Replicating Nepal’s stolen gods

It is difficult to get western museums to return trafficked deities, so Nepalis are making copies of the missing statuaryThe discovery that the 12th-century deity stolen from his neighbourhood had turned up in Dallas, Texas, was a bittersweet one for Bhai Raja Shrestha.

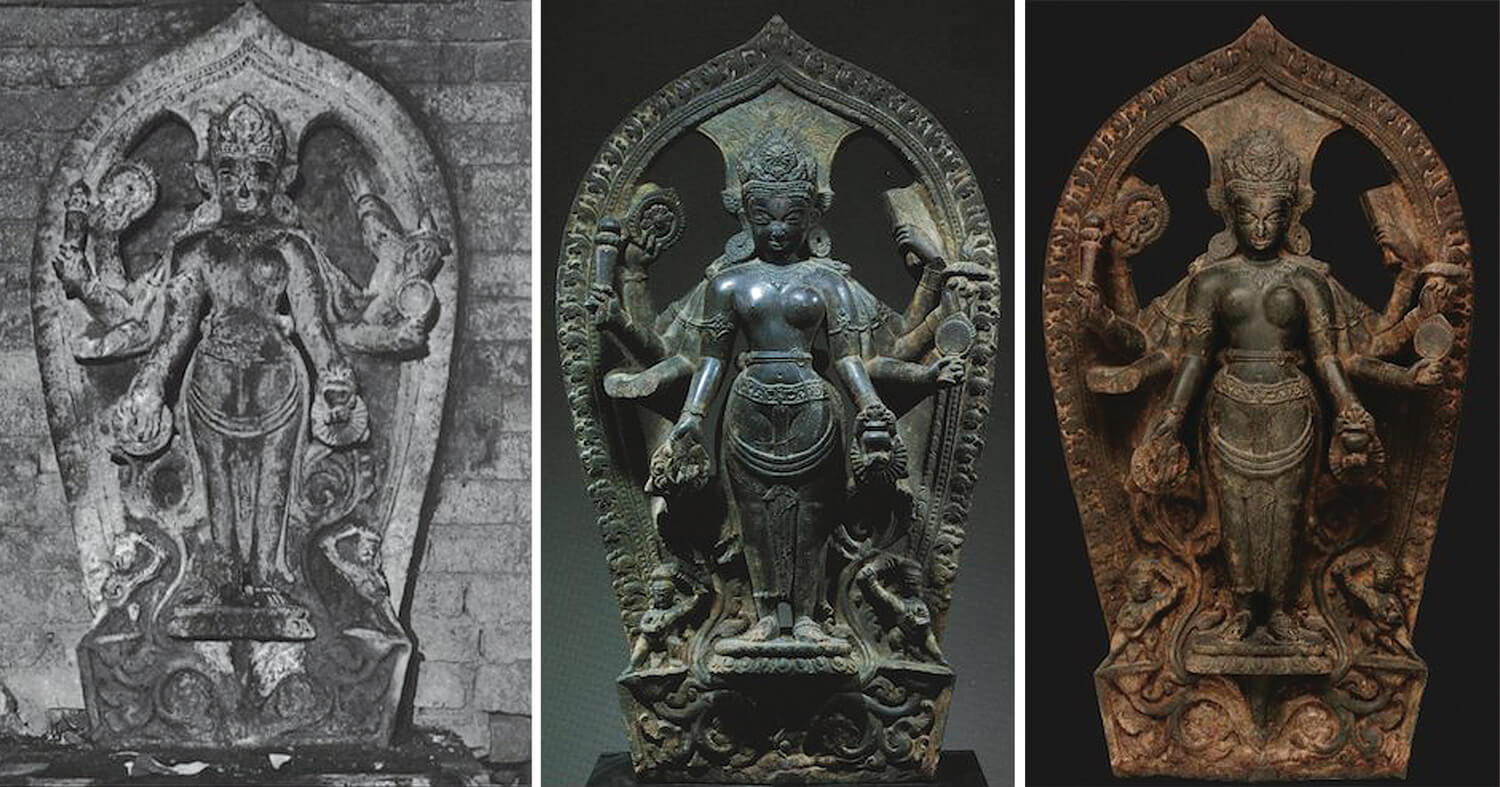

The statue of Laxmi-Narayan was stolen 30 years ago at a time when Kathmandu Valley was being plundered of gods and goddesses by western art collectors. It was recently tracked to the Dallas Museum of Art by American artist Joy Lynn Davis, who has documented Kathmandu’s missing deities through striking works of visual art.

The 700-year-old stone figure was once an integral part of the intangible heritage of Patan’s Patkutole neighbourhood. After it was stolen in 1984 Shrestha says the community also started falling apart.

Read also: Back where they belong, Bhrikuti Rai

“We are glad our god has been located in Dallas. We will try our best to bring it back, but we must also ask ourselves whether we are up to taking good care of it,” says Shrestha, 77, a social activist in the Patkutole neighbourhood of Patan.

Shrestha recalls that the theft was a heart-wrenching moment for the community and especially for those for whom Laxmi-Narayan is a patron deity. “People used to come in large numbers every day to this temple for puja, but after the god was stolen this changed. Now it is a whole generation later and the temple has suffered from the god’s absence.”

Even though the figure was replaced by a poor replica in 1993, and the temple itself renovated in 2006, the neighbourhood does not attach the same importance to it. “God is god regardless of it being a replica or not. However, it does pinch you that the original piece is among foreigners who could not care less about its religious significance,” Shrestha adds.

After it was stolen, the rare androgynous composite deity was sold by the Sotheby's auction house (it was sighted in the Sotheby's catalogue in 1990), and it was later loaned for 30 years to the Dallas Museum of Art by a collector named David T Owsley. After the figure on display at the museum was found to be the stolen Laxmi-Narayan, this was pointed out to the museum by art crime scholar Erin L. Thompson. In response, the Dallas Museum of Art tweeted on 20 November 2019, “The Dallas Museum of Art takes these matters very seriously and we are currently looking into this.” The deity has since been removed from display.

The figure, also called Vasudeva-Kamala, is one of those many Kathmandu Valley deities that find themselves in museums or at auction houses in Europe and the United States. Although the government abides by UNESCO’s international laws on import and export of cultural properties, and has its own Ancient Monument Preservation Act, the process of repatriating stolen antiquities is legally cumbersome.

“The Dallas Museum has to return our cultural property. It is proven that it’s ours, and we are working to get it back,” acting director of the Department of Archaeology Damodar Gautam, told Nepali Times. He admitted the process is tedious: his department has to write to the Ministry of Culture, which will forward the request to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the US Embassy and the Nepal Embassy in Washington, DC, the last of which will take it up with the US government and finally the Dallas Museum of Art.

The Department of Archaeology has a scanty inventory of stolen deities, and does not keep a record of artifacts that have been returned. Its records of the latter say merely that 32 stolen figures have been returned since 1996 (mainly from museums in Europe), from the thousands that have been trafficked by art thieves.

The government’s responsibility to protect Nepal’s living heritage is being filled by people like Roshan Mishra, curator of the Taragaon Museum, who has documented many of the stolen artefacts on his website, Global Nepali Museums. Mishra’s data shows that most of the smuggling has occurred since the 1970s, and 41 museums all over the world exhibit stolen stone, bronze, terracotta and wooden religious artefacts from Kathmandu. These institutions include the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Denver Art Museum and the San Diego Museum in the United States, the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada and many others.

“Our idols are auctioned for millions of dollars abroad and we cannot do much about it because of the long and slow bureaucratic process. The government needs to be more resolute in getting them back, otherwise they will remain abroad,” says Mishra.

Read also: Here today, in Europe tomorrow, Janki Gurung

In 2010, a bronze Garuda water spout, a centrepiece of the Sundari Chok in Patan Darbar Square, was stolen. It was retrieved by police a year later in Kathmandu. Currently, the exquisitely carved 120-year-old figure is on display at the National Museum at Chhauni. A replica bronze created by artisans at the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT) is now at Sundari Chok.

“It was essential that we come up with a solution rather than wait for the statue to return to the original place,” explains Rohit Ranjitkar, director of KVPT, who says that putting the original back would have risked another theft.

Read also:

Good job, Kunda Dixit

Return of the gods, Sujata Tuladhar

Lain Singh Bangdel’s Stolen Images of Nepal (1989) and Jürgen Schick’s The Gods are Leaving the Country (2006), both written by art historians, document the stolen artefacts, and they catalogue what Nepal has lost in past decades. Many of the pieces have been traced to western museums and collectors.

Whether or not to replace the originals with replicas, and where the originals should be housed if they are returned from museums and art collectors abroad, are hotly debated subjects. Some temples in Kathmandu now have replicas, and original deities are protected by iron grills, or are bolted to walls.

Nepal is not the only country that is putting pressure on western museums to return antiquities. Greece and the British museum are haggling over the Parthenon Marbles stolen by Lord Eglin in 1806.

The British Museum is also under pressure to return the stolen Benin bronzes from Nigeria, but is saying that the artifacts are too “fragile and delicate” to travel.

A museum of copies

Bhaktapur architect Rabindra Puri has come up with another way of documenting Nepal’s stolen deities. As part of his Mission Panauti Project, he is working on the Museum of Stolen Arts, set to open in 2022 in this town that has lost many of its religious objects.

The museum will initially have 50 stone replicas of sacred statuary that have been trafficked abroad. So far, artisans have hewn 36 of them.

“All the replicas in our display are of stolen idols that are Nepal’s property and we have clear evidence of this. We need to raise awareness of the theft. It is public pressure and not the lengthy government process that will help us retrieve our heritage,”

Puri says. Puri hopes that the museum will raise awareness among Nepalis and build pressure on western museums and auction houses to return statuary to Nepal.

While appreciative of the effort, KVPT’s Rohit Ranjitkar is not entirely convinced that a museum of replicas will help in the struggle for repatriation. He says: “It is easy to copy them, but there is little chance that international museums will agree to repatriate our deities. Also, even if they are returned, how will we preserve them in their original location?”

If the security of returned statuary cannot be guaranteed in their original locations, returned deities will find themselves in Nepali museums. Ranjitkar sees little value in this.