Mind the gap

Seismologists say that the 2015 disaster in Nepal was the most data-rich Himalayan earthquake ever studied. The 7.8 magnitude earthquake moved eastwards along a rupture zone from its epicentre in Gorkha, but mysteriously lost speed and intensity by the time it arrived in Kathmandu before fizzling out south of the Valley. Nearly all the 14 districts affected are east of Gorkha. The amplitude and the pulse ripples in the sediment of the Valley floor downed many monuments, but left most of the concrete buildings intact.

The 2015 earthquakes were an important warning for us to be better prepared for the really big one. Despite the tragic loss of 8,900 lives, Nepal got off relatively lightly three years ago for a quake of that magnitude. Lots of other factors kept the fatalities low: had it struck on a weekday many tens of thousands of school children would have been killed in the 8,000 schools that were badly damaged. Telecommunications did not go down, Kathmandu airport was back in operation within hours, and the highways remained passable.

Read Also: Past disasters foretold, Om Astha Rai

Next time we may not be so lucky. As coverage in this special third anniversary edition of this newspaper points out many of the badly-engineered ferrocement structures in Kathmandu will come down in the next big one. We will need specialised equipment and personnel trained in search, locate, rescue in collapsed concrete structures.

Newly-elected municipalities will have to ensure preparedness by stopping encroachment on urban open spaces, prepositioning water and digging equipment, and have contingencies for telecommunications and transportation networks being knocked out.

Read Also: 1/3 empty or 2/3 full, Nigel Fisher

This is not scaremongering. Seismologists predict two dangers we have to prepare ourselves for: one is the incomplete tension release after 2015 along faultlines below Kathmandu Valley. This could set off another quake below 8 magnitude in the next decades.

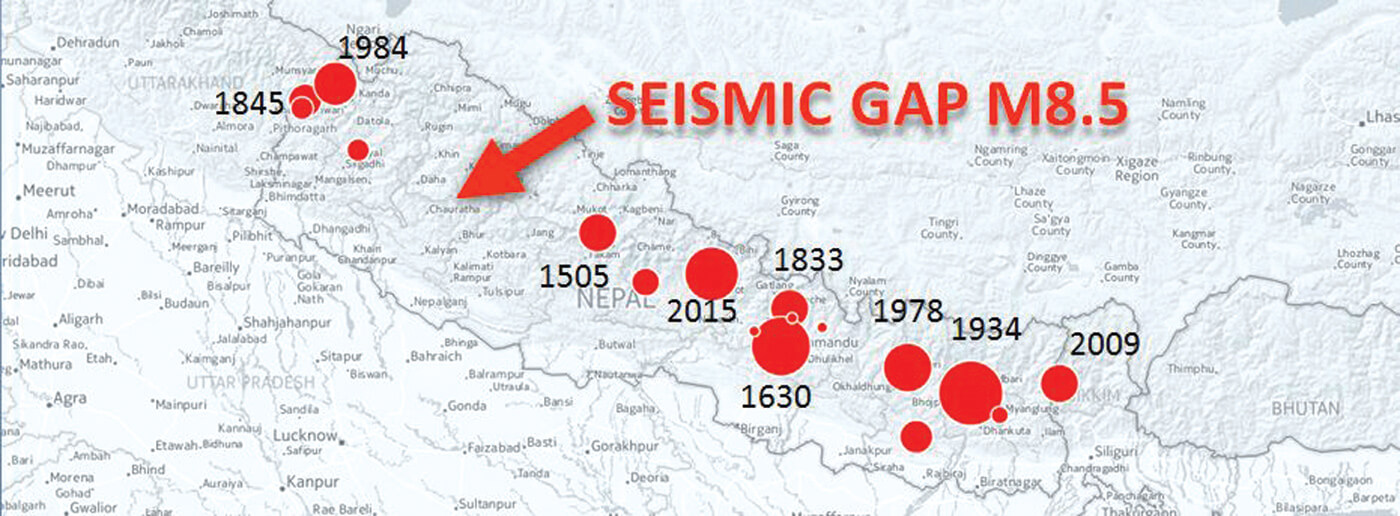

More worrying is the seismic gap in western Nepal where there hasn’t been a mega-earthquake in the last 700 years (see map). Monastic records in Tibet allow us to pinpoint the exact time of the last big earthquake there: 6AM on 1 June 1505. Estimated at 8.9, that earthquake devastated north India, destroyed Agra and other Moghul cities, may have trigged the Annapurna slope collapse that dammed the Seti River unleashing a tsunami when it burst. Pokhara today sits on the debris field of that cataclysmic flood.

Read Also: How prepared are we for the next big one, Sashi Shrestha

Himalayan seismologist Roger Bilham of Colorado University says there is now enough slip deficit beneath western Nepal that can trigger a sudden elastic rebound, moving the terrain southwards and upwards by a shocking 14m in seconds.

An earthquake of 8.5 magnitude epicentred in Surkhet, for instance, would not just destroy much of western Nepal, but also the densely packed cities of the Indo-Gangetic plains. This could conceivably be the greatest loss of life in a natural disaster in human history. The shaking would be intense enough to devastate Kathmandu as well.

As our coverage in this issue points out, it is now time to think beyond reconstruction in the 14 districts affected in 2015 to upgrading preparedness and disaster response in central and western Nepal. Buildings, especially schools and hospitals, need to be urgently retrofitted.

The Gorkha Earthquake three years ago was just a forewarning of an even bigger disaster to come.

Read also:

Stirred, not shaken, Kunda Dixit

Preparing to be prepared, Kunda Dixit

Not out of danger yet, Sonia Awale

A concrete future, Sonia Awale