Fatal discrimination

A new study in Nepal has found that more female babies die after the third week of birth than male ones.

Even though more male babies die in the first week after birth, the survey points to how gender discrimination may be disproportionately claiming the lives of girl children.

The findings have larger implications for Nepal’s target to reduce the Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR) to 12 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030 as per the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). At present, the figure stands at 21.

Neonatal mortality is the death of a child between 0- 28 days of birth. It can be categorised into early (0-7 days) and late neonatal death (7-28 days). NMR is an important indicator of maternal and newborn health, which shows a country’s quality of life.

Generally, male children are at an approximately 20% greater risk of succumbing to neonatal mortality than girls. Several factors associated with higher neonatal mortality among male children include intrauterine growth restriction, respiratory distress syndrome, prematurity and birth asphyxia.

Animal model studies have shown that testosterone suppresses the immune system, while oestradiol and progesterone in females improve immune responses which means they are better able to fight infections. Data from high-income countries reveal that it is true not only during the neonatal period, but later on in life as well.

In low and middle-income countries males are at a higher risk of mortality in the early neonatal period but more females die in the late neonatal stage. But the specific age (days) where this reversal takes place was not previously known.

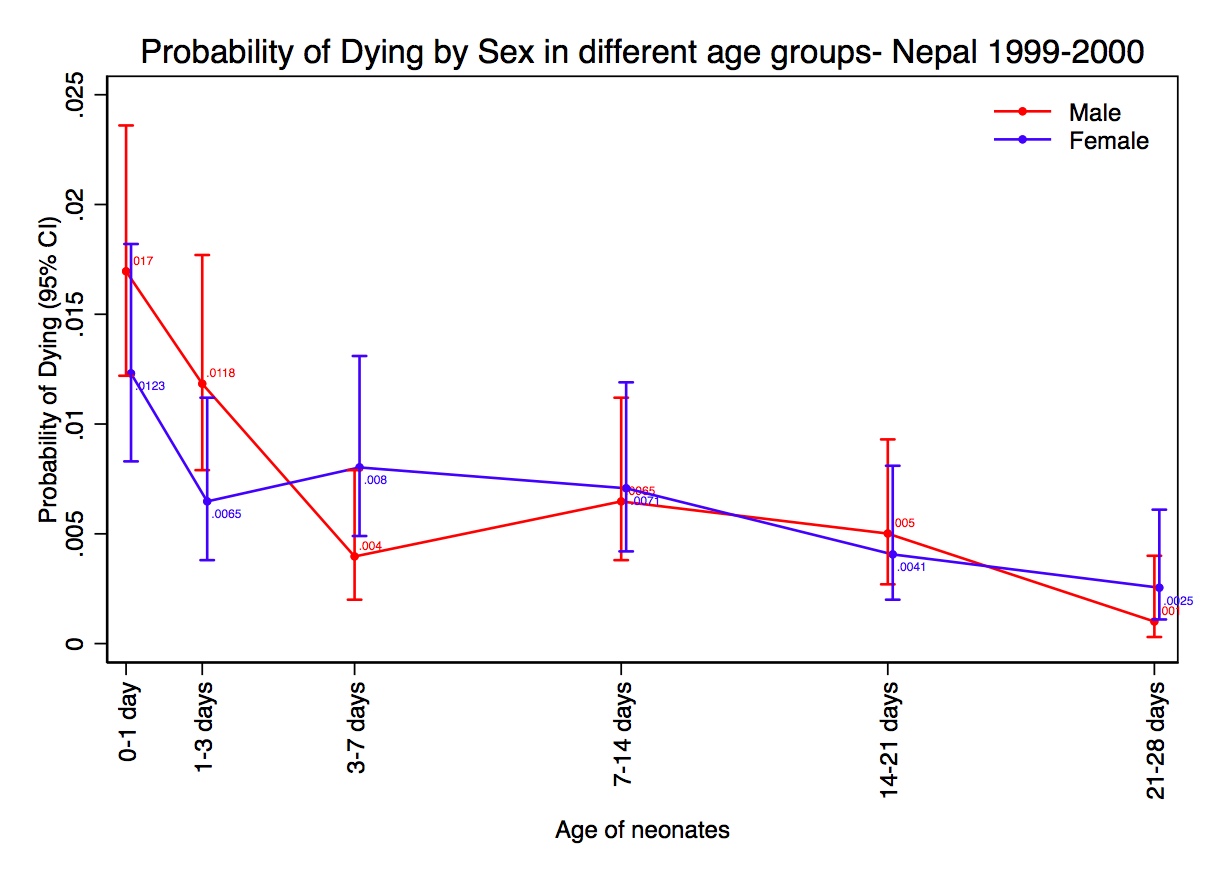

Which is why we conducted a study to examine sex differentials in neonatal mortality by detailed ages (0-1, 1-3, 3-7, 7-14,14-21 and 21-28 days). This is the first study to look at the sex differentials by such granular ages.

We looked into data from three sequential, community-based randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in Sarlahi district of the southern plains of Nepal. The studies provide pregnancy cohorts from 1999 through 2017.

Neonatal mortality was 41.9 (44.2 vs 39.7 in boys and girls), 30 (30.5 vs 29.6 in boys and girls) and 31.4 (33.4 vs 29.4 in boys and girls) in 1999, 2002 and 2010 studies respectively. A common finding in all three studies was that male mortality was higher in the early neonatal period (0-7days), but there was a reversal after the third week of life (21-28 days), where female mortality was higher.

Data from the three studies were combined and analysed with average neonatal mortality coming to 31.6 (33.0 vs 30.2 in boys and girls). When we break this down to sex differentials in mortality by granular ages, male mortality was 1.17 times higher in the early neonatal period. However, this natural pattern was quickly reversed after the third week when female mortality was 2.43 times higher.

This begs a question: why this reversal?

Our paper does not examine the reasons, but studies in South Asia have found higher care-seeking behaviour for male neonates than females, particularly in households with older female siblings.

Moreover, for male babies, care-seeking was more frequent with better-qualified care providers and higher expenditure compared to that of girls.

Studies have also shown that households with female children were more likely to report discrimination because family members perceived that care for illness was not so important leading to reduced care-seeking.

Nepal has been categorised to have a high level of son preference ever since the 1980s in World Fertility Surveys. Not much has changed since then as proven by a 2012 survey where 90% of 1,000 Nepali men aged 18-49 years said that a man with only daughters was unfortunate, and not having a son reflects a lack of moral virtue.

Nearly half of them said that a woman’s important roles were limited to taking care of her home and cooking for her family.

Nepal’s patrilineal and patrilocal social structure combined with socio-economic and religious values lead to son preference and gender discrimination. Traditionally, sons have been given certain cultural and economic roles such as the lighting of the funeral pyre, continuing the family lineage and providing old-age economic security for their parents.

This places them above girls who are considered an economic liability because they have to be married off and with a dowry. And upon marriage, they become part of the economy of the husband’s family.

Given the social norms, the baby survival differential may be explained by poorer nutrition, care and rest provided to mothers giving birth to daughters, son preference being the root cause of discrimination in the family. It could also point to specific parental behaviours that take place starting at that age (21-28 days of a child’s life).

However, the 3-week threshold could also just be an indication that the gender discrimination starts from birth or even earlier, but takes at least three weeks for the biological and natural survival advantage of females to be overcome by the social advantage of males.

Neonatal mortality in Nepal has continued to decrease from 39 to 21 per 1,000 live births, with male neonatal mortality decreasing from 52 to 24 (reduction of 28 per 1,000) and female neonatal mortality from 43 to 17 (reduction of 26 per 1,000) from 2001 to 2016.

Given that boys have a biological disadvantage in neonatal survival, one would have expected female neonatal mortality to decrease significantly over time. A reduction in female neonate mortality would also mean an overall decrease in neonatal mortality. But as it is, it is unlikely Nepal will meet its target of reducing NMR to 12 by 2030.

Gender discrimination not only affects the quality of life of girls and women, but also reduces their survival in the neonatal period. A cross-national study from 138 countries also showed that higher the gender inequality index, higher the neonatal mortality of a country.

Read more: Saving one mother at a time, Bikash Gauchan

Addressing gender discrimination by removing cultural and social barriers at the household level may help reduce overall neonatal mortality.

Interventions to strengthen gender equality, such as counselling women and their families during antenatal and postnatal care visits may significantly improve female and male neonatal survival.

Since the reversal takes place during the fourth week, specific interventions should be targeted in the first three weeks of a child’s life.

Seema Subedi is Faculty Associate in the Global Disease Epidemiology and Control Division of the International Health Department at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, USA.