A survival strategy for Nepal

Two books released this week deal prominently with the Kalapani border dispute between Nepal and India, and both eschew jingoism for historical records and present pragmatic ways to resolve this bilateral irritant.

In National Security and the State: A Focus on Nepal, retired Brig-Gen Keshar Bahadur Bhandari of the Nepal Army uses Kalapani as bookends in his foreword and epilogue. Now more than ever before, he says, Nepal needs to devise and follow a national security doctrine if it is to survive between the world’s two most populous countries.

In Nepal-India Border Disputes: Mahakali and Susta edited by Pitamber Sharma, a slew of cartographers, geographers, historians and even a hydrologist pore into colonial era maps and treaties to explore why Kalapani-Lipulekh-Limpiyadhura became disputed in the first place.

Read together, the two books present ideas about how Nepal can navigate the treacherous geopolitics of being a country of 30 million squeezed between two Goliaths on either side with 2.6 billion peoples.

Nepal’s founding king Prithvi Narayan Shah already had a national security policy that he set forth in his Dibya Upadesh 250 years ago with the ‘Yam Doctrine’. The only difference is that today Nepal is a tuber betwixt three boulders, not just two.

The most direct impact of this was felt in the last three years when Nepal’s politicians went at each other with hammers and tongs, weaponising the MCC, and in the process offending all three powers: the United States, China, India.

Bhandari’s recommendation is that Nepal has no option but to follow another one of king Prithvi’s guiding security principles: ‘Jai katak nagarnu, jhikikatak garnu’ (Don’t provoke needlessly, but be ready to defend.)

Reading the historical recaps in National Security and the State, it becomes clear that the threat to Nepal’s national security since the Gurkha Conquest in 1769, and especially after 1816, was not so much from belligerent neighbours, but from within the royal court in Kathmandu itself.

The royal families and their courtiers were entangled in endless conspiracies, vengeance and violence. The constant back-stabbing periodically erupted in ‘front-stabbing’ in the Bhandarkhal and Kot massacres, and even the murder of the royals in 2001.

The Shah and Rana dynasties were historically prone to feuds over succession, and some of this was because of the promiscuity of monarchs who begat progeny from multiple queens and concubines. Courtiers and advisers took sides, and rival regent queens appealed for support from the East India Company via the British Resident.

In that respect, contemporary politics in the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal is not much different, as politically promiscuous leaders openly seek patronage of powerful actors in Delhi or Beijing in their in-house power struggles.

Read also: The India-Nepal-China geopolitical tri-junction, Kunda Dixit

Bhandari compares the security doctrine of other small states like Israel which punch above their weight, but says also-landlocked Mongolia could be a more appropriate model for Nepal: ‘What China is to Mongolia, India is to Nepal … what Russia is to Mongolia, China is to Nepal.’

Unlike Nepal, which is vulnerable due to its overwhelming economic dependence on India, Mongolia has created a ‘third neighbour’ to boost its economic security, the author argues.

Nepal is not a ‘small’ country, it is just small compared to its giant neighbours. When it became the oldest nation state in South Asia two-and-half centuries ago, there were only 22 other countries in the world, and today it is the 40th most populous in the world.

Bhandari dissects the term ‘nation-state’, and puts forth the argument that because of its ethnic diversity Nepal is actually a ‘state-nation’. As someone who was also involved in peacekeeping operations in Afghanistan, the author wants steps to be taken to prevent potential ethno-cultural conflict in Nepal.

Although there are chapters on the Nepal Army, and especially its conduct during the Maoist insurgency, the book expands the definition of national security beyond the military to also refer to political stability, economic security, cyber security, human security and even climate security.

The reader could wonder why Nepal even needs a national army when it may not be much of a deterrence against foreign invasion. Like Costa Rica, it could free up a chunk of its budget to resolve precursors to internal conflict like social injustice, inequity and poor governance.

National Security and the State is a largely objective assessment of Nepal’s security concerns, but on some issues Brig-Gen Bhandari does take a stance. He postulates that Nepal might still be a monarchy if the Comprehensive Peace Accord of 2006 was between the Maoists and the Royal Nepal Army, instead of with the 7-party Alliance.

He also has strong views on regulating the 1,880km India-Nepal open border because ‘it has done more bad and good to Nepal … exacerbating security problems’. He also maintains that secularism was covertly added into the 2015 Constitution, and that: ‘The cause of Hindu religion would protect many of Nepal’s national security interests.’

Going by the intolerance and polarity in India today, Nepal may have to think twice about importing insecurity from the South. The ‘soft power’ of religion may not do much to firm up Nepal’s ‘soft state’.

The border dispute with India is one of Nepal’s major security concerns, and Nepal-India Border Disputes: Mahakali and Susta tries to put the matter to rest with chapters by Nepali experts including geographer Mangal Siddhi Manandhar, former government secretary Dwarika Nath Dhungel, geodetic engineer Prabhakar Sharma, and historian Tri Ratna Manandhar.

As geography professor and former head of the National Planning Commission Pitamber Sharma concludes in his overview, ‘The boundary issues between Nepal and India can be settled only by the strict obedience of the Sugauli Treaty.’

Read also: Territorialism, Editorial

That treaty between the British East India Company and the Gorkha Empire signed in 1816 shrank Nepal to territory west of the Mechi and east of the Mahakali rivers. But the treaty did not have a map, and it was left to interpretation which was the main flow of the Mahakali at its upper reaches in the tri-junction between Nepal, India and China.

This compilation makes a case for Nepal’s claim, but does so without falling into the nationalistic trap, presenting an objective analysis of why and where the boundary was changed. The conclusion: disputes over the river borders at Kalapani and Susta are a legacy of British India.

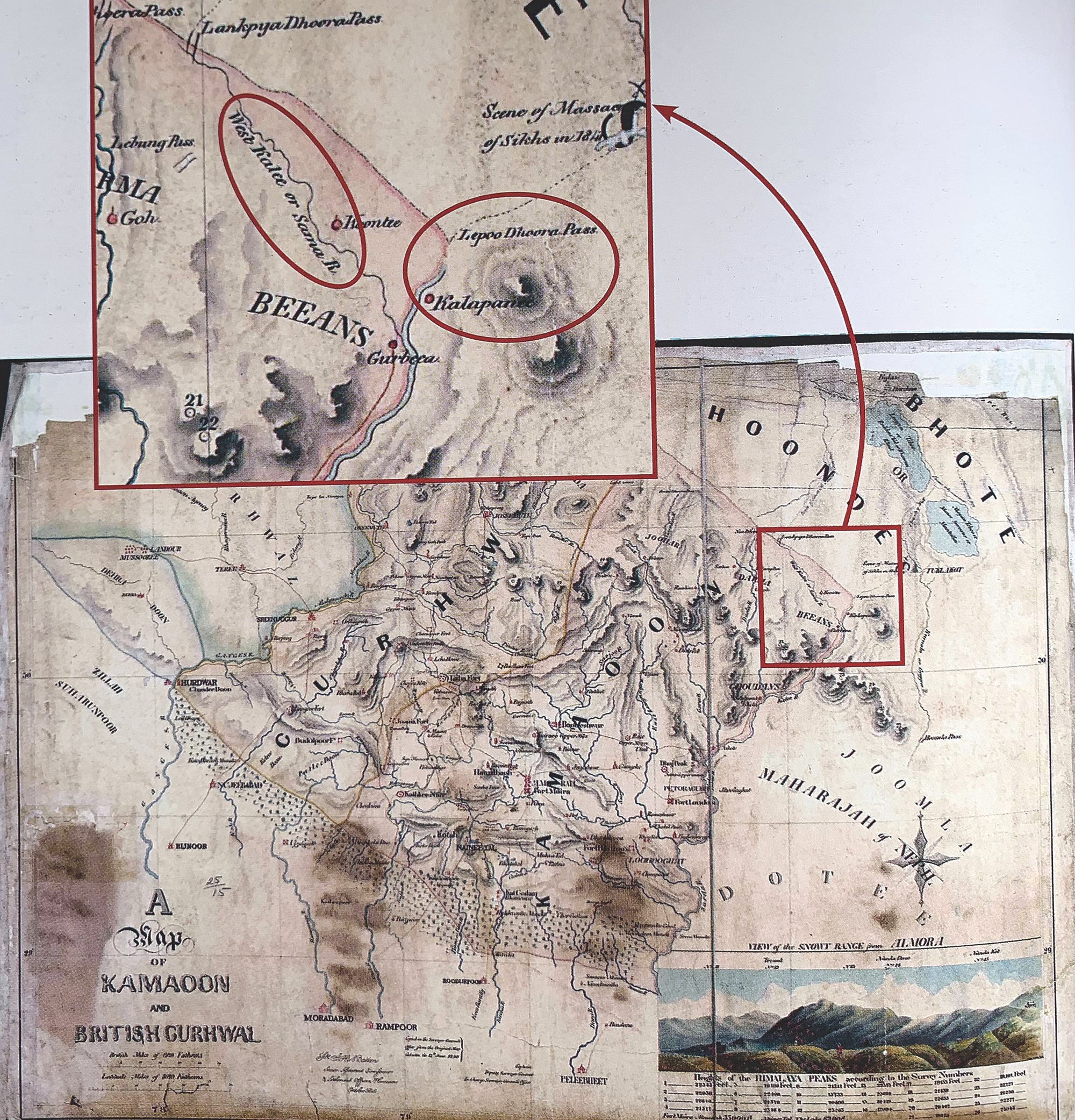

As Dwarika Dhungel points out in his chapter, early maps showed the Kali River originating in Limpiyadhura but the British later found that there was a much easier trade route to Tibet for the import of valuable shatoosh baby antelope wool along a tributary to Lipu Pass.

They then surreptitiously manipulated their survey maps to first cover up the Kali (Kuti Yangdi) and then show Lipu Khola as the main river, shifting the border eastwards. Dhungel notes: ‘How a lesser stream could be recognised as the main branch of the Kali is beyond any logic.’

If trade was the main preoccupation for Britain, for independent India it was the strategic importance of Lipu Pass — especially after the border war with China in 1962. King Mahendra allowed the Indian Army to ‘temporarily’ stay in Kalapani, and it appears to have been historical Nepali indifference by local authorities as well as faraway Kathmandu that allowed the Indians to stay put.

With Susta, the reason for the dispute is the shifting main channel of the Gandak westwards, and came to the fore in the 1960s. Nearly 40sq km of what was once Nepali territory now lies in India if one is to accept the joint Nepal-Britain Rozar Martin maps of 1817.

It is clear that colonial Britain pushed the Kalapani boundary for its trade interest and left India to deal with the consequences with Nepal, which it is doing to this day. The border issue is then used by politicians in both Kathmandu and New Delhi to wave the populist flag from time to time. China’s past border agreements with India on Lipulekh have shown that Nepal cannot rely on Beijing for support.

In the epilogue to National Security and the State, Brig-Gen Bhandari urges Nepali leaders to use ‘proper lobbying and persuasive pressure’ to either make Kalapani a peace buffer, or to swap it, as example, for a permanent highway corridor from the southeast tip of Nepal to Bangladesh through Indian territory.

His advice: ‘Since a small state cannot change its neighbours, it has to learn to live with them … more so Nepal can bring the two neighbours with diverse political and sociocultural values closer for a common and great economic interest.’

Read also: Nepal needs intelligent intelligence, Dipak Gurung

National Security and the State: A Focus on Nepal

By Keshar Bahadur Bhandari

Nepa-laya, 2022

426 pages, Rs 995

Also available through Thuprai and Amazon

Nepal-India Border Disputes: Mahakali and Susta

Edited With an Introduction by Pitamber Sharma

Mandala Book Point, 2022

192 pages, Rs 1,595

Read also: Stories of Nepal’s summiteers, Ashish Dhakal

writer

Kunda Dixit is the former editor and publisher of Nepali Times. He is the author of 'Dateline Earth: Journalism As If the Planet Mattered' and 'A People War' trilogy of the Nepal conflict. He has a Masters in Journalism from Columbia University and is Visiting Faculty at New York University (Abu Dhabi Campus).