Covid crisis can spur digitisation

The Covid-19 crisis has accelerated the digitisation process of government services from telehealth to telework, online meetings to remote education. Rarely in modern history have we seen so many virtual experiments in governance around the world rolled out at such a pace and scale.

Industrial age governance, which dominated public sector organisations in the past century acted as a drag on digital transformation. But the pandemic has hastened the shift towards a digital economy.

Nepal’s own Digital Nepal Framework (DGN) came into the policy radar during the tenure of Yubaraj Khatiwada who held the two important cabinet portfolios related to the agenda- Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Information and Communication Technology.

After Khatiwada was appointed ambassador to the United States, apart from one-off progress , focus has not been on tougher issues of fundamentally re-engineering public service delivery and institutionalising digital services. The momentum has therefore been lost on planning for a digital framework, addressing the digital divide between municipalities and inadequate digital skills, the lack of governance framework, and absence of champions in the government.

The DGN requires strong inter-departmental ownership, which it has yet to receive. It has not been popular with senior bureaucrats, and department bosses because it tramples on their fiefdoms. The steering committee organised to take it forward is under-resourced, and extrapolates the DGN framework document as a replica translation of an IT plan developed to strengthen public service delivery in the country.

Whilst digital and IT are not the same, the DGN is designed to establish an overall superstructure for digital services, often requiring a high-level view of interactions among people, process and digital infrastructure.

Says Faris Hadad Zervos, country director of the World Bank for Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka: “As Nepal responds to the Covid-19 crisis, digital development will play an even greater role to build back better, decrease inequality, increase access and opportunity.”

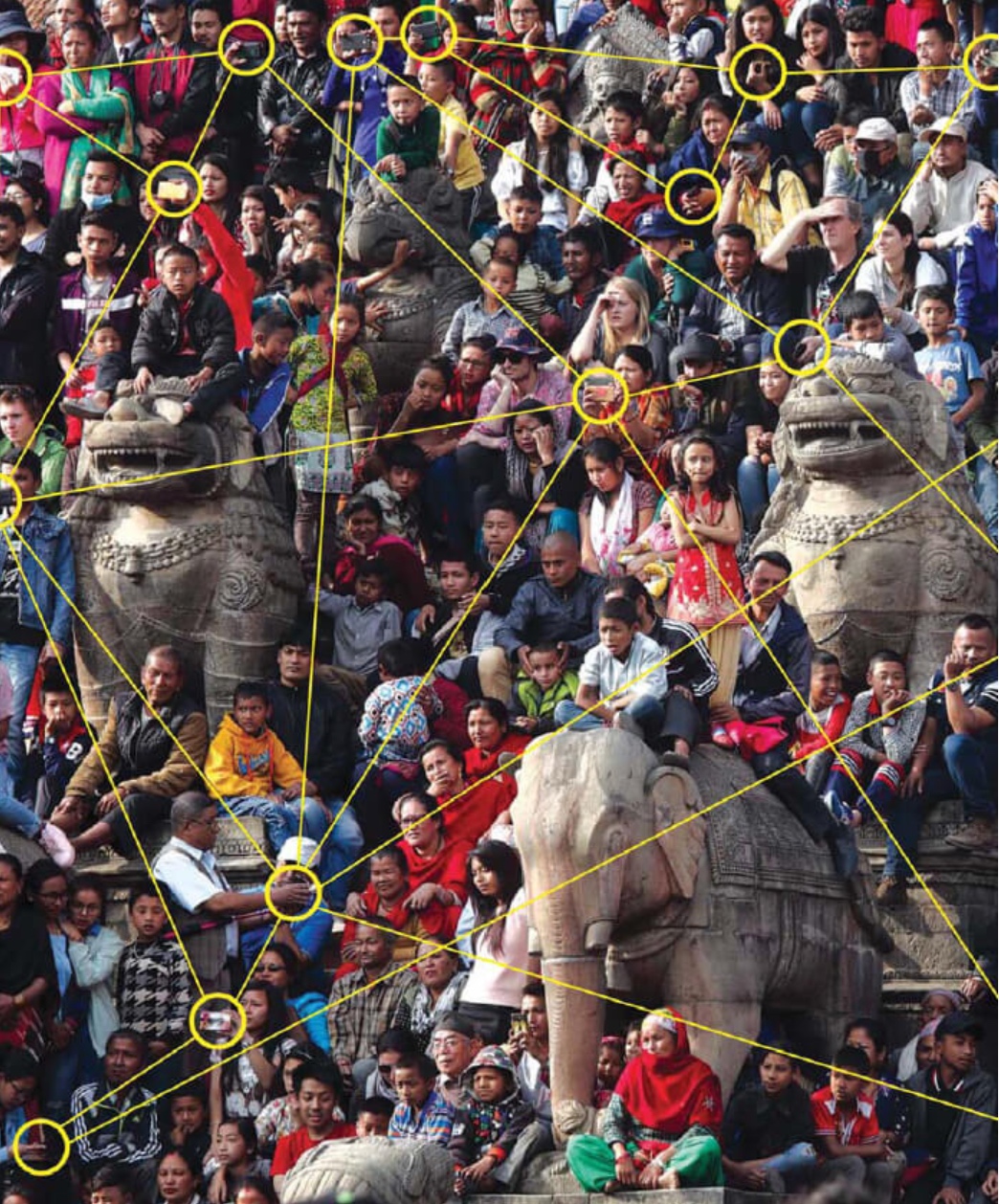

Very few subnational governments in Nepal today have the required digital infrastructure. The magnitude of the challenge is evident as a survey of 115 local governments showed that many rural and urban municipalities lacked internet access or electricity via the national grid or generators”

Most local governments do not have enough fiscal cushion to finance digital connectivity and rely on federal and provincial contributions. Persistent federal-municipal divide is therefore not helping digital transformation. These limitations will hinder future connectivity, and widen the digital divide.

Effort will need to go beyond infrastructure, however, to also provide enough incentives to government agencies/actors, businesses and households to connect with the full range of digital services. National and local leadership will need to address existing barriers to adoption, such as the lack of digital skills and capabilities.

Institutionalising digital services can help the government improve delivery of health and education in geophysically diverse Nepal to ‘build back better’ after the pandemic, thus supporting social inclusion and decentralisation in the young republic. In addition to an inclusive economy, digitising government services can make the country attractive to foreign investors.

Although Nepal has a relatively high Digital Adoption Index and a modest Global Innovation Index in its peer-group, the use of digital signatures, and governance framework considered as the bedrocks to advance digitisation of government services is at a nascent stage. The UN E-Government Development Index 2020 ranks Nepal 132nd among 193 countries on e-government development.

Of course, it is not realistic to expect that the government will leap-frog to higher levels of digital maturity overnight. Institutionalising new technologies and digital governance will require coordinated action between the government, development partners and the societal ecosystem as a whole.

The post-pandemic reality will require the Nepal government to take a policy and regulatory lead in digitising services. The government will have to lead by example synchronising an enabling environment for e-payment systems, telehealth, demand for digital services, including online education.

We must not let the past shackle us and move confidently ahead to implement transformational change in state services through digital processes. As Yuval Noah Harari says: ‘Future historians will see Covid-19 as a turning point in the history of the 21st century. But which way we turn is up to us.’

For Nepal, as immobility grips the economy and traditional processes are disengaged, it is fitting to ask if the government will cling to the past, or advance towards a bold new digital future.

Ashutosh M Dixit is an economist based in Nepal.