Epicentre of hunger

Despite improvement in maternal and child survival, malnutrition is rife in Nepal’s western mountainsTo understand the new wave of migration from the remote mountains of western Nepal, one just needs to look at the nutrition status of its children.

Hara BK’s 2-year-old son has an abnormally distended belly, his arms are thin — the result of insufficient food from fallow farms in this rugged and arid region of Nepal.

“Nothing grows here, I’m tired of walking to the health post,” the mother of two tells us, showing the nutrition packet the baby was given. “He gets better as long as we feed him the packet, then he is hungry again.”

Child marriage is still common in Bajura, and Hara was 15 herself when her parents married her off. By 16 she had her first baby. She is unable to produce enough milk for her baby, but already pregnant with a third child.

Nearly 90% of women in Bajura are malnourished. Says ward chair Ajay Kumar BK: “Children born to malnourished mothers also become malnourished.”

Geeta BK is 30. She has six girls aged 15, 12, 8, 6, 5 and 3, and a son who is 1. She tells us, “I had a baby every other year. There is no milk for this one.”

In remote districts like Bajura, child marriage, multiple births, unspaced birth all lead to malnutrition in mothers who then cannot provide enough nutrition for their babies.

“It is a vicious cycle of malnutrition and poverty,” says nutritionist Uma Koirala.

Hara and Gita’s husbands are seasonal migrant workers who go to Dehradun in India six months a year to work as labourers. During that time, the wives are doubly burdened.

Hazari BK, 23, of Muktikot village is severely undernourished, but has to raise a seven-year-old son and two-year-old daughter. She gave birth to her first child at 17, and two of her babies died young.

“This small girl is getting better but I could not breastfeed my son,” says Hazari, who is pregnant again.

NUTRITION PROGRAMS

The government has been implementing a ‘multi-sectoral nutrition plan’ in six districts including Bajura since 2013, involving education, agriculture, drinking water and sanitation, and local development ministries. The current phase of the program covering all local governments aims to reduce stunting to 15% by 2030.

A ‘Nutrition Assessment and Gap Analysis’ conducted in 2009 recommended that agriculture, education, local development and health should all play a role in addressing malnutrition.

Then in 2011, Nepal joined the global campaign ‘Scaling Up Nutrition’ (SUN) campaign, and a year later the government approved the multi-sectoral nutrition program which is still running with support from the European Union, UNICEF, the World Bank, the World Food Program, Canadian Aid, JICA, and the World Health Organization.

Similarly, USAID’s Suhara program which started 11 years ago took nutrition programs to the remotest corners of the country. And while the program has been scaled back after USAID stopped, Hara and Gita are a stark reminder of how past programs have failed.

Public health expert Mahesh Maskey sees a deeper malaise here. This is not a health issue, but linked to state neglect of education, agriculture, gender and food security.

HUNGER FIGURES

According to the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2022, malnutrition has dramatically declined nationally, but not in western Nepal.

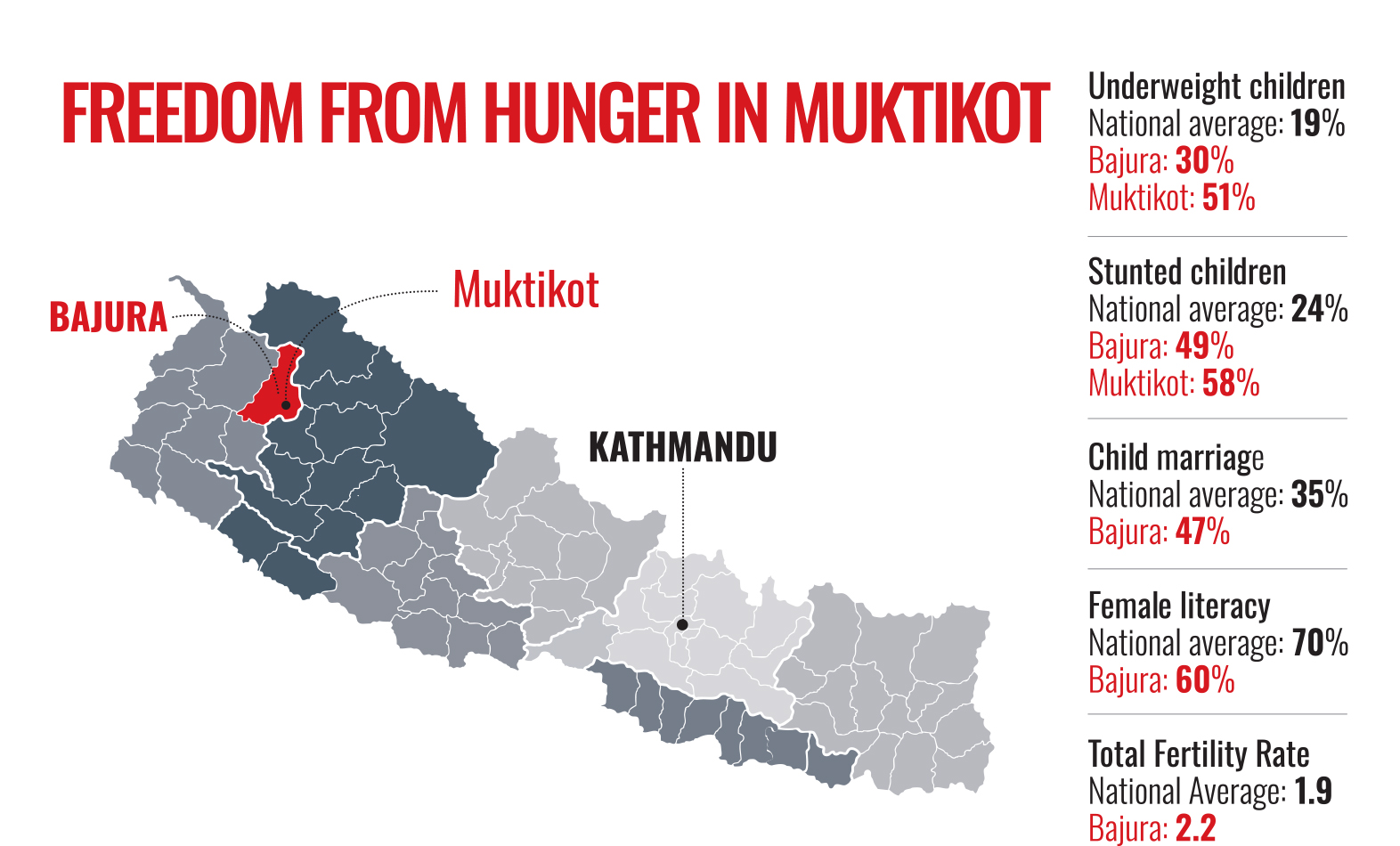

A quarter of under-5 children in Nepal are stunted, but here in Muktikot village the proportion is a shocking 55%. The figure for Bajura district is almost double the national average with 49% of children too short for their age due to a lack of food.

The survey also showed that 19% of under-5s are underweight. Here in Muktikot that percent is 51.2%. A third of the children in Bajura weigh below normal.

Bajura does have nutrition programs, but there is lack of coordination between various government departments with unnecessary duplication of haphazard efforts.

“There is no accounting of who is doing what, how much food is being distributed,” admits Bajura public health officer Kumar Neupane. “This in turn is increasing dependency and reducing local food production.”

Health posts give out ready-to-use therapeutic food to severely malnourished children as a nutrition boost, but this is not a long-term solution. “These items are only supplementary, not substitutes for home-cooked meals,” says Lila Bikram Thapa at the Department of Health Services in Kathmandu.

The World Bank’s recent Nepal Development Update 2025 states that in Madhes Province, delayed monsoon rains hurt paddy yields.

Economist Keshav Acharya says that although funds are allocated for nutrition in the budget, its distribution system and identification of needs are not scientific: “If the target group is not reached and the program is not continuous, such programs are meaningless.”

Malnourished children do not develop adequately mentally and physically, preventing them from rising above the poverty line. Nutritionist Aruna Upreti says that the government multi-sectoral nutrition program has failed due to misplaced priorities.

“Even in remote villages, noodles and biscuits are easily available but nutritious food isn't,” she says. “The use and promotion of local nutritious crops should supersede dependence on external food aid.”

Centre for Investigative Journalism - Nepal