Map land

Exhibition showing the evolution of Himalayan and South Asian cartographyOne aspect of colonial cartography of South Asia leaps out in this must-see exhibition – while the coastline of India, Ceylon, Burma are extraordinarily accurate in maps made more than 200 years ago, the Himalayan hinterland is wholly approximate and inexact.

The accuracy improves as modern survey techniques are introduced by atlas-makers, but even then formidable terrain and forbidden lands thwart precision.

Map aficionados will be fascinated by the 40 antique maps from The Rajbhandari Collection on display at the exhibition ‘Imaging South Asia: Nepal in the Making at Kathmandu Art Gallery’ at Baber Mahal Revisited from 13 February - 17 March.

The first maps were made on clay tablets and cave paintings, but maps improved with Chinese maritime charts of Southeast Asia and beyond. Nautical maps created during the European Age of Exploration used geometry, latitude and longitude.

Competition for colonial riches rested on the accuracy of these maps. The Portuguese had the lead in the 15th century, but were soon overtaken by the Spanish with Columbus voyaging to India but landing up in the Americas.

European mapping of the coastline of peninsular India began after Vasco de Gama sailed around the Horn of Africa to arrive at what is now Kerala in 1498.

The British and French struggled for control of India, and the Carnatic Wars of the 19th century were extensions of their rivalry in Europe.

While most of the maps at this exhibition were commissioned by the East India Company and the Survey of India, there are quite a few made by Parisian cartographers and feature Pondicherry and the Danish trading outpost at Tranquebar.

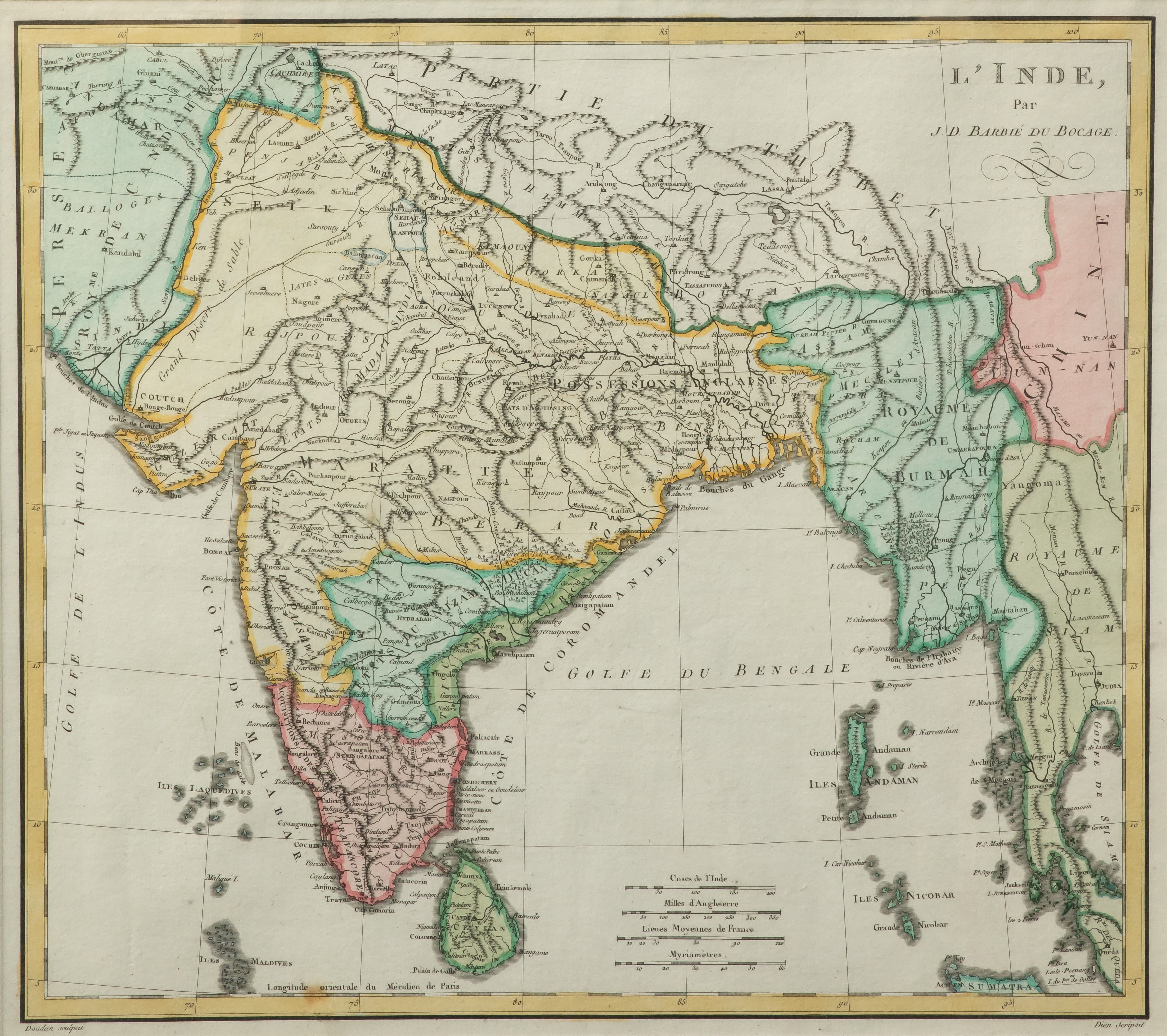

Followed chronologically, the maps show improvements in cartographic techniques. The earliest French map L’Inde of J D Barbié du Bocage from 1760 is a copper engraving with hand painted colours demarcating boundaries. ‘Napaul’, ‘Gorka’ and ‘Catmando’ are depicted.

The rivers of India are precisely drawn, as is the Brahmaputra (Yarou Tsanpou) even though locations across the rest of Tibet are rough estimates.

The 1781 map Carte des Indes en deçà et au-delà du Gange of Rigobert Bonne has slightly more detail about Nepal with even ‘Pattan’ and ‘Bagmally’ river marked. William Darton’s 1802 map has ‘Nogarcot’ and ‘Mocaumpour’ wrongly placed to the east of the valley of ‘Napaul’.

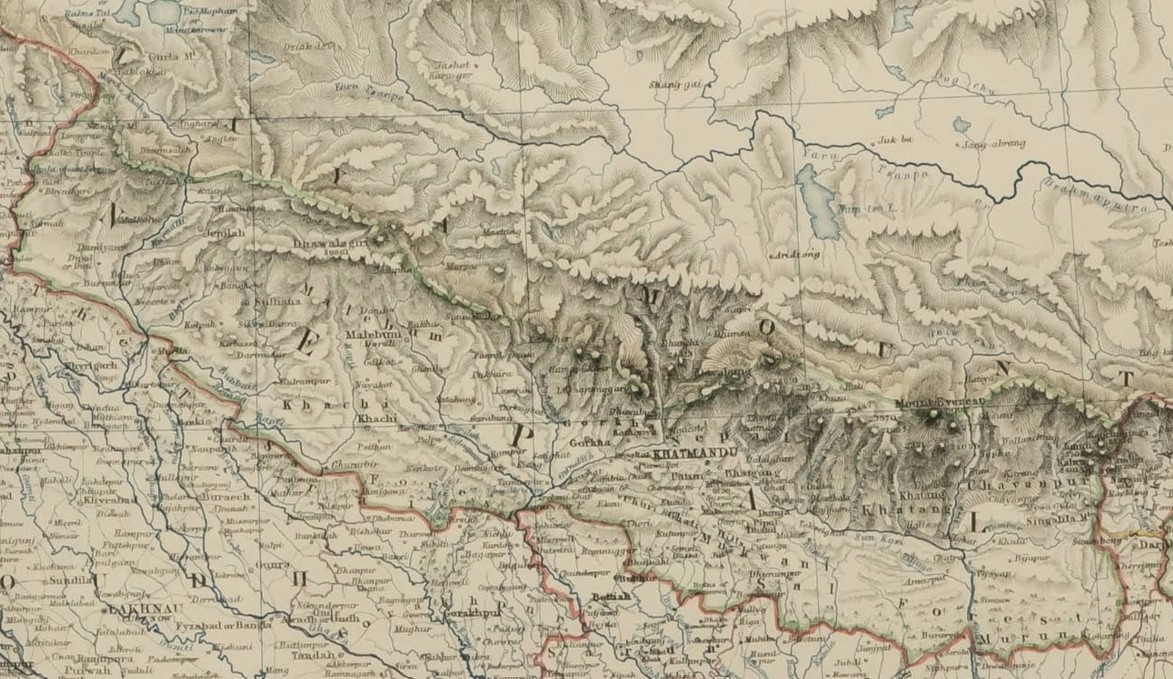

Samuel Arrowsmith’s 1828 map ‘India and the Birman Empire’ has Nepal’s rough boundaries demarcated for the first time within a hand-coloured green border, with the mountain ‘Dholagiri’ and ‘Dhunchi’ appearing for the first time.

The 1835 map by Boston-based American cartographer Thomas Bradford has a more precise ‘Burrampooter’ river with ‘Sgigatoe’, ‘Lassa’ and ‘Bootan’ marked. In Nepal, ‘Batgan’, ‘Macwampour’ and ‘Lelit Pattan’ appear near ‘Catmandu’.

One striking landmark appears consistently through a century of map-making from 1760 onwards, and that is the sacred Yamdrok Tso near Lhasa. It is precisely located, although it is drawn as a circular lake called ‘Jamdro or Palto Lake’ till J Bartholomew’s lithographic map in 1893 Constable’s Hand Atlas of India.

Bartholomew’s map is also where ‘Mt Everest’ appears for the first time with its altitude ’29,002ft’ after Peak XV was calculated to be the highest mountain in the world by the Survey of India. Meanwhile, ‘Kinchinjunga’ appears in some of the earlier maps from the mid-1800s, north of ‘Dorjeloo’.

The maps did not only have locations of towns, rivers and mountains but also other interesting facts about places. History buffs will find much to pore over in these maps.

Many have sites of major British battles while conquering India. The ‘British India’ map by J Rapkin has dates and times of the ‘Principle Massacres’ during the Indian Mutiny of 1857.

The map also shows India’s growing railway network with completed lines and those ‘in progress’. Narrow gauge lines can be seen in successive maps snaking up to the Nepal border to haul sal logs for sleepers for India’s expanding railway network.

Many maps were drawn by British military intelligence. One even has the Kuti route of the Nepal Army while invading Tibet in 1791, and the Chinese Army’s advance in hot pursuit through Kerung to Nuwakot.

Pre-1857 maps show the western Tarai as a part of British India, but in later ones the Naya Muluk districts of Banke, Bardia, Kailali and Kanchanpur have reverted back to Nepal.

The maps clearly mark Nepal as an independent nation, and represent it differently from Indian princely states. The Atlas of India of 1846 shows the ‘Dominion of the King of Nepal’.

Visitors will be curious about Nepal's claim to Limpiyadhura and Lipu Lek. A map by Mason & Payne from 1846 clearly shows the ‘Kallee River’ as being the border between Nepal and British India, with Kalapni within Nepal. The Lipu Gad tributary (which India claims is the border) is not marked.

Some other maps, however, seem to show the border not following the Kali river to Limpiyadhura but the tributary up to Lipu Lek.

Imaging South Asia: Nepal in the Making

Kathmandu Art Gallery, Baber Mahal Revisited

13 February – 17 March

For guided walk-throughs

and curatorial tours: +977 1-5318048

Panel discussions:

-Cartographic Practices from the Gorkha Polity to the Present

with Buddhi Narayan Shrestha and Kanak Mani Dixit

Friday, 13 February, 4pm

-Mapping Beyond Borders

with Akhilesh Upadhyay and Amish Raj Mulmi

Wednesday, 25 February, 4pm

writer

Kunda Dixit is the former editor and publisher of Nepali Times. He is the author of 'Dateline Earth: Journalism As If the Planet Mattered' and 'A People War' trilogy of the Nepal conflict. He has a Masters in Journalism from Columbia University and is Visiting Faculty at New York University (Abu Dhabi Campus).