RED ALERT: Get ready for the wildfire season

How Nepal can reduce forest fires and boost farm production at the same timeChronic winter drought and decades of unmanaged forest biomass have turned wildfires into a systemic risk for Nepal. We need to re-learn to convert fire fuel in forests into fertilizer for crops.

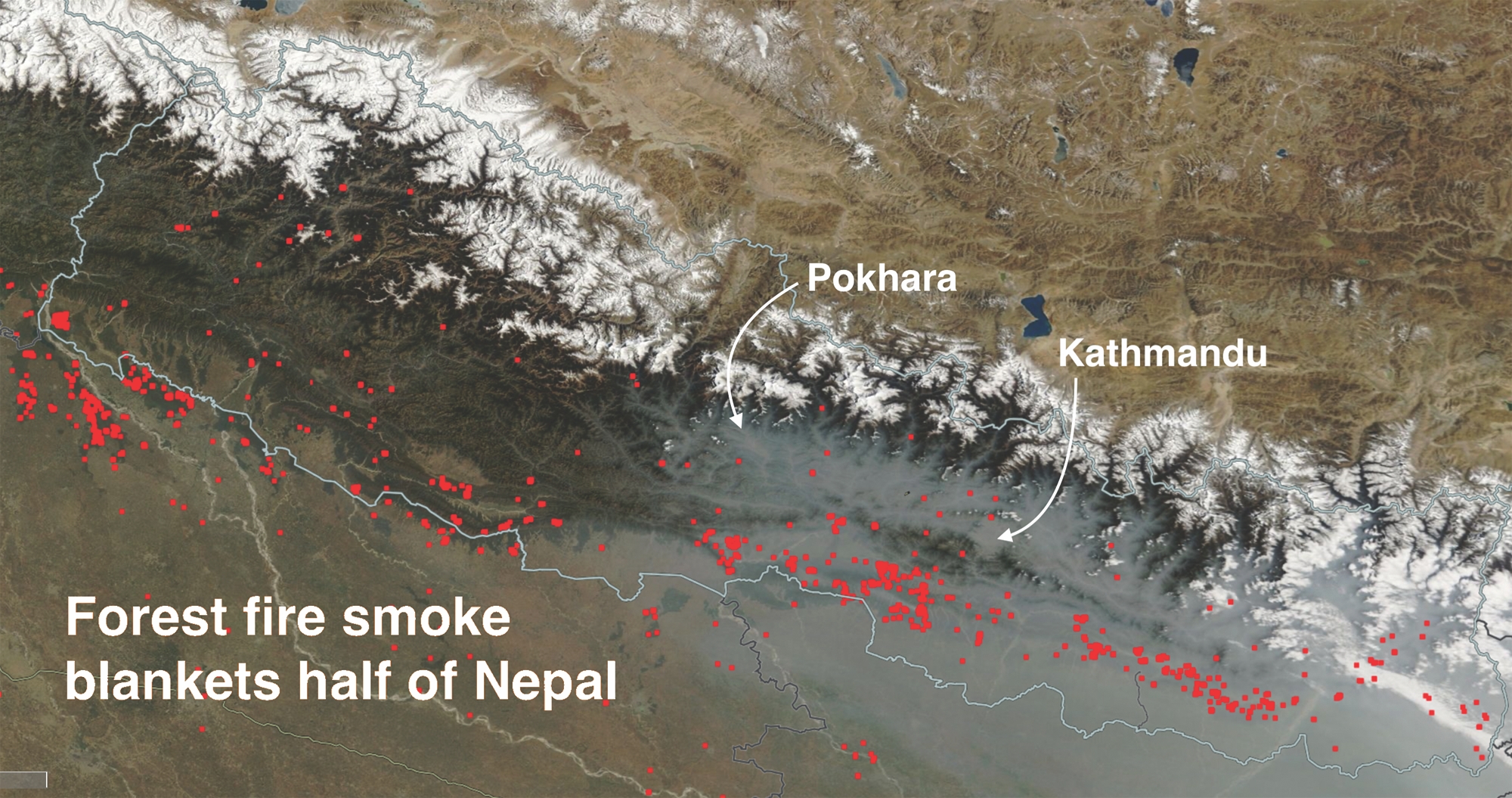

On 11 January, a huge forest fire spread rapidly from China into the forests of Sindhupalchok, 40km northeast of Kathmandu. The newly-opened Tatopani border checkpoint was closed. Smoke from the fire spread across central Nepal, blocking the sun.

The fire burnt itself out within a few days, but the border stayed closed for longer. Such wildfires were once rare in mid-winter, and traditionally peaked between March and May as temperatures rose ahead of pre-monsoon showers.

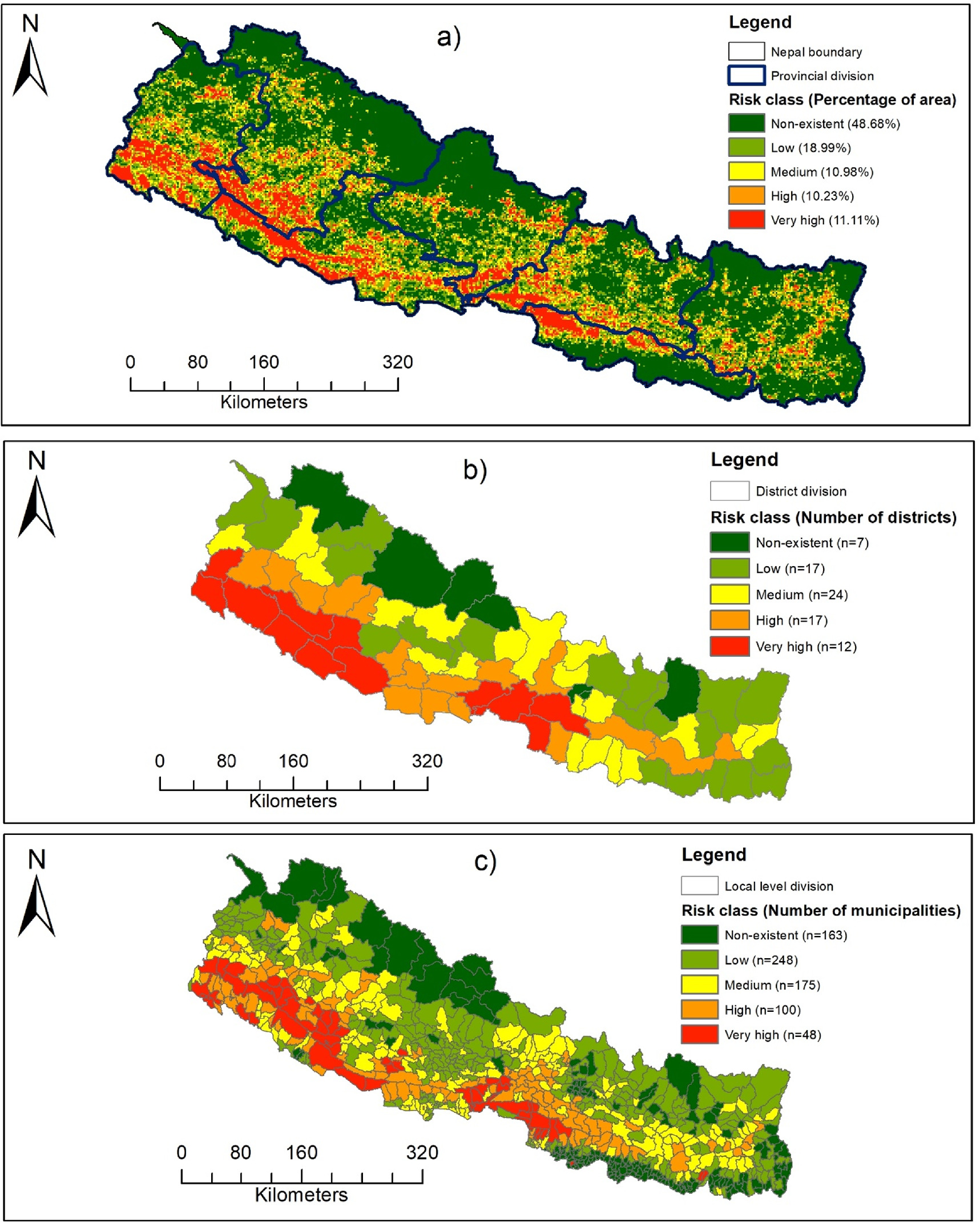

What is unsettling is not just the early onset of the fires, but also their scale. This shift is not accidental, the pattern has been unfolding over years due to winter drought, weakening post-monsoon moisture, and the accumulation of dry forest biomass as Nepal’s forest area doubled in the past 30 years.

Together, these factors have made forests tinder dry in spring, just waiting for a spark. Nepal has experienced winter drought in eight of the past ten years (this winter was an exception). Winter rain and snow at higher elevations play a decisive role in maintaining surface moisture, recharging shallow aquifers, and keeping forest floors damp enough to resist ignition. When winter rains fail, forests dry out months earlier than usual.

Satellite-based assessments show a steep decline in surface moisture across the middle mountains of Nepal, particularly in areas with dense forest cover but limited undergrowth management. Springs that once flowed year-round are now seasonal.

More than half of the springs in the mid-hills have either dried up or show significantly reduced discharge, a trend closely linked to declining soil moisture and disrupted recharge zones. Dry soil does not just threaten water security — it helps the vegetation ignite.

FUEL WITHOUT FUNCTION

For decades, Nepal’s forests have been accumulating dry leaf litter, fallen branches, shrubs, and deadwood. Historically, this biomass was not considered waste because rural households regularly collected leaf litter for livestock bedding, which was later composted and returned to farms as fertilizer.

Forest floors were therefore relatively clean while the mulch fertilized farms. That relationship has steadily eroded due to outmigration, changes in livestock systems, restrictions on access to community forests, and the growing availability of chemical fertilisers.

Community forests across the country today are thick with dry twigs, branches and leaves — a highly combustible carpet. When prolonged drought dries this biomass, even a small spark from a herder’s intentional fire, a cigarette, or lightning strike can trigger massive fires.

Under such conditions, the question is no longer whether fires will occur, but how intense and widespread they will be. Forest fires are often framed as an environmental issue concerning trees and wildlife. In reality, their impact extends far beyond forest boundaries.

Smoke travels faster and further than flames. Fine particulate matter, especially harmful PM2.5, spreads across countries. In recent fire seasons, air quality monitors in Kathmandu have recorded air quality levels several times higher than WHO guidelines. The smoke adds to Kathmandu’s own pollution and lingers for days.

Flights are cancelled or delayed in cities like Pokhara, and poor visibility blocks mountain views affecting tourism. Health facilities report spikes in respiratory complaints, particularly among children and the elderly. Just as wildfires have multi-sectoral causes, the impact of forest fires go beyond forests.

One critical dimension remains largely invisible: the soil. The fires cause silent damage beneath the ash, and the emergency does not end when the flames subside. Beneath the surface, soil suffers long-term damage. Organic matter burns away, beneficial microorganisms die. The soil structure weakens, reducing the land’s ability to absorb and retain water. The scorched earth is more prone to erosion, increasing the risk of floods and landslides once the rains return.

In many of Nepal’s agricultural areas, soil organic matter levels are already below 2% -- lower than what is needed for resilient and productive farming. Repeated fires push these levels even lower, undermining soil fertility and forcing farmers to rely more heavily on chemical fertilisers, unleashing a vicious cycle of higher costs and food insecurity.

Climate breakdown is often cited as the primary culprit, and rightly so. Rising temperatures and erratic rainfall have intensified fire risk. But fires in Nepal are increasingly the result of human intervention.

The response of all three levels of government remains too little, and too reactive. Each year, resources are mobilised to extinguish fires once they have already spread. Far less attention is paid to managing the fuel load within forest undergrowth that makes such fires inevitable.

Meanwhile, forestry and agriculture policies are not coordinated, missing opportunities to address shared challenges. Forest fires are not natural disasters, but predictable outcomes of governance choices.

National plans and climate pledges set an ambitious target of raising soil organic matter to 4%. The science behind this goal is solid. Higher organic matter improves water retention, stabilises yields, reduces fertiliser dependence, and enhances long-term food security. What remains unclear is the pathway.

Where will the organic inputs come from? How will they be processed and applied safely at scale? Without practical answers, the 4% target risks remaining aspirational rather than achievable.

Forest undergrowth can be turned into fuel and fertiliser. Biochar is produced by heating organic biomass in a low-oxygen environment, converting it into a stable form of carbon that can be added to soil.

When properly produced and applied, it improves soil structure, enhances water and nutrient retention, supports microbial activity, and locks carbon into the ground for decades.

In Nepal biochar addresses two interconnected problems: reducing the accumulation of combustible biomass in forests, lowering fire risk, while simultaneously rebuilding depleted soils. In doing so, it restores the broken link between forest management and agriculture.

Done well, biochar is not merely an environmental intervention. It is an economic one, with potential to create local employment, reduce farmers’ input costs, and support climate-smart agriculture.

But biochar propagation depends on improved governance. If promoted as isolated pilots or short-term projects, it will fail. What is needed is institutional clarity: standards for production and safety, quality control mechanisms, farmer extension services, and coordination across local, provincial, and federal levels.

Community forest user groups could manage biomass collection. Local governments then support safe, decentralised production units. Agricultural extension services guide farmers on application, linked to soil testing and monitoring. Such an approach would reduce fire risk, improve soil health, and generate rural livelihoods.

Poorly produced biochar or contaminated feedstock can harm soils and human health. Without training, standards, and oversight, good intentions can backfire.

Nepal needs to move beyond fire-fighting to fire prevention and confront the structural causes that make them a growing risk. It is not just a technical choice – it is one that demands political will from newly-elected leaders after March.

Ngamindra Dahal is a hydrometeorologist with the Nepal Water Conservation Foundation specialising on climate and water management issues.