Nepal GenZs inspired Filipinos

Visuals of youth-led unrest in Kathmandu energised protesters in the Manila last monthOne is an archipelago, the other is landlocked. But the Philippines and Nepal have a lot in common: both are disaster-prone, their economies dependent on overseas migrant workers, both went though Maoist insurrections that failed to replace a feudal order dominated by political dynasties. And both countries suffer from rampant corruption.

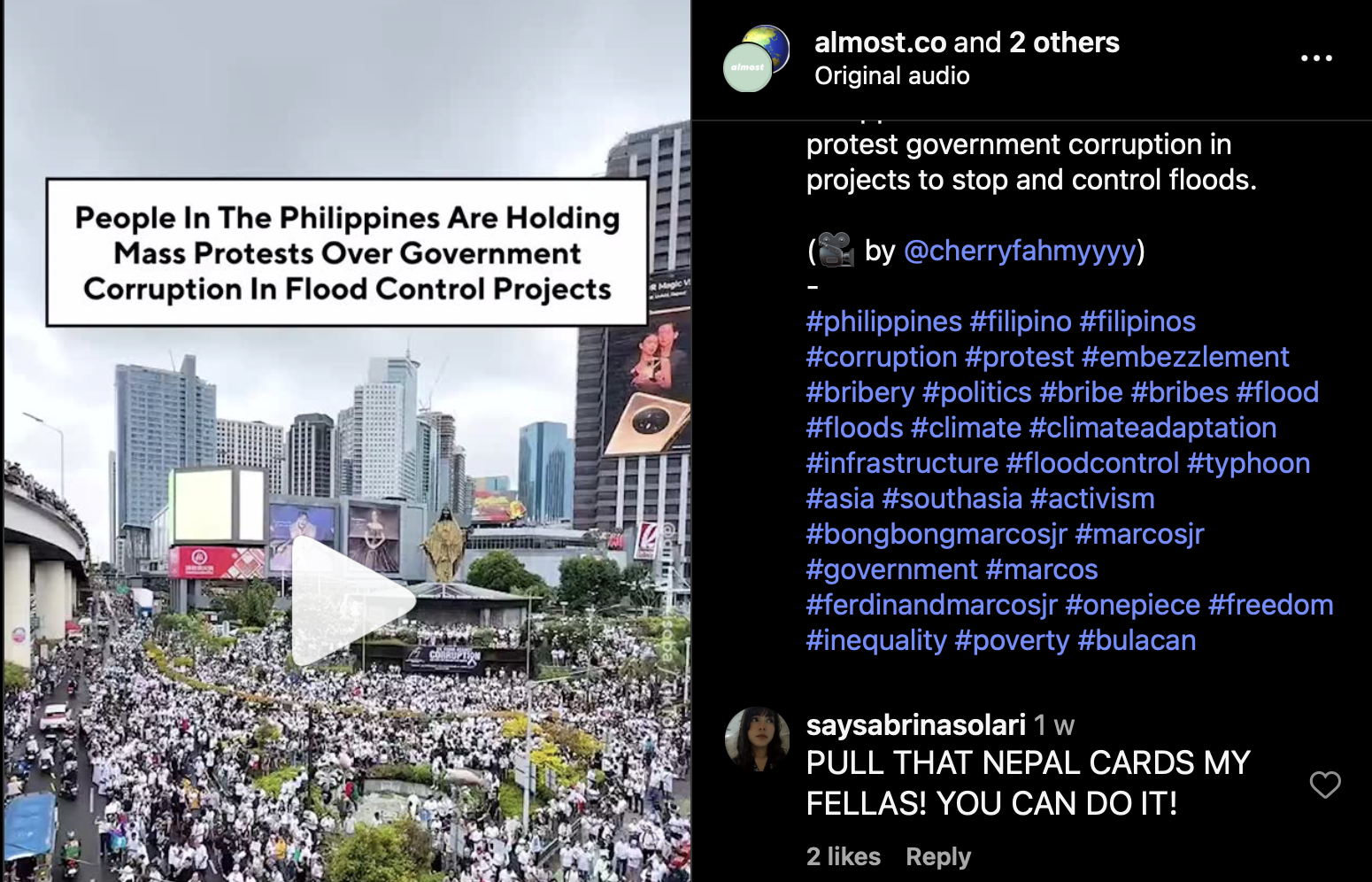

Twelve days after deadly protests toppled Nepal’s government tens of thousands of Filipinos, many of them youth, also poured out into the streets demanding transparency and better government. Cars were set on fire, and more than 200 people were arrested, nearly half of them minors.

The ‘Trillion Peso March Against Corruption’ was fuelled by anger over embezzlement by politicians and their crony contractors estimated to top $17 billion in flood control infrastructure that were either never completed, or non-existent.

“We learnt from Nepal and Indonesia how to deploy social media as a tool to spread information, we are digital natives and well connected within the country and across borders,” said Yuri Lemana of the Youth Alliance for Freedom of Information, and a part of the GenZ protests.

“The system has failed us, unemployment is on the rise, there are shrinking opportunities for youth, and we face environmental threats. There is a realisation that our future is at stake,” Lemana added.

Online groups started highlighting bribery and kickbacks in July after President Ferdinand (Bongbong) Marcos Jr himself brought up corruption in the infrastructure budget in his annual address to the nation, and launched a probe.

The protests gained traction after powerful visuals of rallies in Indonesia and Nepal circulated on digital platforms. Filipino journalists also exposed the high-flying lifestyle of contractors involved in siphoning off the infrastructure budget.

As in Nepal, the youth protests were joined in by various radical groups. In Manila they reportedly included supporters of ex-president Rodrigo Duterte who is currently on trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Hague for extrajudicial killings during his ‘war on drugs’ 2011-2019. Duterte still has a lot of support, especially in the Filipino diaspora, for being tough on crime.

Duterte was allied with Marcos in the 2022 elections, and his daughter Sara Duterte is currently vice-president. But the two families had a massive falling out, and the Supreme Court annulled the Lower House’s attempt to impeach the vice-president.

This week in Manila, a remarkably well-informed Grab driver replayed TikTok videos of Kathmandu’s burning Parliament building to a passenger from Nepal. After his garment factory was driven out of business by cheap Chinese imports, he started driving a ride-hailing cab and was livid with successive governments not providing opportunities to ordinary people like him.

Traffic was gridlocked because of flooded streets, and the driver vented out his anger: “Look at this. The streets are always flooded because of corruption. We should have done here what you did in Nepal.”

Even before the protests, Senate President Francis Escudero and House Speaker Martin Romualdez had both resigned over the 'Floodgate Scandal'. Romualdez is Marcos’ cousin and is now said to be in Madrid, where his every movement is being tracked by Filipino diaspora in social media posts. The Independent Commission for Infrastructure has issued subpoenas to probe corruption in flood control projects.

As in Nepal and Indonesia, much of the anger was over the offspring of politicians extravagantly flaunting their ill-gotten wealth on Instagram and TikTok. In the Philippines, the outrage is also over political clans passing on electoral seats to offspring.

The 21 September protests were centred around Rizal Park and the EDSA Intersection in Manila — both symbolic for previous people’s movements against the Spanish colonialists and the 1986 uprising against the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos (father of the present president).

“People here had seen what happened in Nepal, and were asking why we weren’t as angry as people there? Why not show our anger, too?” said one reporter who covered the protests.

But, he added: “Let’s not be naive. It may have started with youth anger, but there were also people who were paid to infiltrate and instigate. We were also wary that things should not get out of hand like in Nepal.”

Seventy percent of Filipinos are Millennials and GenZ of voting age, and they were impatient with a rigged electoral system. In a clear parallel to what happened in Kathmandu two weeks earlier, radical groups, political rivals, and the general public furious with the system all joined in the protests.

Catholic priests, people from all generations and professions had participated in the EDSA Uprising against Marcos in 1986. This time, it was the youth who took the lead.

Joseph Francisco Ortega of the Philippine National Youth Commission said he understands the frustration among the youth that fuelled the unrest. The discontent is also because despite there being young legislators, they are either party-affiliated or scions of political dynasties.

“If we can convince young politicians to do the right thing, then we have won half the battle,” Ortega said. “If we want to rebuild quickly and for the long term, we have to change the system from within. There is a constructive way to do this, while exercising the right to non-violent protest.”

CROSS-POLLINATION

The violence in Manila streets on 21 September was nowhere near the scale of what happened in Kathmandu on 8-9 September, but both transcended GenZ to be an outlet for pan-generational rage much like 1986 in the Philippines.

“With due respect to the youth, it is not about age but about technology,” explained journalist Malou Mangahas of the Right To Know, Right Now Coalition who participated in the 1986 uprising against Marcos. “We were all young and angry once. We are older, but still angry, and demanding good governance, transparency and accountability.”

Just like in Nepal, young Filipinos rallying against corruption were also wary of infiltration, and it was clear from the anti-Marcos graffiti who the instigators of violence were. The GenZ were mainly wearing white while the pro-Duterte crowd are seen in videos in black.

The minors seem to have just joined in the melee from their street-side settlements. Rights groups have called for their release, accusing police of rough interrogation and ‘red-tagging’ as Communist provocateurs.

Much of the transboundary cross-pollination of anti-government protests across Asia last month used gaming characters, memes, and anime personas like the manga cartoon One Piece flag depicting a grinning skull in a straw hat which became an icon of youth protests.

Yuri Lemana adapted a saying of gaming character Archmagos Cortiko in Warhammer 40,000: “Prayer has its power, but fury also has its uses. If the government tries to hide things from us, we will find a way. Fury will find a way.”

Kunda Dixit is the Publisher of Nepali Times, and was a foreign correspondent based in Manila in the early 1990s.