FIFA a chance to improve welfare of Nepali workers in Qatar

In 1998, a New York Times report about a 10-year old from Sialkot in Pakistan, who stitched footballs with her mother for a pittance, led to an international campaign against child labour.

Two decades later, Nepali men are making stadiums in Qatar for the FIFA World Cup where balls manufactured in Sialkot will be kicked in 2022.

Recent media reports of deaths of 6,500 workers from five Asian countries, including Nepal, in Qatar in the past 10 years got similar global coverage.

Fatalities directly linked to building eight stadiums reportedly stands at 37. Some argue that all deaths in Qatar are related to FIFA, as the hiring in the last decade was for this mammoth stadium-building. Others find this conclusion misleading.

The reportage from Sialkot 20 years ago showed that linking child labour with football can generate global outrage and put pressure on brands like Nike and Adidas to reform. Now, FIFA has elevated awareness of migrant rights issues globally in sectors like construction. This has created space for strategic advocacy to push for long overdue reforms in Qatar and to a lesser extent, recently with Malaysian medical glove manufacturing in which Nepalis are also involved.

With the global attention, it was anticipated that FIFA would dramatically transform working conditions for migrant labour in Qatar. It did not. But there have been significant reforms.

The Qatar Government has collaborated with agencies like the International Labour Organisation (ILO) to push for significant reforms, some of which are the firsts in the Gulf and the implementation of which could send ripples across the region.

The minimum wage has been revised, and workers are now allowed to change employers without permission, essentially dismantling the notorious kafala system. Ray Jureidini, a professor at the Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar says references to kafeel and kafala have been removed from the labour law, even though this has not completely translated to practice yet because a sponsorship system is still functioning.

The reforms have also faced resistance from employers, and the law was sent for review to the Shura council which has recommended diluting its provisions. This includes not allowing job-switch during a contract, capping the number of job changes allowed or the share that can change jobs per company. This risks undoing the much anticipated reforms.

However, Kareem Baksh Miya, a Nepali living in Qatar, says the impact of the reforms are tangible: “We need to recognise the emphasis on labour reforms, improvement in monitoring, wage payment system, appointment of medical workers and safety officers.”

Not everyone shares his optimism in Qatar. The efforts are viewed as too-little-too-late, and disproportionately applied with migrant workers falling between the cracks.

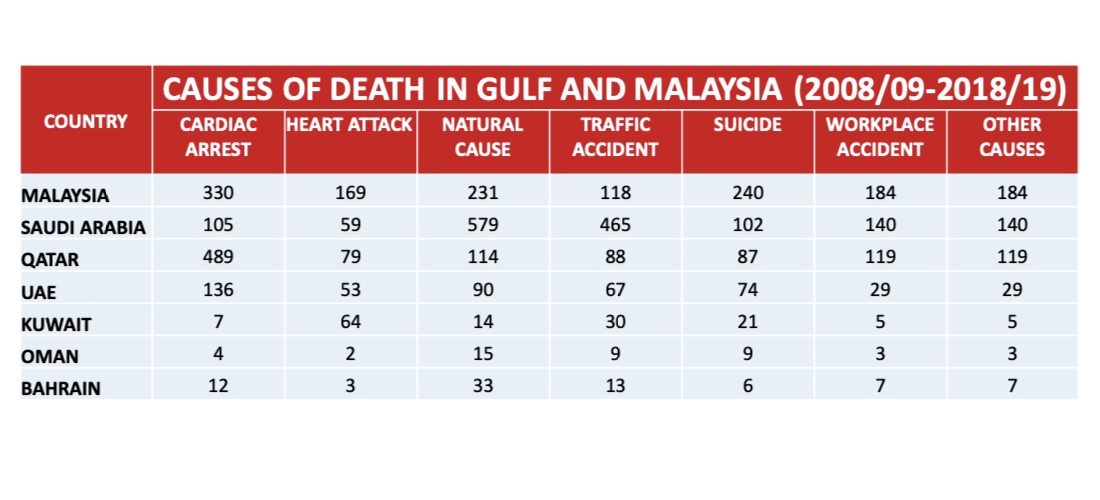

The lack of proper investigations into migrant deaths has also been criticised. One major hurdle is that there is no publicly available data on fatalities. Statistics are also not disaggregated by age and nature of work, which limits a clear understanding of the issue.

A Qatar-based Nepali doctor stresses the need for data not just on migrants in Qatar but the need to expand the understanding of how these numbers compare to similar work in other countries.

“The authorities should consider forming teams of medical and public health professionals to really dive into the issue which is long overdue,” he says.

There is also a lack of investigation into the real cause of the deaths. “सुत्दा सुत्दै मर्यो,” has become a colloquial phrase among migrants in the Gulf and Malaysia where many workers die in their sleep.

“In Islam, autopsies are conducted only if it is absolutely necessary like in criminal cases,” explains Prof Ray Jureidini, who adds that the Qatar government should allow post-mortem examinations in case of sudden deaths and a proper, comprehensive epidemiological study is urgently needed.

“Classification of cause of death as cardiac arrest is itself problematic because everyone’s heart stops when they die,” Jureidini says. “In this day and age, a diagnosis of unexplained sudden cardiac arrest is not really acceptable, particularly for the families of the deceased."

Heat stroke is thought to be an underlying cause of deaths. A paper in Cardiology Journal found strong correlation between heat stress and young workers dying of cardiovascular problems in summer. It estimates that 200 of the 571 cardiovascular deaths between 2009 and 2017 could have been prevented with effective heat protection measures.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has long been pushing for Qatar to move towards real-time weather conditions to decide outdoor work hours, instead of pre-defining them.

However, Jureidini says the deaths cannot be attributed to heat alone, citing figures that show that of the 705 Nepali workers who died between 2011-2014, 57.5% occurred in April-September when temperature is the highest. Of those classified as cardiac arrests, 61.2% died in the six summer months.

“There is more than heat causing the deaths that needs to be further investigated. Without reliable data and with no post-mortem examinations, we are just speculating. Everybody is just guessing,” he says. The real task of an inquiry is to explain why some workers are dying and others are not, under the same conditions.

While a more scientific and systematic approach involving the medical community is important, he also underlines the need for pre-departure health screening. He shared the example of medical screening for Gurkha enlistment who undergo mandatory ECG and ultrasound to identify risk of sudden cardiac death during heavy exercise.

Outgoing migrant workers now go through basic pre-departure tests like x-ray, medical history, blood pressure. The adequacy of these tests need to be ascertained and follow-up health checkups at the destination are needed.

“There is a need to increase awareness levels among migrants. After a long day’s work in blazing heat, for example, if migrants sleep in cold air conditioned rooms, it can be detrimental. Proper nutrition, staying hydrated and knowing when to ask for help is also needed,” says Kareem Miya.

Qatar-based physicians interviewed for this article also underline the need for awareness programs in Qatar itself on issues like mental health, dehydration, temperature control, accident prevention and Covid-19.

Malpractice in recruitment including costs also take a toll on both the mental and physical health of migrants who exert themselves to recoup costs.

A worker from Sarlahi we contacted in Qatar had to migrate because his parents were Rs500,000 in debt. But he himself had to take out a Rs150,000 loan to pay recruiters. It will take him three years to pay it all off.

He does not care much about the FIFA World Cup, but is worried he may lose his job as the games approach. “I have transitioned to maintenance work now, but my company is very small and may not win contracts as we approach the game as preference will be given to the bigger, better known firms,” he adds.

But there are ‘FIFA stadium alumni’ like Padam who was featured in the documentary Worker’s Cup who is passionate about the World Cup. He left Qatar six years ago and is now in the UAE.

“I played in the Khalifa International stadium and still watch the documentary,” says Padam, who himself took a year just to pay back the loan he took to pay recruiters.

The Nepal Government needs to be more proactive and take advantage of the room to use labour diplomacy or ‘FIFA diplomacy’. Existing platforms like the Colombo Process and the presence of embassies in destination countries need to be leveraged to push for more data transparency and investigations of worker deaths.

As FIFA draws close, Prof Ray Jureidini predicts that the pressure on Qatar will further increase. But how the public outrage translates to meaningful action on worker welfare will be what really matters.