Good housekeeping

Receptionists, guest-relations officers, the concierge, restaurant staff are the visible aspects of fancy hotels. But behind the luxurious façade is the housekeeping department, and not much of its nitty-gritty work is apparent to guests.

There are high expectations when it comes to hygiene standards and trust in a luxury hotel, but the people who make this possible work hard behind the scenes and are not readily noticeable.

At the end of the day, housekeeping is about cleaning, cleaning and cleaning. But there is so much more that goes behind it. Guests, especially in five-star hotels always have high expectations about sanitation and hygiene standards, and even more so after Covid.

I am currently an Executive Housekeeper at the InterContinental in Muscat, Oman. My career in housekeeping and laundry operations spans 20 years in multiple luxury hotels in Nepal, India and Oman. And like with everything else, my career can be divided into two parts: pre- and post-Covid.

In the 17 years before the pandemic it felt like the housekeeping department was mostly undervalued. But the three years after Covid, hygiene and cleanliness have become paramount in the hospitality sector, and especially with the housekeeping department.

I used to have moments of doubt about why I chose to remain in this unappreciated department. “It’s just housekeeping,” I used to think, hoping to get a more glamorous job at the front desk. But after Covid, housekeeping has been recognised more prominently for its critical role in hotel operations.

The pandemic was a scary time. First of all, guest numbers fell. And it became risky because our hotels were used by Covid-19 patients or those who had to quarantine. There was heightened anxiety among staff to clean rooms or do laundry due to fear of exposure, especially in the beginning when it was not clear just how lethal the virus was. None of us wanted to die on the job, of course.

As the head of my department, I had to lead by example and work alongside my staff, motivate them and look for the safest ways to get our work done. Protocols by the hotel and the Oman government were strictly adhered to. We dressed like astronauts, and sanitised the hotel, dropped off essentials like food to rooms, packed off infected laundry, and we were constantly paranoid about being infected.

But Covid-19 also shed light on the role of our otherwise invisible department, and our work in this sector across the world gained prominence and appreciation.

I felt this work was recognised when I was recently awarded the Best Hotel Housekeeper (Regional) in the Middle East Cleaning and Hygiene Awards in Dubai. I had not expected it, but felt proud to receive my regional award in my daura, suruwal and topi, representing Nepal and my employer at the ceremony.

Even while we devised internal housekeeping strategies in our hotel during the pandemic, I was also equally worried about other Nepalis in Oman and the situation back home in Nepal. As a member of The Non-resident Nepalese Social Club of Oman, we tried to come up with ideas about how we could help our motherland.

In 2021, with the Delta variant sweeping Nepal, it was evident that lack of oxygen was going to be a crisis back home. We had initially planned to send funds to China so that the Non-Resident Nepalese Association (NRNA) chapter there could buy oxygen cylinders and ship them to Kathmandu, but we found out that it could be done from Oman itself with support from the Nepal Embassy and the NRN Social Club.

The budget was going to be Rs10 million, and the central NRNA head told us that we should go ahead with the purchase and in case we ran out of money they would make up for the shortfall. The outpouring of support and love from Nepalis across the Gulf region for our crowd-funding campaign was heart-warming.

In Oman, there were many Nepalis who had low paying jobs who wanted to contribute, but did not know the bank transfer process. I remember going personally to their camps, or in case of domestic workers to the homes of employers to pick up the money.

Some Nepalis were earning just Rs15,000 or so a month in risky jobs, yet they contributed whatever they could. The spirit of solidarity was immensely encouraging.

I have come a long way since I joined Soaltee Crowne Plaza in Kathmandu in 2003, and moved to India. And there, when I applied for an internal vacancy, I did not even know where Oman was. When I got to Salalah, I was surprised by the greenery – it was different from what I had heard about the Gulf.

I did not really have to leave Soaltee for India, and I did not even have to leave India for Oman. But I wanted to try out new things, see new places and meet new challenges.

That involved a bit of risk, as it is easy to get used to the comfort of a secure job that offers familiarity. But I realised that switching jobs also gives you more bargaining power for better benefit packages, and helps with career growth and learning.

Here in Oman, most colleagues in my position or above are Europeans or locals. Initially, I felt lucky to be in meetings with them, but I was also acutely aware of my language limitations. It is by overcoming such challenges that I have been able to grow and get ahead in my career.

I am aware that my work and experience is different from other Nepali migrant workers in the region. Around 60% of the employees in my hotel are locals who work in various departments. This is not what I hear from colleagues elsewhere in the Gulf, where there are very few residents working, and most are expatriates.

This trend is expected to grow with the Oman government’s policy to prioritise local hires. Many expat jobs in West Asia are at risk because of localisation priorities of governments, and Oman in particular.

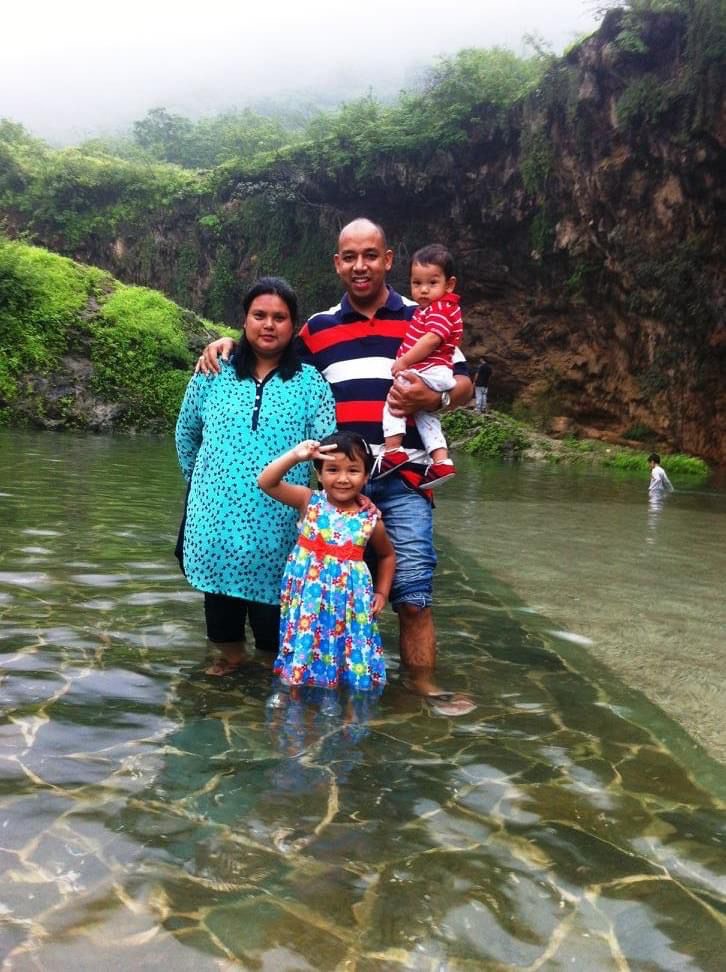

This uncertainty is one of the reasons I sent my family back to Nepal, so that the children’s education is not affected in case something happened. It was nice to have my family around, though. My son was born in Oman.

It is good to see that Nepalis are increasingly taking up more supervisory roles in the Gulf. There is more skilled migration in the medical field, engineering and management of the retail sector. However, it is very difficult for companies which want to directly hire Nepalis to do so because of the Nepal government’s restrictive and bureaucratic policies.

Employers like mine therefore are reluctant to hire directly for non-bulk hire positions like chefs from Nepal because it is not worth the effort and headache when the same position can be filled much easily by Indians and Filipinos. The Nepali authorities must seriously reconsider this.

But my most important advice to Nepalis who want to go for foreign employment is to refrain from applying for a while, but to do proper research on the available opportunity. The type of company determines the migration experience. Fraudulent recruiters who make false promises, and lack of research by migrants who are in a rush to just leave Nepal can put them in difficult positions.

What makes it worse is inadequate pre-departure orientation which means many workers are simply unprepared and uninformed when they arrive in Oman.

I am not sure when I will return to Nepal for good. It crosses my mind often but there is always one reason or another to postpone homecoming. It is in particular, the fear of whether I will be able to work and do well in the country after being away for so long. Nothing happens in Nepal without access and networking ability.

We also are not very familiar with market contexts in Nepal, which makes the possibility of making wrong investment decisions of our hard-earned savings. I am talking to fellow diaspora friends about eventually starting a resort in Nepal because this is what I have expertise in.

How and when that happens is a different question. Till then I will be a frequent short-term visitor to my own country to see family and friends before returning to the job of head of housekeeping.

Translated from a conversation in Nepali.

Diaspora Diaries is a regular column in Nepali Times providing a platform for Nepalis to share their experiences of living, working, studying abroad. Authentic and original entries can be sent to [email protected] with ‘Diaspora Diaries in the subject line.