Justice for Sale

A n June 2014, police arrested hotel owner Lekhnath Bhandari in Butwal for raping a 14-year-old girl who was his housemaid.

During police interrogation, Bhandari admitted to having raped the girl repeatedly. She was pregnant with a seven-month baby when he was caught.

But Bhandari never went to jail, he got a Dalit man to marry the girl who is now raising a four-year-old baby.

During the trial, Bhandari’s lawyers claimed police coerced him to confess to the rape and that his sexual relationship was consensual. Public prosecutors argued it was still rape because she was a minor, and produced a birth certificate which showed the girl was born on 10 January 1999 and was just 14 years old when Bhandari forcibly had sex with her. But defence lawyers presented a fake birth certificate, claiming she was born on 1 November 1995, and so had already turned 19 at the time of the crime.

The new document was issued by a local VDC three days after Bhandari’s arrest, but the court still gave more credence to that dodgy document rather than the girl’s original birth certificate. The judge ruled she was not raped but had consensual sex with her employer. The Appellate Court upheld the District Court’s verdict, but the Supreme Court, acting on a writ petition, recently agreed to re-examine the case. The girl is still waiting for justice.

Bhandari used his money and his proximity to political power to get himself off the hook, making this an iconic case, emblematic of the state of impunity in Nepal today.

Activists say cases like these embolden men to assault, rape and even murder women and girls without ever answering for their crimes, leading to the current epidemic of rape in Nepal.

Read also: "Republic of Rape"

Writer and activist Sabitri Gautam says: “Only a few rapists are taken to court, and even if they do, they are released on bail. This erodes the faith of survivors on the justice system, and sends the message to men that they can get away with rape.”

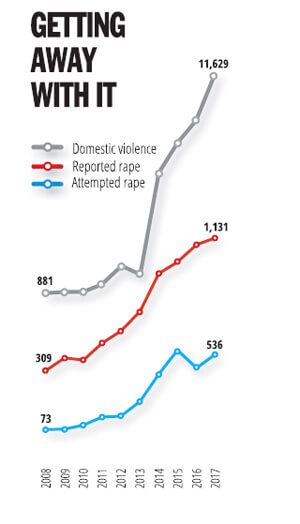

The number of rape cases recorded by police nationwide has increased four times in the last decade -- totaling 1,131 rape cases last year, which is almost three rapes a day.

In 2013, a UN report estimated that 74% Nepali women have been raped, sexually assaulted or abused. A recent report by Red Cross Nepal shows rapes are on the rise, especially in areas affected by the 2015 earthquake, where hundreds of thousands of families still live in flimsy shelters.

But most victims prefer to remain silent, which shows their lack of faith in the justice system. Only the most extreme cases grab headlines and spark protests on the streets like the ones that followed the murder of a 13-year-old girl last month in Kanchanpur district in far-western Nepal. A post-mortem showed she was raped before being choked to death in a sugarcane field. Police caught a mentally unstable person this week, but family members say they have been pressured by police to accept him as the perpetrator, and that the police are not going after the real criminal.

Read Also: The roots of rape, Kedar Sharma

A photo of the girl’s body published in some mainstream dailies outraged the nation, and as the anger against impunity grew some women activists demonstrated in Kathmandu this weekend, slamming the government for not doing enough to go after rapists, and demanding the death penalty for the crime.

After the Kanchanpur rape-murder, MPs across party lines tabled a resolution in Parliament to take urgent and stringent measures to prevent rape. But Speaker Krishna Bahadur Mahara put the resolution on hold for weeks, reportedly at the behest of Prime Minister K P Oli.

Read also: Rape as a weapon of War, Tufan Neupane

Nepali Congress MP Pushpa Bhusal says: “Parliament was not even allowed to debate the resolution, which shows the government is not really serious about controlling the widespread cases of rape.”

The controversial Criminal Code which came into effect on 17 August also has provisions that could actually encourage rapists. A person found guilty of raping his wife can be imprisoned up to five years under the new law. Previously, it was a minimum of three years of imprisonment.

Explains Advocate Sushma Gautam: “Up to five years could also mean just a day in prison.”

Under the previous Muluki Ain, the statute of limitation was 35 days, and that has been extended to a year. But activists say even one year is too short for minors and children who may be intimidated by perpetrators.

“Some girls are repeatedly raped since their childhood, and they need time to overcome the trauma and fight for justice,” says Gautam, “for them, one year is not enough time.”

Read also: Rape for ransom, Shatrudhan Kumar Shah

Behind closed doors, Namrata Sharma and Aruna Uprety

Land for rape

Devi Prasad Subedi of Bardia is a notorious criminal. In 2008, he was caught by neighbours after raping a 13-year-old girl. He admitted to the crime, but never went to jail.

A local mediating committee allowed Subedi, then 45, to go free after he agreed in writing (above) to give a portion of his property to the victim’s father. No one asked the girl whether she was happy to settle the case for a small plot of land.

Three years later, 22-year-old Sitaram Tharu raped a 16-year-old girl in the same village. But, like Subedi, he did not go to jail either. Because of the precedent, locals settled the case after the rapist’s family agreed to transfer a parcel of land worth Rs50,000 to the victim’s family.

(Names are obscured to protect the identity of the victim.)

Binda Pandey, MP (NCP)

MPs across party lines have come together to register a resolution in Parliament to instruct the government about actions to be taken to address the question of rape. It contains four provisions: for all people’s representatives to raise their voices against rape and other forms of sexual violence, punishment to the perpetrator and justice, treatment, rehabilitation and compensation for the victim. Debate on the proposal has been delayed because of other matters, the ball is now in the Speaker’s court.

Sabitri Gautam, Writer

Society describes a rape victim as having ‘lost her honour’. Actually it should be the rapist who should feels dishonoured. The victim has the right to return to normal life without fear, intimidation or stigmatisation. Rapists may be taken to the courts, but they are released on bail. Perpetrators walk free, while victims have to relive their trauma over and over again in the court. Many victims find it too overwhelming and let it be, encouraging impunity. The Home Minister needs to answer these questions in Parliament.

Sushma Gautam, Advocate

One issue of vital importance in rape cases is the statute of limitation. Rape cases had to be registered within 35 days of the crime; this was impractical and it deprived women of justice. After a long struggle, it was increased to six months, and the latest Criminal Code has increased it to one year. Incest victims, especially, should be able to lodge a complaint even after attaining adulthood. Other loopholes in the Code need revision, including what constitutes marital rape.

Ganga Pathak, Psychologist

Sex education must start at home, parents and teachers need to be involved, Many patients come to me for counseling for depression, anxiety, abnormal behaviour or having bad grades, but the real the reason could be sexual abuse. The child may have been abused by her uncle or brother, but does not open up because of disgrace to the family. It is better to focus on not allowing rape to happen rather than addressing the punishment after the crime has been committed.

Ayushma Regmi, Teacher

It is clear from many crimes that rapes are usually committed by a known person, someone the victim trusts, perhaps even friends or relatives. But as a teacher, how am I to tell my students not to trust their guardians or relatives? Sex education should also include information on rape, good touch/bad touch, and about being able to say ‘no’. I am worried about talk of ‘protecting women’. Instead of empowering, such an approach may be portraying women as being even weaker.