East - West City

The narrow strip of plains that used to be a dense jungle till 70 years ago was cleared to resettle mountain farmers and turn it into Nepal’s rice basket. Today, it has become an east-west swathe of asphalt and concrete with neither paddy fields nor forests.

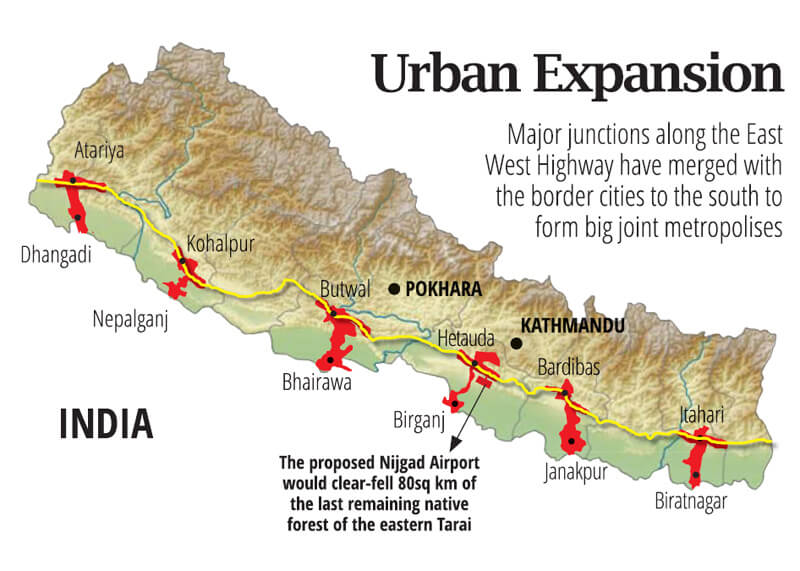

Major junctions along the East -West Highway have merged with the border cities to the south to form big joint metropolises like Atariya-Dhangadi, Kohalpur-Nepalganj, Butwal-Bhairawa, Bardibas-Janakpur, or Dharan-Itahari-Biratnagar.

From these hubs, urban expansion is also taking place east-west and to the north. It is only a question of time before the present East-West Highway will be a long street running through one big city that covers the entire Nepal Tarai.

“Haphazard settlements have replaced what, till recently, used to be forests and farmlands all along the highway,” says economist Dilli Raj Khanal. He warns that Nepal will face an alarming future if agriculture is in decline in both the mountains because of outmigration, and in the plains because of urbanisation.

Read also: Economy & Ecology of Nijgad Airport, Om Astha Rai

Bardiya beginnings, Lisa Choegyal

On a recent trip across the Tarai, from Jhapa to Kanchanpur, the signs were ominous. In Bara, there is no forest left except for the Parsa National Park, and the farms along the roads are gone too. Chitwan Valley, except for its national park and the thinning Barandabhar wildlife corridor, is just one big city. From Narayangad to Kawasoti, and from Butwal to Dang, there are mostly houses on both sides of the road. From Patlaiya to Nijgad, the only remaining forest may soon be converted into a new international airport. The further east you go along the Tarai, the more houses, and less trees you see.

All this has had a major impact on the East-West Highway that serves as the country’s main transportation artery. It is impossible to drive faster than 40 km/h because of settlements on both sides. The number of highway accidents have shot up, and vehicles killed 80 wild animals in the past year.

Resettlement of farmers in the Tarai began after malaria was eradicated through a US-supported DDT spraying program in the 1960s. King Mahendra then launched a transmigration scheme to resettle mountain villagers in the Tarai, giving away land in the cleared forests.

Read also: Tarai Metropolis, Kunda Dixit

Political ecology of the madhes, CK Lal

After the East-West Highway was built, migration picked up. Today, de-population of the mountain valleys has been accompanied by over-population of the Tarai, at great cost to the environment and agriculture.

Urban expansion northwards from highway towns has put pressure on the Chure forests, already ravaged by quarries mining sand and boulders to be smuggled into India. This has increased siltation of the seasonal rivers that drain to the Tarai and India, triggering flashfloods that have inundated towns, destroyed farmlands, and washed away highway bridges.

Deforestation of the fragile Chure has also lowered the water table which was already in steep decline because of over-extraction for agriculture. Water shortage combined with shrinking arable land has already had a devastating impact on Nepal’s agricultural production.

Mayor Bidur Karki of Bardibas tells us wryly: “Nepalis are migrating to work in the Arabian desert in droves. They don’t have to anymore, there is a desert right here.” In his town, 70% of the wells have gone dry. Pumps that used to strike the water table at a depth of 10m, now have to drill deeper than 50m.

Girendra Kumar Jha is the District Health Officer in Jaleswor, a border town in the eastern Tarai. He says: “I tour the villages to talk about washing hands, and the villagers ridicule me saying first give us water, then come to talk about hygiene.”

Read also: Save nature from politicians, Editorial

Conservation and Tourism, Kristjan Edwards

The diminishing ground water has affected wildlife populations, even inside nature reserves. Most waterholes inside Chitwan National Park that used to have water even in the dry season have been going dry, forcing tigers, rhinos and their prey to migrate. But even that migration is becoming more difficult because forests set aside as wildlife corridors are thinning due to encroachment.

“The jungles of Lothar in Makwanpur used to be famous for rhinos till 20 years ago,” explains Shantaraj Gyawali of Hario Ban Nepal, “now you can only find them south of Sauraha in Chitwan because the watering holes have all dried up.”

Sunachuri in Makwanpur is a scenic town at the base of the Mahabharat Hills. Chandra Shrestha’s family migrated here when he was boy 50 years ago. Back then, he remembers, there were just a few wooden huts. There was thick jungle all the way to the next village of Manahari, 9km away.

Shrestha, now 77, says: “Today, Sunachuri and Manahari have merged into one town. Migration turned into a flood after the East-West Highway was built. And it is getting more crowded.”

Read also: Help save the Chure hills, Tirtha B. Shrestha

Conserving conservation, Sara Parker