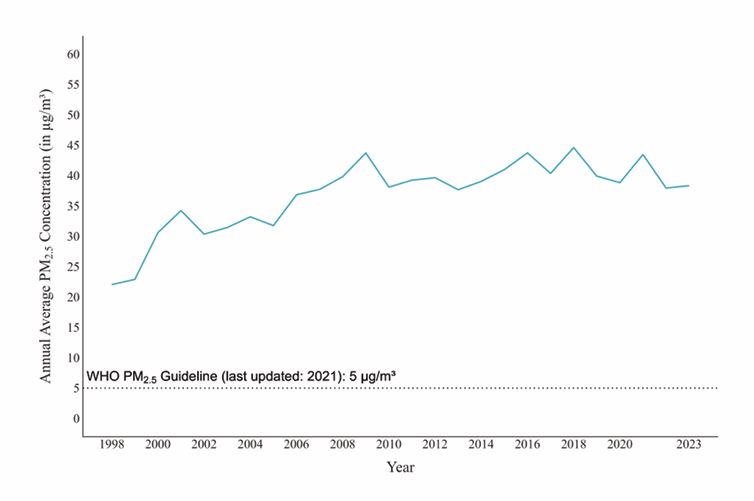

The annual average concentration of tiny suspended particles in the air (PM2.5) in Nepal in 2023 was 38.3 μg/m3, nearly eight times the WHO standard, and 10% higher than 2022. Thirty years ago, air pollution in Nepal was half the current levels. WHO says particulate concentration above 5μg/m3 is hazardous to health.

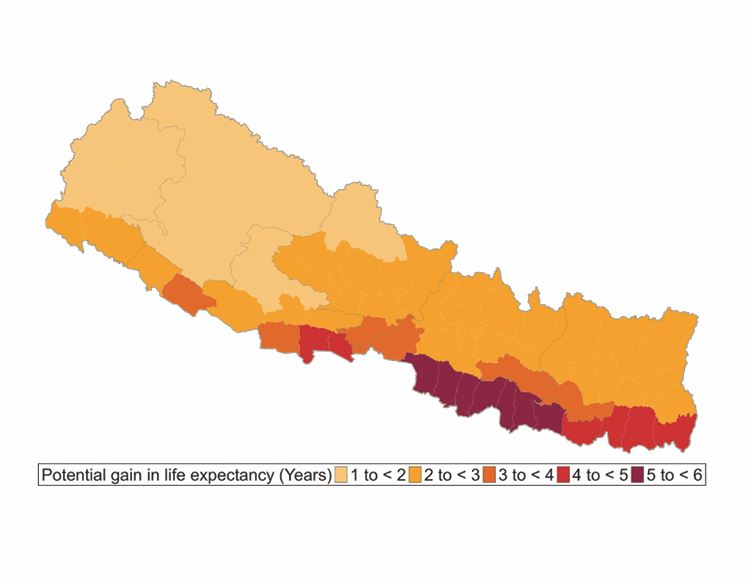

The most polluted parts of Nepal are along the Indian border in Rutahat, Mahottari, Dhanusha, Parsa and Bara districts in Madhes Povince where average life expectancy is reduced by as much as 5.3 years.

People in Sarlahi, Siraha, Saptari, Morang, Sunsari, Rupandehi and Jhapa are also dying at least 4 years earlier. The Air Quality Index 2025 report which is published annually by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago, says the figure is relatively lower for Kathmandu and Lalitpur at 2.6 and 2.4 years.

After the Madhes, Kosi and Lumbini Provinces are the most polluted — especially in towns along industrial corridors and near the border. Karnali Province was by far the cleanest, followed by Sudurpaschim.

Read also: Epicentre of pollution, Sonia Awale

Air pollution is now the leading external threat to life expectancy in Nepal, exceeding both tobacco and diet-related risks, which reduced average lifespans of Nepalis by 1.9 years and 1.3 years respectively.

The Air Quality Management Action Plan for Kathmandu Valley introduced in 2017 had identified vehicular emissions, brick kilns, and construction as the most polluting. It adopted measures to strengthen air quality monitoring, develop emissions inventory, and conduct impact assessments. Other major sources of emissions in Nepal include forest fires, crop residue and garbage burning as well as transboundary pollution from India and Pakistan.

The report says India is the world’s most polluted country with the particulate concentration in 2023 at 41 μg/m3, an average resident in India could live 3.5 years longer if pollution levels were brought down to meet the WHO guideline. Residents of New Delhi on average would live 8.2 years longer if they breathed clean air.

South Asia has some of the world’s most polluted cities. On some winter days, Kathmandu records the worst air quality in the world. In 2023, PM2.5 concentrations in South Asia declined by 9.6% between 2021 and 2022 due to lockdowns during the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

‘After a dip in 2022, particulate pollution in South Asia increased by 2.8% in 2023 — though it remained 7% lower than in 2021,’ states the report. ‘In the region’s most polluted countries, particulate pollution’s impact on life expectancy is nearly twice that of childhood, and maternal malnutrition and more than five times that of unsafe water, sanitation and handwashing.’

Elsewhere, unprecedented wildfires caused particulate concentrations to rise to levels not seen since 2011 in the United States and since 1998 in Canada. China also registered a decline in air quality, an increase of 2.8% in particulate pollution in 2023 relative to 2022, the first in a decade since the start of its ‘War on Pollution’ in 2014.

Globally, the PM2.5 concentration in 2023 was 1.5% higher than in 2022, and nearly 5 times the WHO guideline. If global particulate pollution were permanently reduced to meet this guideline, an average person around the world would gain 1.9 years of life, adding 15.1 billion total life years to the global population, the report adds.

‘Particulate pollution remained the greatest external threat to human life expectancy in 2023, with its impact comparable to smoking and surpassing other major health risks,’ the report says. ‘Its toll on life expectancy is more than 4 times that of alcohol use, 5 times that of transport injuries or unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing, and more than 6 times that of HIV/AIDS.’

The report also highlights the need for open data, and says that accessible air quality information has translated into reduced particulate concentrations and gains in life expectancy in the United States, China, and Poland.

Besides data, the report says, investment in monitoring and other air quality management infrastructure must be matched by political will, ambitious policies, capacity building, and sustained enforcement.