No time like the past

The past often feels like a foreign country, as British author LP Hartley once famously wrote, because ‘they do things differently there’.

There is a ring of truth in these words as one takes a walk around the Hanuman Dhoka Palace complex in Kathmandu. The temples and the statues, their grandiosity now laced with brown dust, age-worn and almost dwarfed by the rising jungle of cement and iron.

But 400 years ago, all this must have felt like an entirely different world.

While most of the buildings still stand, having survived earthquakes and successive renovations and remodelling, many of the statues have been stolen and are in exile in museums and private collections overseas.

The former palace complex has not changed much since the Malla era, but the surroundings have. The valley is so longer the emerald jewel it once was where Tantric gurus transformed into eagles and appeased the gods, when the air mixed the sweet aroma of flowers rustling in the breeze. The king in one of the three city states could walk to the balcony of his palace and check if there was any new construction taking place in a neighbouring kingdom.

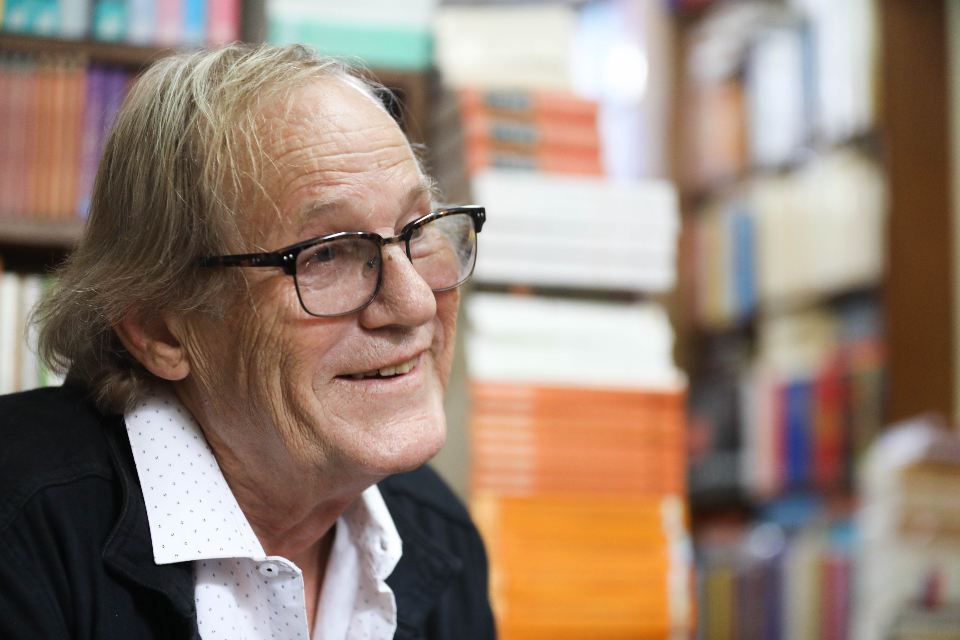

There seems at once a great chasm between the past and the present, made wider by the dramatically divergent look of the Nepal Mandala today –– one that noted historian and scholar of Himalayan and Nepali art Éric Chazot tries to commute in his novel Le Seigneur de Katmandou.

Read : An archive of one’s own, Pratibha Tuladhar

Published by Éditions el Viso in 2021, this French-language historical fiction is a detailed retelling – and, at times, perhaps even reimagining – of the life and times of Pratap Malla, told in his own voice, almost as though it were from his diary.

The narrative weaves together the legends and inscriptions of the Valley in the latter half of the 17th-century to create a portrait of Pratap Malla not just as a king, but also as a poet, a philosopher, a son, a father, and a husband.

It is already a daunting task to write a historical novel –– to try and capture a period, its persons and sensibilities often so far removed. As history is rooted in records, it leaves an author little room to indiscriminately invent.

Now add into the mix the figure of Pratap Malla, arguably one of the best-known kings of Kathmandu. His historical persona has been embellished and undermined in the last three centuries, owing to folklore, propaganda and scant contemporary records.

Historian Lila Bhakta Munankarmi in his book मल्लकालीन नेपाल describes Pratap Malla as being ‘glorious and brave’ and ‘an intellectual and a poet’, who ‘established numerous temples, shrines and chaitya in Kathmandu, many of whom are still standing.’

He was a king who built the Rani Pokhari for his queen who was grieving the death of their son, and allegedly kept a harem of 3,000 young girls, even ravishing one 11-year-old and causing her death.

This already ambivalent portraiture is coloured further by the Pratap Malla’s cultural and religious legacies, many of which are still standing in Kathmandu: the statue of Hanuman outside the Hanuman Dhoka Palace, Chyasin Dega, the Bhandarkhal pond, Anantapur and Pratappur spires in the Swayambhu complex, Guheshwari temple, Bhimsensthan, and the many chok inside his palace.

Read also: Losing loose change in Nepal, Ashish Dhakal

Chazot’s novel is in some ways a representation of this multiplicity of character. It is reminiscent of the cubist paintings – for instance Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) – and makes no attempt to justify actions or pass judgment –– as Chazot himself admits, that is not what he is trying to do with Le Seigneur de Katmandou.

It was in fact to understand him, to explore his philosophy and his character. Chazot is a scholar of masks and art of the Himalaya, with a special interest in Tantrism. In 2015, his translation of the Tantra of Chandamaharosana into French at the behest of a Newa guru Dharma Guruji was published, and in 2016 he came out with another book on the Tantric art of Nepal, Tantra: Théologie de l'amour et de la liberté, which goes into the details of its philosophy and aesthetics.

Pratap Malla was already a fascinating subject for Chazot who first arrived in Nepal in 1973. A contemporary of Shah Jahan in Mughal India and Louis XIV in Bourbon France, he too showed fierce love for the arts and philosophy, sometimes with a dash of decadence. Chazot finished the first draft of what would be Le Seigneur de Katmandou in 1979, but it was 600 pages long, he recalls, “and very complicated”.

So, he began to rewrite. “I wasn’t writing every day,” he says. “Sometimes I would write a few pages, take a break for a couple years, and then return to it.” The published version is the fourth draft of the work.

He had previously planned a series of novels focusing on one figure from each dynasty of rulers of Nepal, the Malla, the Shah and the Rana, but decided to abandon that for the time being to focus on the story of Pratap Malla.

“I really wanted to write a good novel,” he says. “It could not be a little book you read once, enjoy and then forget about it. It had to be concrete and well-written with historical facts integrated with the legends of Pratap Malla so that people find it believable.”

Chazot could not remove the legends, such as Pratap Malla entering the mythical caverns of Shantipur temple in Swayambhu during a drought to recover a paubha drawn in the Naga’s blood to bring back rain. Or the story of how Jamana Gubhaju once turned himself into an eagle and carried away the heart of a young boy one foreign sorcerer had cut up and promised to bring back to life through Tantra.

“I could not say that because I am a historian, none of that could have happened,” he adds. Instead, Chazot built the book as a first-person narration by Pratap Malla, giving us a direct look into the mind and impressions of the king.

Sometimes the king himself appears to be an unreliable narrator, which then prompts us to try and sift, and wonder if separating facts and fiction truly matters after all, because would Pratap Malla be the character he is without the legends and stories?

A devout and ambitious king, it had been his great wish to unite the three kingdoms of Nepal Mandala fractured by King Jayayakshya Malla some 200 years before, for which he was constantly at war with Yala (Patan) and Khwopa (Bhaktapur).

But it was also during this time that Yen (Kantipur, or Kathmandu) saw unprecedented economic growth, fuelled largely by a treaty with Tibet which allowed the Newa merchants of the city a virtual monopoly over trade with India and Tibet.

Read Also:

The history of heritage, Ashish Dhakal

Losing loose change in Nepal, Ashish Dhakal

Tibet was also to make a token payment in gold and silver annually to Kathmandu, and Nepal would mint coins for Tibet, allowing the King to profit vastly from these transactions and invest in the arts and culture.

“He was an important king of Nepal and there are many inscriptions in his name,” says Chazot. “He was also a tantric king and pretended to know 15 languages. I was always fascinated by him.”

The famous stone inscription outside the Hanuman Dhoka Palace to the goddess Kalika is written in 15 languages, including Farsi, Maithili, Hindi, Tibetan, Nepal Bhasa, Arabic, with a surprise appearance by three European words for the seasons: AVTOMNE, WINTER and LHIVERT –– the last one a lasting spelling error, maybe made by a distracted sculptor or scribe.

Perhaps the Jesuit fathers Albert d'Orville and Johann Grüber taught the king the words, but the inscription remains undeciphered. In a funny scene with this clever linguistic invention, Chazot describes Pratap Malla remarking: ‘je m’amusais profondément de voir leur embarras lorsque je les interrogeais sur la signification de mon poème!’ (I found it deeply amusing to see their embarrassment when I asked them about the meaning of my poem).

Chazot explains: “He called himself Kavindra – the King of poets. For me, this was an interesting idea because he was already a king, but he placed poetry above the kingdom of worldly affairs, and he wanted to be king of that too.”

It is said that whosoever can read all 15 languages on that tablet will be blessed with milk miraculously flowing out of a duct at the bottom of the stone inscription. It may have flowed only once.

Read also: The historic Kathmandu beneath our feet, Sahina Shrestha

But Chazot takes care to not confound us with Pratap Malla’s grandeur, for that would only give half-a-portrait. One side of the coin shows the king as an accomplished philosopher with care for his subjects and royal dreams. He wants to learn everything and bring lasting prosperity to his kingdom.

On the obverse is an often impatient, lascivious man, a soul that is equally hungry for power as it is for knowledge, a man who may or may not have conspired to have a popular kaji murdered who also happened to be a brother-in-law. And a man who, to repent for killing a prepubescent girl, performs tuladan – the practice of offering Brahmins gold and silver equal to one’s weight.

The reader may be tempted to suspect the validity of his claims and contrition, and the book invites one to question the act of writing itself, of telling stories. Where may we draw the line? What is honest and dishonest? The answer, readers must themselves decide.

“In building the character and trying to understand,” Chazot adds, “I also want to caution the reader because it is not an objective retelling.” The novel is not just the story of the past, it is a picture of a man who also wants to be a hero. And Pratap Malla himself narrates his story.

As the author, however, Chazot has tried to keep the story simple, subtle and coherent, often using juxtaposition to show the contrasting or coalescing viewpoints of cultures, countries and cults.

“Brick by brick I put the story together,” he says, taking trips to the Hanuman Dhoka Palace, the temples, poring over the inscription, caressing the curves and the carvings to try and get a sense of what the king himself might have felt walking through his city almost 400 years ago.

For written sources, he turned to the works by DR Regmi, Sylvain Lévi, A.W. Macdonald and Anne Vergati Stahl. He hopes Le Seigneur de Katmandou will be an addition to the œuvre that introduces Nepal, its history and culture to the world. An English translation is currently being undertaken by Vajra Publication.

“Pratap Malla wanted to be a myth,” Chazot says, “and I have tried to make that come true.”

Le Seigneur de Katmandou

Éric Chazot

Publisher: Éditions el Viso (2021)

Pages: 256

Read also: A tale of three cities, Ashish Dhakal

writer