The saga of Nepal Jaynagar-Janakpur Railway

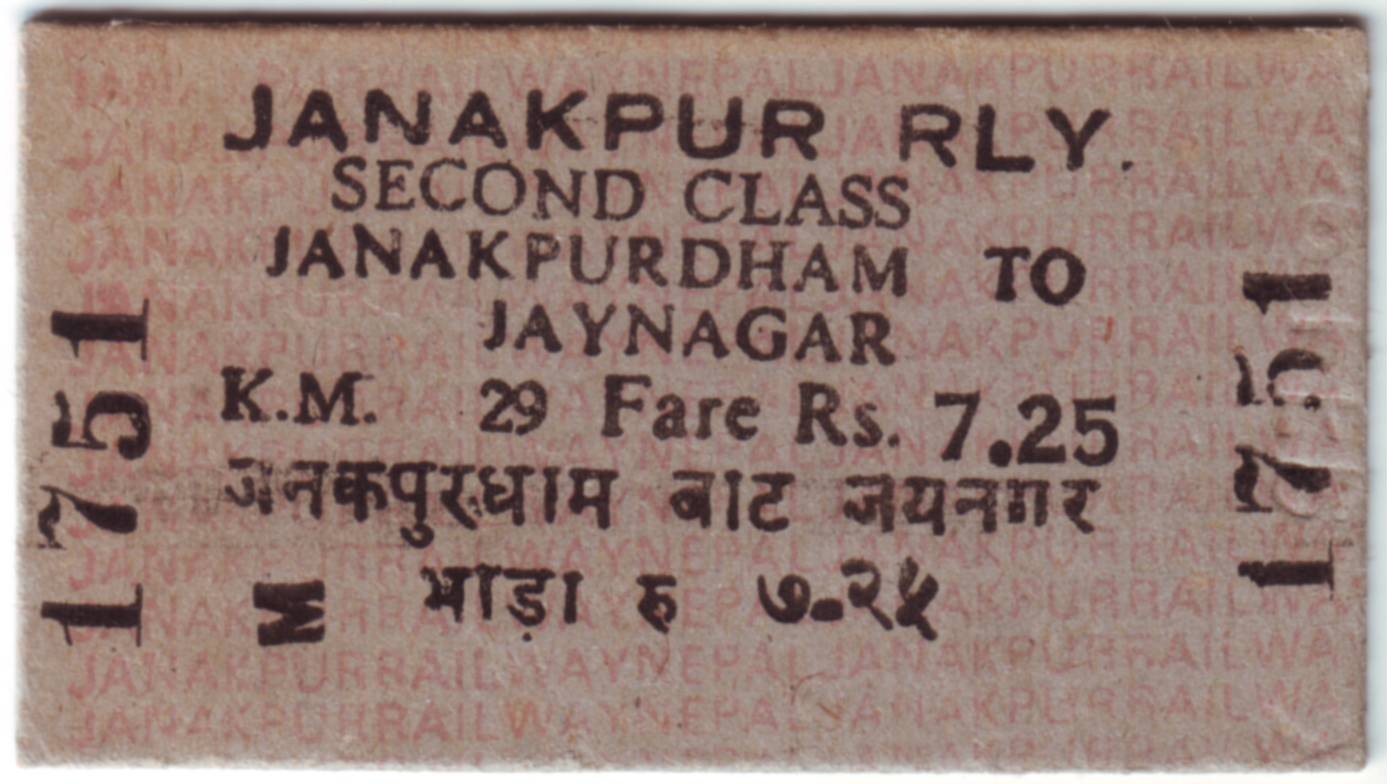

Travelling at 15km per hour in the eastern Tarai for 76 years, the NJJR was a part of Nepal’s historyPrime Minister Juddha Shamsher Rana built the NJJR probably to transport logs cut on his forested birta land north of Janakpur to sell in India. The 2’6” narrow-gauge railway extended north from Jaynagar, India 29km to Janakpur and another 22km to Bhutaha/Bijalpura, cost 680,000 Indian rupees to build, and opened for business December 1937.

The Nepali engineer in charge of construction was Capt Tilak Bahadur Rayamajhi, who in 1908 was one of the first Nepalis to receive a civil engineering degree in India.

After 1950, the line from Janakpur to Bhutaha had little commercial value and was out of service.

Until the late 1970s, there were no proper motorable roads connecting Dhanusha and Mahottari Districts with India. The NJJR was the only transportation alternative for people who had to otherwise go on foot, bicycle or ox carts to India.

The NJJR also played an important role in religious tourism, as hundreds of thousands Indian pilgrims visited Janakpur annually to participate in the Bibaha Panchami, Rama Navami, and Janaki Navami. For the Bihari peasant bound for Janaki Mandir in 1955, sitting on the roof of a slow-moving train was a luxury compared to trudging 29km on foot from the Indian border.

The first manager of the NJJR in Janakpur was Lt Hem Bahadur Gadtaula-Chhetri. The general manager from 1942-58 was Rekha Bahadur Rayamajhi of Bhojpur, posted at the railway’s main office at Jaynagar.

Rama and Seeta, the railway’s first two appropriately named locomotives, were built in Berlin in 1936. In view of the rising power of Adolf Hitler’s Germany at that time, was Prime Minister Juddha trying to cultivate the Third Reich in hopes of reducing Nepal’s virtually total dependence on British India?

In 1939 Adolf Hitler gifted a Mercedes-Benz 230 Pullman Landaulet to Juddha as a way to convince him not to let the British use their Gurkha regiments against Germany in World War II. The car had to be disassembled and carried over the mountains to Kathmandu and reassembled.

The Nepali Congress-led campaign against Rana rule received considerable support in Janakpur and the eastern Tarai. In December 1951, King Tribhuvan rode the NJJR from Jaynagar to Janakpur, and thousands thronged to catch sight of a king of whom they had heard but never seen.

As operations on the Nepali Government Railway came to an end, its European-made engines were transferred to the NJJR. King Mahendra ordered two more locomotives named Chandra and Surya for the NJJR in 1962. They were built in Leeds and traveled from Liverpool to Calcutta to Jaynagar to begin their service.

The NJJR was renamed Janakpur Railway (JR) in 1965 and became the Nepal Railway Company in 2004. Unlike most government-owned enterprises in Nepal of that era, the JR and Nepal Government Railway operated at a profit for many years. In 1947, its total income was 225,000 Indian rupees, with a profit exceeding 100,000 rupees.

In FY1974/75, the railway had revenues of 2.6 million rupees and a profit of 443,000 rupees. It is unclear if depreciation expenses were accounted for. Only from the mid-1980s did the railway begin to lose money.

The NJJR did a booming passenger business. Ridership increased from 197,000 in 1960/61 to 1.4 million in 1977/78. Revenue increased from 770,000 rupees in 1966/67 to 2.6 million rupees in 1974/75. Yet warning signs appeared in the 1970s that the railway was living on borrowed time.

A foreign consultant conducted a comprehensive study of the railway in 1975 and concluded that ‘the entire railway is very old and worn out, and unless a total rehabilitation’ of the railway was undertaken, it would ‘be forced to close in a very short time’.

CHUGGING ALONG

An investment of two million rupees resulted in some improvements between 1976 and 1979 but rolling stock and most infrastructure were neglected for another 15 years. Yet somehow the JR’s trains kept chugging along for the next 42 years, often late, with service frequently suspended due to floods.

Nearly every year, monsoon rains swept away some of the 135 bridges and tracks and embankments. An RSS News Agency bulletin in August 1975 noted that parts of Janakpur were ‘under 2.5 feet of water’, and the railway tracks near Khajuri were covered by four feet of water.

The Jaynagar line was damaged in many places by the swollen Jaladi, Kamala and Jamuni Rivers. Trains to Bijalpura were suspended. For each week railway service was suspended a loss of 75,000 rupees resulted.

There were also accidents. Trains made only two or three roundtrips daily between Jaynagar and Janakpur and ran at slow speeds, so there were few passenger fatalities, but there were frequent derailments due to the worn rails and overloaded carriages. A RSS report in 1976 said a train derailed near Mahinathpur, and some passengers riding on the roof fell off and were injured.

‘Such accidents occur because the coaches are not regularly maintained and repaired. The speed of the train has been reduced from 12 to 8 miles per hour, since the old and rickety coaches rattle and sway from side to side if driven too fast. The trains take an incredible 4 to 5 hours to cover 28 kilometres,’ the report noted.

Gangs of dacoits occasionally boarded trains and robbed passengers. Another RSS report in December 1972 said ‘Six dacoits armed with guns and revolvers looted 13 railway passengers travelling from Janakpurdham to Jaynagar [last] Sunday. The [loot] included wrist watches, gold rings, currency notes and other paraphernalia of the passengers…The dacoits raided third-class bogie number 2 soon after the train started from Khajuri station. The dacoits after plundering the passengers jumped down from the running train about two miles from the Nepal-India border [and fled into India.]’

Strikes and political protests also stopped the train from time to time. From the early 2000s Maoist and Tarai-based groups enforced stoppages with threats and intimidation that closed schools, shops, government offices, and brought transport services to a halt. Six minor political parties organised a strike in Janakpur in May 2001. Agitators stopped a train near Janakpur and pelted it with stones, breaking windows and injuring the driver.

The railway came to a standstill in May 2004 after Maoists set fire to the Mahinathpur station. During February-March 2006, the Maoists obstructed rail service six times. A cylinder bomb exploded inside a train near Parbaha station in May 2009 injuring 30 passengers.

Between 1993-2003, the railway had nine general managers who had influence with Kathmandu’s political and bureaucratic elites, but none of whom knew much about railways. Management was unable to control rising payroll and administrative costs nor secure adequate funds for the railway.

Revenue ‘leakage’ was significant, as perhaps twenty percent of the passengers rode without tickets. Railway staff was bloated, in 1996 there were 340 on the payroll, many of them with political connections who needed jobs. Safety measures for railway operations were non-existent.

There were no performance reviews, no criteria for promotion, and no training opportunities for workers to improve their skills. But the locals continued to ride their beloved railway.

For 56 years, the Janakpur Railway received no foreign assistance, not even one rupee of foreign aid. That changed in 1994 when the Indian government provided two used diesel locomotives and 12 used coaches. Two years later, India supplied two more engines and 12 more coaches and promised some upgrades.

This gave the railway a new lease on life, but the road network in the eastern Tarai had expanded,making the railway redundant. It also did not connect with the East-West Highway, the major transportation artery across the Tarai, nor could it seamlessly interconnect with India’s broad-gauge rail network at Jaynagar.

The railway carried no goods, all cargo traffic migrated to trucks. During the 1980s and 1990s, British and European train spotters traveled to India to ride its few remaining steam locomotives, including those of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Some took a side trip to Jaynagar where they, without Nepal visas, were thrilled to ride a train to Janakpur without encountering a border check post or immigration officials. Other visa-complying tour groups arranged steam trains for 60,000 rupees or more.

The last steam excursion ran in 2006, and after that, foreign interest in the railway evaporated. Cascading financial losses and government indifference coupled with irregular, unreliable service finished on the Janakpur Railway.

Seventy-six years of remarkable narrow-gauge railroading in Nepal ended not with a bang but a whimper on January 20, 2014. Sic transit gloria.

Dan Edwards was a Peace Corps volunteer in 1966 and is the author of several books on Nepal. This is the third instalment in a new limited series in Nepali Times on the historic transportation infrastructures of Nepal.