A Plastic republic

An integral part of modern lifestyle and the global market, plastic is an essential component in the latest gadgets and luxury goods, and in packaging everything from electric appliances to food items. Around the world, governments are under growing public pressure to ban single use plastic, to use less and recycle everything. Rwanda, and even parts of Somalia have banned plastic. There is no reason why Nepal cannot do the same, but repeated government efforts to ban plastic bags have failed. Hetauda restricted the use of plastic bags some 20 years ago, but was unsuccessful.

More than 1 million plastic bags are used once and thrown away in Kathmandu Valley every day, and it now forms more than 11% of the waste. Of the 204 tons of plastic waste generated in Nepal every day, 131 tons end up in garbage piles and dumping sites.

Plastic is contaminating our water sources and the soil, it ends up in cattle feed, and is a major threat to fisheries. The floods in Bhaktapur last week were partly blamed on plastic garbage blocking drains .

When Denmark started charging for plastic bags, it reduced use by 66%. Similarly, Ireland taxed 0.15 euros per bag and brought down use by a whopping 94%. London has also been able to control plastic use since it started charging 5 pence per bag.

Nepal can learn from these examples, which suggest that taxing is more effective than a blanket ban.

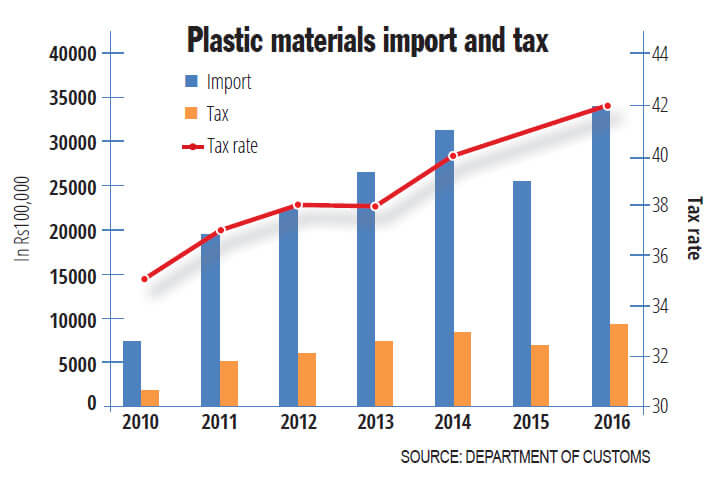

Nepal lags far behind, both in policy and implementation, despite importing plastic materials worth Rs 22billion annually and earning Rs 6billion in excise tax. Because of the source of revenue, and the lobbying by industries, a blanket ban is not realistic.

Plastic Bags Regulation and Control Directive restricts production, sale and use of plastic bags below 30 microns. Our studies have revealed that while municipalities like Byas, Hetauda, Ilam, Damak, Palpa and Pokhara have banned the use of plastic bags thinner than 30 microns and black polythene, the use is increasing in Ghorahi, Dharan and Mechinagar.

On average, a family uses 10 plastic bags per week. This means if a person is charged Rs200 for plastic bags below 30 microns, its use can be reduced to zero. When Ilam municipality implemented a penalty of Rs223, it could reduce the use of plastic bags to almost zero. Whereas in areas with full restriction, the use never went down to zero, even when businessmen and consumers were in support of the ban.

On average, plastic materials are charged 34% tax, which isn’t high compared to other items. Timely monitoring is equally important. We observed 282 travellers in 24 municipalities during our survey. Most of them didn’t carry a spare bag from home, but 9% carried plastic bags, 11% of people in areas with partial restriction were found to be carrying plastic bags while only 1% did in municipalities with full restrictions.

In addition to monitoring, we have to communicate through mass media that officers are out to catch offenders and make them pay, as well as broadcast recent arrests and penalties. We can mobilise communities and demonstrate street plays to increase the effectiveness of the campaign.

If we are to successfully implement the restriction and penalty in Kathmandu, we will save more than Rs 500 million in plastic bag waste. But more than this, we will be saving the future generations of Nepalis from dealing with our waste.

Bishal Bhardwaj, Rajesh umar Rai, Mani Nepal and Muktinath Subedi in Himal Khabarpatrika (8-14 July)

Also read: Recycle, reuse, reduce, Donatella Lorch

Rubbish Life, Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati