Getting high on High Mountain Tea

Rebranding Nepali tea, putting it on the world map

The all-purpose Nepali greeting “चिया खानु भो?” literally means “have you had your tea?” But it can mean anything from ‘Good Morning’, ‘How are you?’, or any other greeting.

Now, mundane tea-drinking is being replaced by a new breed of beverage aficionados who savour and grade sophisticated teas as if it were champagne.

For the untrained palate used to morning tea with milk and sugar, the subtle aroma and flavour of High Mountain Tea brings out the wholesomeness and simplicity of the leaves. Once hooked, many in Nepal and around the world do not want to slurp anything else.

And slurp it you must, as a recent elaborate tea-tasting ritual showed. Speciality teas of the High Mountain have been quietly gaining a loyal international following, proving to be a premium export from Nepal.

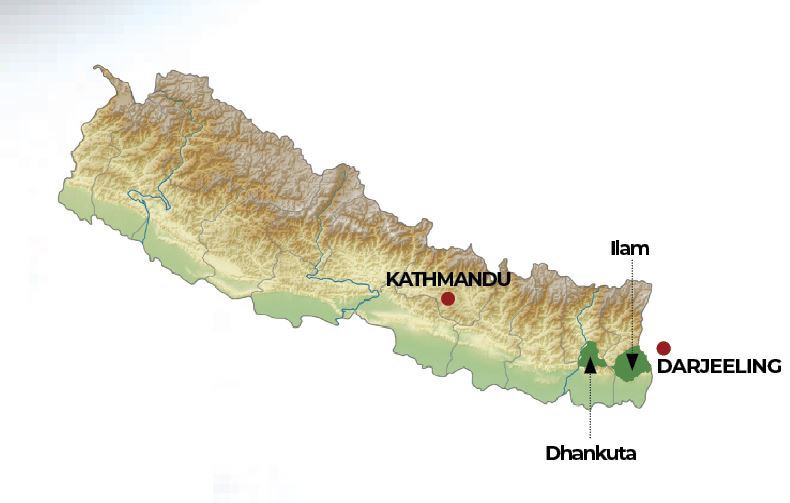

“There is no one way of drinking tea but we have completely rebranded Nepali tea, not just in taste but in our mindset and marketing,” says Lochan Gyawali of Jun Chiyabari, a family-run tea garden 2,000m high up in the mountains of Dhankuta.

Nepali tea is often mistaken for the more popular Darjeeling variety because of similar taste and production methods. Historically, whole-leaf tea grown in Nepal used to be sold in India to be exported and blended into Darjeeling while the rest was processed into cheaper broken-leaf CTC black tea for domestic consumption.

But Nepali growers are now consciously moving away from British and Indian influences, carving a unique Asian identity for tea from Nepal with refined taste.

Speciality tea or ‘orthodox tea’ as it is commonly called, uses the wholeness of the leaf to create a diverse range of flavours. The leaves are not torn or crushed as they are in Darjeeling teas, but carefully rolled to create the desired taste and tang.

Starting this month until December, tea pickers in Jun Chiyabari's 90-hectare plantation on the slopes near Hile in eastern Nepal will be busy, carefully plucking young leaves before they go into processing.

“From the beginning we brought experts from Japan, China and Taiwan to train our staff to unlearn what Darjeeling has been doing,” says Gyawali, who himself grew up among tea gardens next to his school in the hill station.

Unlike the usual tea production, High Mountain goes through withering, rolling and drying with specialised equipment designed to retain the organic compounds that give tea its essence.

“You change the machine, you change the taste. Our teas have become different because of the way we pick them, process them, and the equipment,” explains Gyawali who started Jun Chiyabari with brother Bachan Gyawali after dabbling in the tourism and electronic export sectors.

Jun Chiyabari today produces up to 20 different types of tea, each with its own distinctive flavour. It is exported to the United States, Canada, Japan and Europe where connoisseurs compare the teas to the sophistication of fine wines. The popularity of High Mountains s also growing amongst Nepal’s urbanites, where it is often called ‘chiampagne’.

“If you want to sustain a market like Japan, mediocrity will not sell, you need perfection. Japanese buyers tell us our tea is unlike anything they have tasted from South Asia,” says Gyawali proudly.

Indeed, High Mountain is described in Japanese as having the ‘flavour of the mist of the mountains’ — an accolade of the highest order.

Speciality tea production is not without challenges. Nepal has not even scratched the surface of the potential in the domestic and world market. There are no studies into cultivars suitable for Nepal’s topography. Growers have to rely on trial and error methods.

This means raw material is limited. With additional challenges posed by climate breakdown, growers are having to cope with increased demand and maintaining a delicate balance between quality and quantity.

“We already knew global heating was going to impact us, so the selection of plantation sites was important. We couldn’t do anything about rising average temperatures and precipitation patterns, but we could, and did, go higher up the mountains,” says Gyawali.

The pandemic has also affected Nepal’s tea industry, but enthusiasts have discovered the health benefits of High Mountain during this time and boosted online sales. More and more growers are now interested in this niche market.

Jun Chiyabari’s motto has remained the same over the years, to grow unique leaves to put Nepal on the world tea map. If the praise it has received internationally (see above) so far is anything to go by, it has already achieved this.

Tea Talk

“Jun Chiyabari is a mark of trust and artistic creativity in Japan. All its various types of tea come in amazing quality and with an unmistakable sense of purity that captures the heart of tea connoisseurs.

This is the fruit of constant effort trying to understand tea itself and the market. They are one of the very few producers who have tried and also succeeded in adapting a part of themselves towards the Japanese market.

-Sayaka Nakanoji, Silver Pot Inc, Tokyo

Our connection to Jun Chiyabari tea garden dates back more than seven years. We purchased our first batches in 2014, which was one of the best decisions we have made. Since then our business has flourished and Nepali tea sales are increasing in our region.

We consider Jun Chiabari to be the most progressive tea company in Nepal. In my opinion, they bring Nepali tea to a very high level and bring much fame to the country. Their attitude and care towards co-workers and the surrounding natural environment is a model to be followed in other parts of the world.

We are proudly selling the carefully selected batches from the Jun Chiyabari tea garden to various restaurants and cafés in Budapest, Central Europe, including the finest Michelin star restaurants.

-Gábor Tálos, Zhao Zhou Tea, Budapest

History of Tea

Tea dates back to ancient China 5,000 years ago. Legend has it that Chinese emperor Shen Nung in 2737 BC was sitting beneath a tree with his servant boiling drinking water when some leaves from a tree were blown into it. A renowned herbalist, Shen Nung, decided to taste the infusion. The tree was Camellia sinensis, which came to be known as 'tea tree'.

Over time, tea established its medicinal properties helping reduce stress and fatigue. Before long, tea travelled across Asia via Buddhist monks to Japan, Korea and beyond.

It was only in the 17th century that tea became popular among the British who then introduced tea plantations in India, specifically Darjeeling, to end the Chinese monopoly.

It is only natural that neighbouring Nepal would be the next place to be ‘tea-fied’. The beverage soon took off, influenced by British and Indian preferences for mixing in milk and sugar, and lately, other spices.

But the history of tea in Nepal is not linear. In 1863 the Daoguang Emperor of China gifted tea plants to Prime Minister Jung Bahadur Rana. Tea plantations in Ilam district began shortly after the British set up theirs across the border ridge in Darjeeling.

But tea was consumed in Kathmandu long before that. Newa traders in Tibet had already brought tea drinking to Kathmandu – not with milk, but black tea with salt and butter.

High Himalayan

Harvesting: Young leaves are plucked by tea-pickers between late March and December. Tea makers can decide which type of tea to make depending on their look, the area where they are from and the time when they were plucked.

Withering: Leaves are spread on vast trays to wither, are gently fluffed, rotated and monitored to ensure even exposure to the air. Before withering, some teas go through the sun, wilting out in the open.

Rolling: The leaves after they become limp are rolled either by hand or a machine. This is to break cells and mix together a variety of organic compounds found naturally within the leaves to bring out its flavour.

Oxidisation: The clumped leaves are broken up and set to oxidise, laid out to rest for several hours depending on the style of tea being produced. Oxidisation greatly influences flavours.

Firing/drying: Finally, the leaves are heated or fired quickly to dry them to below 3% moisture content and stop the oxidation process. The leaves can then be stored safely.

Tea Types

Broadly speaking, there are five main varieties of tea in the market:

Black: The most common type of tea, this is fully oxidised, is darker in appearance and has higher caffeine content. It is characterised by a strong flavour and is typically consumed with milk and sugar. Think Darjeeling and English Breakfast.

White: Simply withered and dried, this is the least processed of all teas. Has a high level of antioxidants but the lowest caffeine content. Best consumed without any additives. The infusion is very light-coloured and has a mild flavour. Originally from China.

Green: The unoxidised tea that has retained its natural green colour with a high level of antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals. It produces a pale greenish-yellow infusion with a light and grassy taste. Popularised as a healthy tea, it can be taken with lemon, but not milk.

Oolong: Semi-oxidised tea mainly produced in China and Taiwan with flavour resembling neither black nor green. The aroma depends on how long the leaves are allowed to sit before halting oxidisation. Produces golden or light brown infusion.

Pu-erh: Exclusively from Yunnan province of China known for its distinctively earthy flavour. Made from wild tea leaves rather than cultivated ones, it is fermented by pressing raw leaves together, often stored underground for several years for maturity. Can be either black or green depending on the level of oxidation allowed.

writer

Sonia Awale is the Editor of Nepali Times where she also serves as the health, science and environment correspondent. She has extensively covered the climate crisis, disaster preparedness, development and public health -- looking at their political and economic interlinkages. Sonia is a graduate of public health, and has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Hong Kong.