Missing the plot in Nepal's job scheme

For most Nepalis, the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic far outweighs its health risks. The majority of Nepal’s population is employed in the informal sector, cannot work remotely and have no social safety net.

With many parts of the country going into another lockdown this week, any hope for employment recovery has further evaporated. Amid the uncertainty and financial distress, Kathmandu saw an exodus of tens of thousands of Nepalis fleeing back to their villages, a familiar scene from last year.

The 2020 budget set an ambitious target of creating 700,000 jobs and raised public expectation. Some 200,000 of these jobs were to be created through the Prime Minister’s Employment Program (PMEP), a work guarantee scheme launched in February 2019 that promises 100 days of employment to the jobless.

The numbers, however, paint a bleak picture. A whopping 752,976 jobseekers registered themselves as unemployed in the past year, of which 42% were women (see Figure 1). However, only 78,678 of them landed jobs for a combined 843,042 days so far this fiscal year. This translates into an average of 11 days of employment (see Figure 2). Even if we take underreporting into account, the numbers severely fall short of what was promised. In the first two years of the program, an average of 13 and 16 days of work was provided.

Ganesh KC, Mayor of Madhuwan Municipality in Bardia, sees two merits of PMEP. The financial respite brought to those who receive jobs, albeit for a few days. And how it has concurrently helped with the maintenance of roads and public infrastructure.

But he notes that there is significant room for improvement. “The number of jobseekers overwhelmingly exceeds the jobs available and those who get employment only do so for a few days. This results in disappointment as we raised public expectations with this scheme,” he says.

The Employment Coordinators (ECs) in charge of PMEP implementation appointed at the local administrative units also echoed this view. “There is fatigue among jobseekers to fill out forms year after year when they don’t see results. They put pressure on the local representatives who in turn put pressure on us. This has put a dent on our credibility,” says one EC. While registered unemployed who were not provided jobs are entitled to 50 days equivalent of unemployment allowance, it hasn’t come to fruition yet.

Suman Ghimire, Joint Secretary at the Labour Ministry and National Program Coordinator of PMEP, sees lack of local ownership as a big hurdle in PMEP implementation.

“There is still a lack of understanding among local officials and representatives on the significance of PMEP which puts it in the backburner. They need to proactively engage with ward officials on the significance and implementation of the program as implementation begins at the ward level,” he says, adding that hiring and retaining ECs has been challenging in remote areas. “Without ECs at each municipality, it is difficult to expect results.”

This discrepancy in local ownership is evident in a recently released PMEP 2019-2020 report, according to which only 495 out of 753 local units managed to implement the proposed projects, even though the budget was disbursed to 701 local units. So far this year, 566 local units have implemented PMEP (see Figure 3).

As per the report, PMEP intended to provide 100-days employment to 60,000 jobseekers 2019-20. Of the 370,734 who registered as unemployed, 105,365 got jobs for an average of 16 days. Only 39 local units provided jobs to over 500 individuals. Of the 753 ECs to be appointed at each local unit in charge of overseeing the PMEP implementation, 110 local units did not have ECs either because they had not been appointed at all or had resigned, which was further delayed by the pandemic.

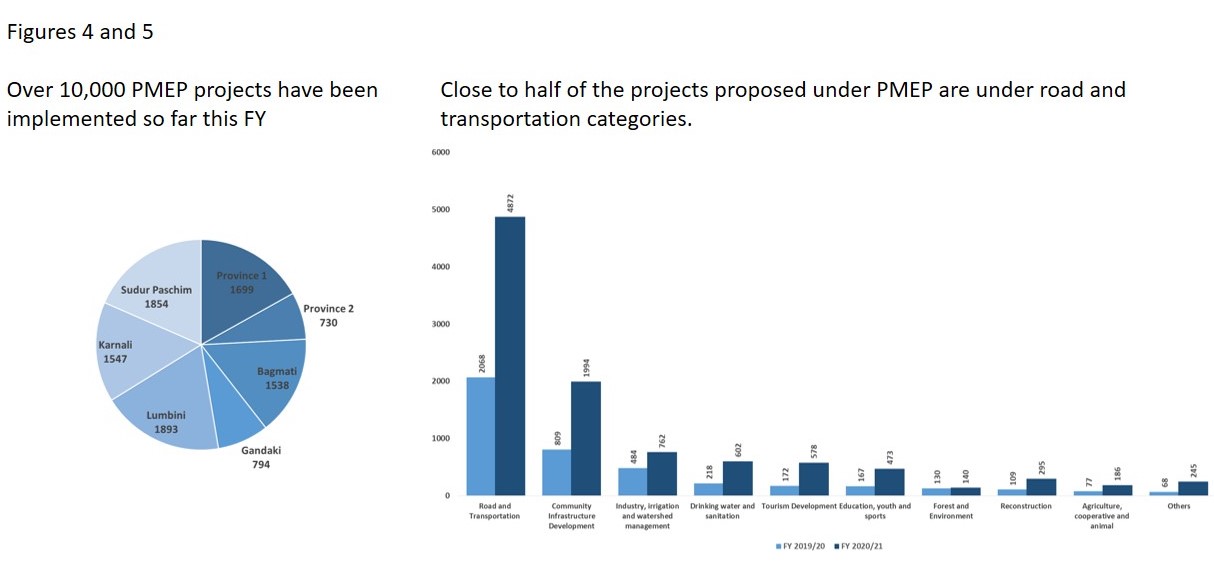

So far in 2020-2021, over 10,000 PMEP projects have been implemented across the country, up from 4,302 last year (see Figures 4 and 5). About half of the projects are on roads and transportation. Applicants who are shortlisted are asked to form a group and coordinate with the ward on a pre-approved project they want to work on.

One challenge to PMEP implementation is that the allocated budget can be spent only on wages, and not on equipment. “If it is a road project, for example, they need cement, shovels and safety gear. Who will provide that?” questions Bishaksen Dhakal, Chief Administrative Officer at Sindhuli’s Kalamai municipality.

He adds: “In an ideal scenario, the local government’s budget would be used to cover material and equipment costs, but there is not much enthusiasm about this at the local leadership level.”

The PMEP budget is also released much later than the fiscal allotment, leading to unwillingness on part of local governments to readjust their plans.

Dhakal notes that there must be increased coordination between the federal and local governments so the latter sets aside a budget for PMEP projects equipment and material in advance or the guideline must be updated to allow for non-wage related expenditure.

In Karnali Province, a parallel Chief Minister’s Employment Program (CMEP) has relieved pressure on municipalities. “CMEP nicely complements PMEP and has provided relief on various fronts. Salaries of both programs are the same so the jobseekers unable to benefit from PMEP can get work through this program. Furthermore, there is more leeway with the CMEP because the 40 per cent of the budget can be used for the purchase of equipment and material,” says Resham Bahadur Budha, Chief Administrative Officer of Narayan Municipality in Dailekh.

In Narayan municipality, for example, CMEP is expected to employ 1,000 individuals for 50 days in 22 projects. Of the 3,000 people registered for PMEP, less than 500 received some form of work.

For a more lasting impact, local leaders stress on the need to equip PMEP beneficiaries with marketable skills and experience. “If the scheme had an element of graduation, beneficiaries could eventually wean off the program. Currently, they benefit from the program doing labor work for the number of days they are allocated, which is irregular and uncertain. Support like training would make them more employable,” says Mayor Ganesh KC.

He also emphasises on the need to further strengthen the Employment Service Centers, especially to coordinate with the private sector who are the real job creators. Appeals to local employers and associations to make use of local labor, including those registered as unemployed under PMEP, have not yielded results yet.

“If there is a need for a plumber, it would be good to rely on a roster of plumbers at ESC to hire from. As it is now, PMEP is not designed for skilled but unemployed workers who have higher reservation wages and skills so we need to think beyond PMEP,” he says.

Beyond lapses in current infrastructure such as the capacity of the ESC and the available MIS system, KC notes that relying on ESCs for job placements also demands a mindset change: “As jobseekers and employers, we are habituated to relying on personal referrals and networks so such new practices will take time to adapt to.”

Suman Ghimire at the Labour Ministry shares that it is working to strengthen ESC to play a stronger coordination and referral role and has set aside a budget to train over 59,000 PMEP beneficiaries for next fiscal year, but makes it clear that the scheme is not for the skilled workers.

“We need to understand that PMEP is targeted to the poorest who are struggling to make ends meet. For the unemployed who are skilled and educated such as returnee migrants, there are self- and wage-employment programs run by other line agencies. We have prioritized strengthening the capacity of ESCs to play a strong coordination and referral role because the various programs are scattered and potential beneficiaries may not necessarily be aware of these schemes,” he says.

Those we spoke to, from Mayors to ECs, express the enormous potential of PMEP to help the poorest of the poor. The jobs are in their proximity and for many, including women, it is a convenient way to boost household income especially during agricultural lean seasons.

With the pandemic, both domestic and foreign employment are on shaky grounds. This further increases the demand for programs like PMEP to provide temporary respite to individuals so they can better cope with the widespread economic shock.

According to the World Bank Covid-19 monitoring survey, two out of five economically active workers reported incidence of job loss or prolonged work absence. Internal migrants are returning back to their villages en masse. Seasonal migrant workers from India are reeling under the second wave. Emigration to third countries beyond India is picking up, but slowly and unevenly. The macro-picture of remittance may have defied predictions so far but many have lost their overseas jobs, and with it an important income source that has served as the only reliable safety net. Disbursement of the government’s soft loan programs to encourage self-employment initiatives have shown modest improvement but are far from the desired targets. (See Figure 6)

The story of Hari whose journey we have covered over the months shows how helpless migrants are in the face of the crisis. In May, Hari made an arduous journey back to Banke from Ahmedabad despite the risks of traveling.

“It is better to die in my own country,” he told us then, as he trudged to the Nepal border on India’s Shramik train. Five months later, he went back to Ahmedabad to work with the same employer, a hotel, despite the COVID-19 crisis in India. On the phone in December, he asked us rhetorically: “How will my family survive if I don’t migrate?”

A few weeks back, as the crisis gripped India, he again escaped to Nepal, wary that things were quickly spiraling out of control and wanting to avoid the border and quarantine complications he faced the first time back. The back and forth and uncertainty has worn him down.

“I am lucky to be alive. Two of my Nepali friends in Gujarat, a few hours from where I worked, died of Covid-19. It could have very well been me. At least I managed to escape and am alive and safe,” he says.

But this recognition does not take away the financial stress back home as his family is already struggling to make ends meet and as a sole bread winner, his job prospects are dim. His is not an isolated story, of families in dire need of temporary safety nets to fall back on till the situation allows them to get back on their feet.

Now more than ever, social protection programs are needed to provide a lifeline to the poorest. With the second wave, local governments are once again overwhelmed with flooded hospitals, returnee migrant management, and shortages of all kinds. As pointed out in the 2019-20 PMEP report, in the context of the pandemic, the PMEP needs to be adapted to address local needs to help fight the crisis including building of temporary structures for isolation, contact tracing, sanitation drives, social awareness programs under Covid-19 safety protocols.

The second wave and the quickly unfolding crisis further underscores the need to leverage this program for such activities. Given the current situation, the immediate need of the hour is also to cast the safety net wider by providing traditional emergency cash- or food-based assistance to help the poorest cope with food insecurity so families who have lost their livelihoods can ride out the crisis.

Over the last three years PMEP has had a checkered reputation because of allegations of wasteful spending, unproductive work and improper targeting of the unemployed.

“We are best placed to give critical feedback on implementation challenges,” says one EC. “It would be helpful if they came to monitor our work from the center, to understand the ground realities. As ECs, for example, we are still under-resourced as we do not have allowances for transportation to travel to the wards that we are in charge of, some of which are quite distant from where we are based. Sometimes, it is simple challenges and small kinks, if sorted, could go a long way.”

The federal government has been receptive to some other feedback from local governments and ECs, especially the current daily wage of Rs517 being too low by local standards, and are considering to readjust it for next fiscal year. This, however, is a tricky task.

On one hand, the wages need to be high enough to make a meaningful difference to the poor. But on the other, low-wage setting aids with proper targeting by ensuring the intended beneficiaries i.e., the poorest self-select into the program and those who are not poor or have alternate income sources are not attracted to PMEP.

To be fair, at just its third year, PMEP is still at its nascent stages and it will take a while for this massive undertaking to take off smoothly, further complicated by the pandemic.

Comparator programs like India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), for example, celebrated its 15 years this year. In 2020-21, one hundred ten million jobseekers benefited from MNREGS, a 39% jump from the previous year, proving to be critical for distressed workers during the pandemic despite implementation challenges such as payment delays and job rationing.

But as promised in the last budget, the expectation from the Nepal government’s flagship employment program during this unprecedented time was for swift and bold action, both because of and in spite of Covid-19.