Digital verification of traditional art

New initiative uses blockchain to archive and track Nepal’s thangka and paubha across the worldTraditional thangka and paubha painters spend months hunched in small rooms making meticulous pieces of devotional art that follow ancient canons and style.

These are not starving artists hoping to make it big, these are professionals who have trained for years under strict rules and masters. They know their level, and know that a piece will take about three months of full-time work.

They set a standard price that reflects three months’ wages in Nepal. Local and foreign buyers visit the studios regularly, to acquire the pieces to keep or sell. That is often the last the artists see of their work -- they do not know where in the world it has gone, or how many times it has changed hands and for what prices.

This can be a problem because traditional art is often unsigned, so artists go unrecognised. Collectors and galleries may also be hesitant to buy or exhibit a piece if they cannot say for sure where it came from.

This is an even bigger problem in thangka and paubha because making pristine copies of the works of masters is not seen as forgery or a violation of intellectual property, but as a test of their ability to adhere to sacred tenets.

“When senior masters paint a piece, and photos of it get out, it gets copied immediately. I have heard stories of collectors selling these copies as if they were the original,” says Thimi-based artist Sundar Shrestha, who made a switch from contemporary art to paubha.

The Kathmandu-based Himalayan Art Council is trying to resolve the issues of ownership and provenance of traditional Nepali art by building a cutting-edge system that issues a tamper-proof digital certificate to each artwork.

The system tracks each time there is a transaction involving the piece, and provides a royalty to the artist each time. In doing so, the system also creates a detailed inventory of Nepal’s traditional artforms, which will prove valuable for future scholars or repatriation efforts.

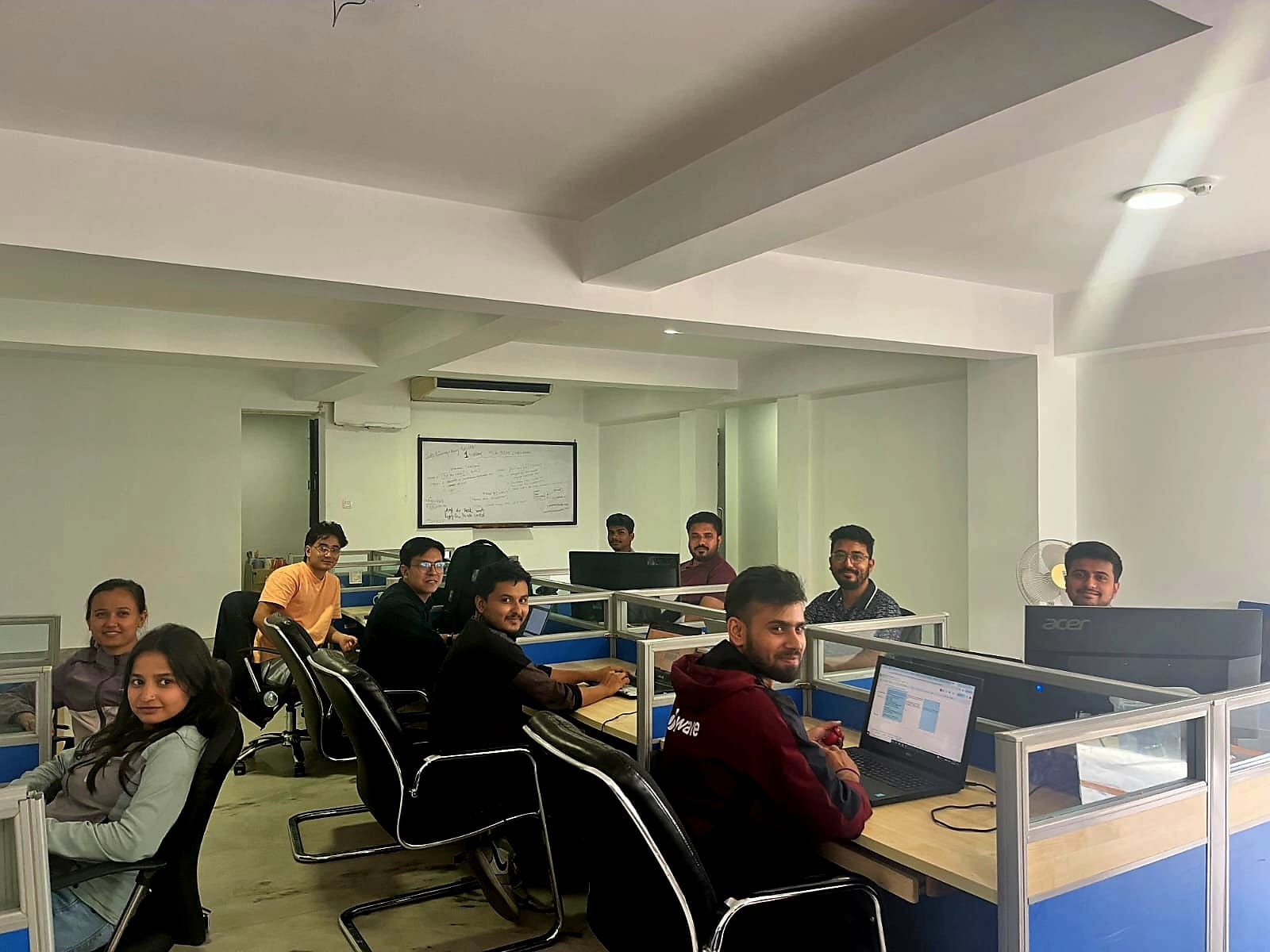

THE TEAM

Behind this initiative is a team with activist-entrepreneur Sean Howell, curator and museologist Meena Lama, Mercantile CEO Sanjib Rajbhandari, and blockchain expert Bijay Bogati.

Howell’s interest in the project started out through a connection to Nepal that began with a love for red pandas, and an invitation to promote eco-tourism. Howell has a diverse background in finance, the tech world and social communication. He has been art commissioner for Seattle, and knows all about blockchains, the technology underpinning this art initiative.

“I saw that there were many people working in art preservation in Nepal, and that current, living artists were facing problems,” explains Howell. He recognised that these problems had already been solved elsewhere in the world. “This technology is a low-cost, high-value solution that ensures artists receive fair value for their work while also establishing a digital archive of Nepali art.

"Trust is paramount for collectors," says Howell. "Thangka art has high market value globally that is not reflected in local transactions due to the opaque nature of its sales."

Building the actual system is a team of software engineers that works out of the Mercantile office in Kathmandu, led by Bijay Bogati. Bogati transitioned to blockchain in 2019 after working with Khalti as a founding engineer, and held remote senior software engineer positions for German and US-based companies.

“The most interesting part of this project is how this futuristic technology is being used in Nepal to create a digital ledger of this huge legacy of traditional artists and art,” says the soft-spoken Bogati.

Holding together the whole operation is curator Meena Lama, who has an MA in Museology and Buddhist Collections. She says, “While there is undoubtedly a commercial side to this project, the most important thing is that it helps digitally archive traditional Himalayan art and makes it much easier to study. Especially as many of the country’s finest works of art are held in private collections and risk being lost to time, damage, or disappearance.

To kickstart the project, Lama and the team selected fifty significant pieces of thangka and paubha from different artists, certified them at no cost, and exhibited them at the Patan Museum last month.

Lama’s connection to the art world and Bogati’s expertise in this new technology have also been important to get artists to buy in to the project.

“Initially, other artists and I were a little skeptical,” admits Sundar Shrestha. “But I had worked with Meena on exhibits before, and Bijay’s grasp of the tech put me to ease and made me quite excited.”

THE TECH

In the big picture, blockchain technology is part of a movement in tech referred to as ‘Web3’, which is widely regarded as the next evolution of the internet.

Instead of central authorities that control data and user-experience, such as Facebook or Google, Web3 aims to devolve power over many users, giving them more of a say over their identity, online interactions, and transactions.

One of the goals is to make digital records as reliable as physical ones, and secure enough for banking or legal transactions. Art and cultural heritage can be protected by the same trusted tools.

The Himalayan Art Council’s project follows long-established international standards by adding a secure, centralised digital layer to every record, which safeguards traditional art, gives it global credibility, and connects it to the same trusted systems used by leading institutions around the world.

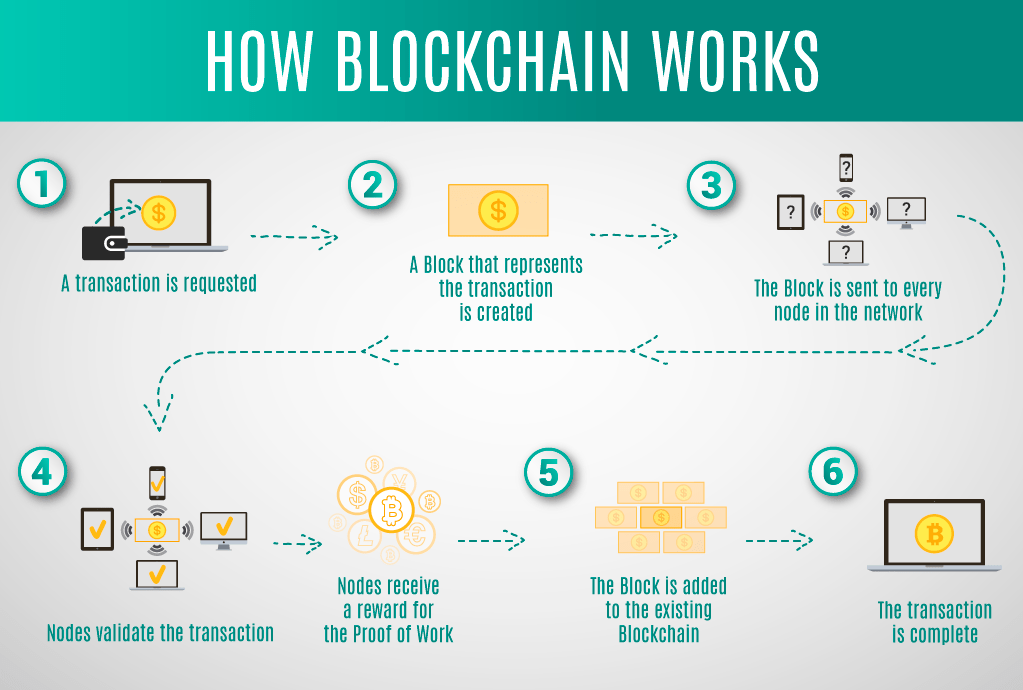

The key concept for Web3 and the Himalayan Art Council’s project is blockchain, a technology without central authority that records transactions in a way that is both secure and transparent.

Each transaction is a ‘block’, and is linked mathematically to the transaction that happened before it to create a ‘chain’ of digital records across computers, following the same security protocols used in banking.

Altering the details of any one transaction requires all the computers that are linked to agree, making tampering or fraud virtually impossible.

Himalayan Art Council would take varied data about the painting: authorship, high-resolution images, chain of ownership, transaction history and feed it into an algorithm that creates a ‘hash’, or a unique identifier for that particular piece. This hash then is turned into a QR code included on the art. Then anyone can scan the code to check the piece’s history and legitimacy.

A key feature is that every time the piece is resold, the original artist can opt to automatically receive royalties worth up to 10% of the value, and can choose whether this money goes directly to their family, a trust, or a monastery.

Bogati points out a key caveat: “The word blockchain is strongly associated with cryptocurrency, which is not legal in Nepal, and not what we are doing. We are using the features of blockchain that make it an excellent system of digital registry.”

THE ARTISTS

As an artist, Sundar Shrestha says the Himalayan Art Council initiative inspires hope especially because it is finally about paying royalties.

“This is a new concept in traditional art,” says Shrestha, who notes that his Newari traditional artist forebears painted their whole life, often with no recognition and remuneration.

Over the lifetime of a body of work through multiple re-sales, the royalty system could make traditional art more worthwhile as a profession, and get more Nepali artists to take it up.However, Shrestha admits that the traditional system also has its merits, and will not go away very soon. He says, “Artists are incredibly focused on their work, because they have to be. Collectors and sellers understand art markets in Nepal and abroad much better than we do, and they bring in regular work that gives us an income and keeps us from starving.”

Part of the skill of a collector is the exhibitions they hold or the relationships they cultivate in high society, which they want to have some secrecy about, says Shrestha, who plans to use both channels to sell his work.

The Himalayan Art Council’s digital initiative would also remove the taboo about talking about the price of traditional art. “Sometimes a student’s painting might sell for higher than the master’s, which can be disrespectful.” Says Shrestha. “And the general sentiment is that paubha are sacred and should be a meditation and a discipline, and that artists are not in it for commercial reasons.”

writer