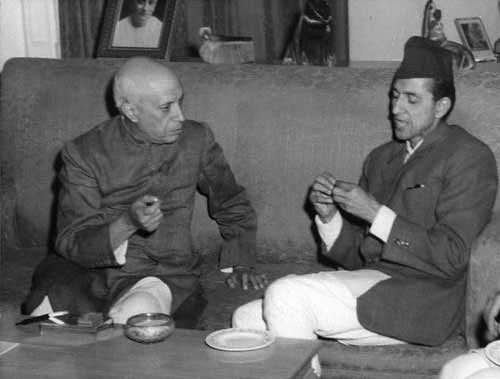

Conversation between BP Koirala and the American Consul in Calcutta in 1953

Having requested an appointment with the American Consulate in Calcutta, BP Koirala went to the Consulate on October 15, 1953, and talked with the American Consul, who sent a record of his conversation with Koirala to the American Embassy in New Delhi. The trenchant criticisms Koirala expressed about the dominant and controversial role India had assumed in the internal affairs of Nepal are well worth noting, particularly since BP was often accused of being ‘pro-Indian’ at the time.

Back then, BP’s brother, MP Koirala, was in charge of the government, but there was no Nepali Congress member in the cabinet. King Tribhuvan had left Nepal in September for medical treatment in Switzerland. BP was president of the Nepali Congress but had held no government position since November 1951. The Congress itself was split into three factions, and the Koirala brothers remained at odds.

This document (from which a few parenthetical remarks have been omitted here) is part of the U.S. State Department files on Nepal and was located in the U.S. National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

American Consul Garrett Soulen who spoke with Koirala wrote the following report at the conclusion of the meeting:

I [Consul Soulen] must say that after having read at least some of the press reports about B.P., I had expected a man older appearing in years and a person with more or less a firebrand temperament. I was surprised on both counts: B.P. appears to be not more than 35 or 36 (he says he is 40, with a 5-year-old son at school in Patna) and he was anything but a demagogue or a firebrand. I have seldom heard a less dispassionate recitation of facts and opinions from a purported nationalist. I was impressed with his [B.P.’s] apparent frankness and probable sincerity.

I could not help but think many, many times during his conversation, “I have heard this before;” the correlation between the facts and opinions as [B.P.] recited them and like facts and opinions made to me by Sikkimese in regard to their state (Bhutan also) was striking to an extreme. The gist is “big stick GOI [Government of India] policies towards border states and against minorities in those border regions, coupled with a most inept implementation of such policies.” Despite the fact that we here in Calcutta, primarily because of the reserve exercised by Indian officials in discussing these matters, undoubtedly hear much more of the other side of the question than the GOI’s, it would appear that the implementation of GOI policy toward Nepal, Sikkim, Naga Hills, Lushai Hills, and to a lesser extent Bhutan (only because they hold themselves aloof) is always to the benefit of Indians, and especially from a monetary standpoint.

Among the various subjects which B.P. brought up and on which he discoursed at some length, the following are worthy of note.

[B.P.] saw Prime Minister Nehru August 13 and on a subsequent date. At both meetings when he endeavored to point out to Nehru the errors which the Indians were committing in Nepal in the implementation of their policy, he was cut off short and told that because of geographic location Nepal was going to have to develop under the aegis of the GOI. B.P. tried to point out that Nepalis were slowly but surely developing a nationalist spirit, that this nationalist spirit could be channeled into agreeable Indo-Nepal relations which could be mutually beneficial to both countries, or it could develop as a hard core of absolute independence from all other nations, or it could develop in such a way that Communists under the guise of nationalism and with the aid, abetment and tutelage of the Communists in Tibet (possibly with the help of Indian Communists as well) could establish a Red regime on the southern slopes of the Himalayas.

When B.P. asked Nehru what Nehru’s intentions were for Nepal, Nehru reportedly was very angry with such a direct question and answered only to the effect that he, Nehru, wished to see a strong economically prosperous Nepal develop.

On the Communist issue, B.P. claims Nehru lectured him severely to the effect that for the next ten years there would be no danger from Communism to India or Nepal, because “China has her hands full with her own problems.” (In our conversation this morning the USSR was never mentioned). In B.P.’s opinion, Nehru might possibly be correct with his ten-year prognostication if he is thinking only about armed invasion of the sub-continent. However, B.P. pointed out that even with plenty of problems on their hands in China, Korea, Indo-China and Tibet, the Chinese Communists and/or their Tibetan, Nepali and Indian cohorts could still carry out enough disruptive tactics, especially in the fields of economics, industry, finance and state administration, to seriously hamstring and thwart the efforts of any but a very strong, stable national government.

[Regarding American TCA (Technical Cooperative Assistance)], B.P. said that until July 1953 he had been “quite friendly” with Paul Rose [head of the U.S. Point Four Program in Nepal] in Kathmandu and that although they had not discussed politics as such, B.P. thought Rose “understood his mind.” B.P. had occasionally visited Father Moran’s school [at Godawari] and had discussed many of his problems with that gentleman. He had over the previous year been in contact with other Americans and certain other foreigners, including British Ambassador Summerhayes, and certain FAO [the UN Food & Agriculture Organization] people who had been to Nepal on inspection trips. During the August conversations, Nehru had brought these contacts to B.P.’s attention and in no uncertain terms had let it be known that the GOI did not approve of such activities, and that such contacts should cease, especially contacts with Americans. B.P. went no further than to say that Nehru had spoken deprecatingly about America.

B.P. claims that the usurpation by the GOI of the most prominent place in Nepal’s economic and political situation is borne out by many facts. Among many which he mentioned [were that] M.P. Koirala is under the direct jurisdiction of the GOI. The GOI has also directly controlled the King. [U.S.] Ambassador Bowles’ endeavors to break through that barrier were unsuccessful. For example, a [U.S.] expert [on administration] by the name of [Merrill R.] Goodall, who is supposed to have been assigned in Nepal for a matter of three months as an adviser, lasted only two weeks before GOI forced his recall. The [American] TCA program in Nepal has been hamstrung, primarily by GOI intransigence, if not by design, which was reflected through the Government of Nepal’s lack of cooperation in getting its projects rolling. [An FAO expert] told B.P. it appeared to him that the GON was purposely holding back cooperation with TCA on the orders of the GOI.

Nepal at the present time has 11,000 men under arms. Five thousand of these men are supposedly under training with the Indian Military Mission. The remaining 6,000 are under the Nepalese Army command. The Indian Military Mission rankles most Nepalese officers, and the same feeling against it is held by the majority of the rank and file. In B.P.’s opinion, there was absolutely no necessity for the GOI to set up this separate headquarters for its military mission. In fact, the mission itself is much too large, and its scope of operations is much broader than contemplated by any Nepali who entered into the negotiations. According to B.P., the Nepali Army needs outside assistance training in only two categories: (1) engineering troops, and (2) artillery. According to him, the Gurkhas have earned a world-wide reputation as excellent infantrymen not only in world wars but also in the continuous skirmishes and incidents in which the British (with Gurkha troops) have been engaged for many years. Nepalese officers, who during the last war had certain Indian officers under their command, now find themselves with those same officers in command of them, for training purposes but nevertheless on Nepal’s soil. Nepali army officers consider themselves superior soldiers to the Indian, and although they may not have as “smart a step or cut of uniform,” they are only too willing to stand on their reputation earned through actual battle experience. Nepali Army officers are fearful that the Indian Military Mission will break down the morale of the Nepali troops, for the Indian officers tend to be haughty with the Nepali officers and on many occasions criticize them in front of Nepali troops. Evidently B.P. took up the matter of the Indian Military Mission with Nehru in August, for he remarked that Nehru had said, “Well, we have at least made your troops smart,” (meaning good appearing for parade ground exhibitions). B.P. claims that the anti-Indian feeling (which he did not specifically mention as such) pervaded the entire Nepalese Army and the police force. He believes both units have a majority of men who are extremely nationalistic in outlook.

Trade with Tibet is considerable. [B.P.] implied that India encouraged such trade and especially for Indian manufactured articles. He said that the Chinese in Tibet were assiduously cultivating Nepalese traders there, and that although these men were of small account financially and at present of little moment politically, nevertheless practically all of them were coming back into Nepal favorably impressed and to a certain extent condoning the Chinese action in Tibet. B.P. feels that these men, with their tales, have had and will continue to have a disturbing influence on the people in the mountains. He said it was not so much a question about the correctness or propriety of what the Chinese had done and were doing in Tibet, as it was the impression made on [Nepalese traders] of how much easier it is to live under a stable government (even totalitarian) than it is to live and do business in a country with practically no government.

[Regarding the Indo-Nepal trade agreement of 1950], I cannot remember all the various details [B.P.] mentioned. The gist of it was, however, that India is now pressing for the Government of Nepal (which means private traders as well) to handle all of their imports into Nepal through GOI offices. I remember one specific example of what appears to be economic exploitation: Nepal imports considerable quantities of betelnut, primarily from Malaya. It used to be possible for a Nepali trader to deal directly with a trader in Malaya or some intermediary for this commodity. Now it has to be obtained through the GOI, and if there is a licensee in India for the import of this commodity, the Nepali trader must deal through that licensee, in effect making the Indian an extra middle man to squeeze out a bit more blood from the turnip.

When B.P. was speaking about exports, imports, Indian policy, etc., he said that in August Nehru, in pointing out to him the dangers of becoming dependent upon “great countries,” had told B.P. about [U.S.] Ambassador Allen’s representation to Nehru, because India had exported a ton of thorium to Communist China; the Battle Act was mentioned in this connection. [The U.S. Mutual Defense Assistance Control Act of 1951 banned U.S. assistance to countries doing business with the Soviet Union, and India refused to accept any American-imposed limits on its trade.] Nehru was evidently incensed over that episode and had spoken very disparagingly about the United States in that connection.

B.P. claims to have very drastically revised his opinion of Nehru over the past year and a half. He said that in mid-1951 he had been warned by Jai Prakash Narayan that he, B.P., was putting much too much trust in Nehru for the good of Nepal. Narayan had continued with a softening remark to the effect that one must not put that much trust in any foreign nation’s prime minister, for countries, like people, are still antagonistic toward each other and try to take advantage. Since mid-1951, B.P. has realized more and more that Nehru is not the master of his own destiny and feels that during the past year Nehru has taken a backward step from his previous high ideals and ideology. B.P. implied that this change may have been forced upon Nehru, and actually said that a small group in the Ministry of External Affairs has been responsible for most of this retrogression. He gave Nehru the benefit of the doubt on general policy matters, but blamed Nehru for being so busy with so many things that he could not properly control his lieutenants. B.P. said that when he spoke to Nehru about generalities, they were in near agreement, but when it came to discussion of the implementation of policy, Nehru invariably became upset to the point of anger and would not listen to reason. B.P. believes that Nehru’s subordinates force upon Nehru their own ideas when it comes to implementation [of policy]; the result is probably not what Nehru had anticipated. B.P. said there is the possibility that Nehru is the kind of man who believes he must back up his subordinates in the decisions which they take whether they are right or wrong—in any event, the developing situation is not one which could be considered conducive to good Indo-Nepal relations.

B.P. stated categorically that the situation within Nepal was deteriorating and had been for the past nine months. He claims to be most anxious over the way the Communist situation will develop this next winter and spring. As he expressed it, the Communist Party is under ban but is still operating quite openly. The people are extremely dissatisfied not only with their economic ills but with the fact that their government is not a government, that day by day it becomes more and more a puppet, subject to the whims of GOI. The Nepalese people, at least those in the Valley, are fast losing faith in what government there is, and as a result, seeing practically only one alternative—Communism—are slowly but surely tending to listen more and more to the promises and claims put out by its adherents.

B.P. asked for nothing. He did say that he had hoped on his last visit to New Delhi to see Ambassador Allen but that circumstances had been inopportune. He mentioned the fact that he had no contact with the [U.S.] Embassy. I offered no help in this regard, but merely expressed my pleasure in having had an opportunity to listen to him.

Note: The above passage has been reprinted by permission from the recent book, America Meets Nepal, 1944-1952: Problems, Personalities and Political Change, by Daniel W. Edwards.

Read also:

Forgetting to remember BP, Ted Riccardi

America, Nepal and the Royal Coup, Tom Robertson