India’s border trains that connected Nepal

Once upon a time, Nepalis had to travel through India by railway to reach another part of NepalIndia has the British to thank for its extensive nationwide rail network. China is now foremost in the world for fast trains. In between, Nepal is stuck in the slow track, and has let its historical railway lines in the Tarai rust away.

An interesting subject for research by students of history can reveal how railway lines linking Nepal to British India shaped the political economy and social life of the day.

The British built tracks to log Nepal’s Tarai forests for teak sleepers needed for new railway lines across India. But the train tracks also opened up Nepal to the world. And to itself.

Nepal helped build India’s rail network with raw material, but only built two short lines of its own. Railways were introduced to India in 1886 by the British, not long after the invention of the steam locomotive. The rail network spread rapidly till 1914, a time when the demand for railway sleepers soared and the Tarai forests were mined for logs.

The border town of Raxaul inaugurated its railway station on 1 March 1899. Once Raxaul was connected, it became easier for people from Kathmandu travelling to various parts of India, or even to other parts of Nepal, to take trains. India’s railways therefore also connected Nepal.

When the Rana regime finally built train tracks, they were limited to the Raxaul-Birganj-Amlekhganj and Jayanagar-Janakpur-Bijulpura tracks for goods and passengers. Much later, train tracks were also built to ferry stones and logs during the construction of the Kosi Barrage in 1958-1962.

Read also: Nepal Railways Janakpur test drive

It was only after the completion of the East-West Highway in the 1980s that the reliance of Nepalis on Indian trains was reduced. Until as recently as a decade ago, there was no alternative to taking an Indian train to get from one Tarai district to a neighbouring one, or even to travel within a district in Nepal.

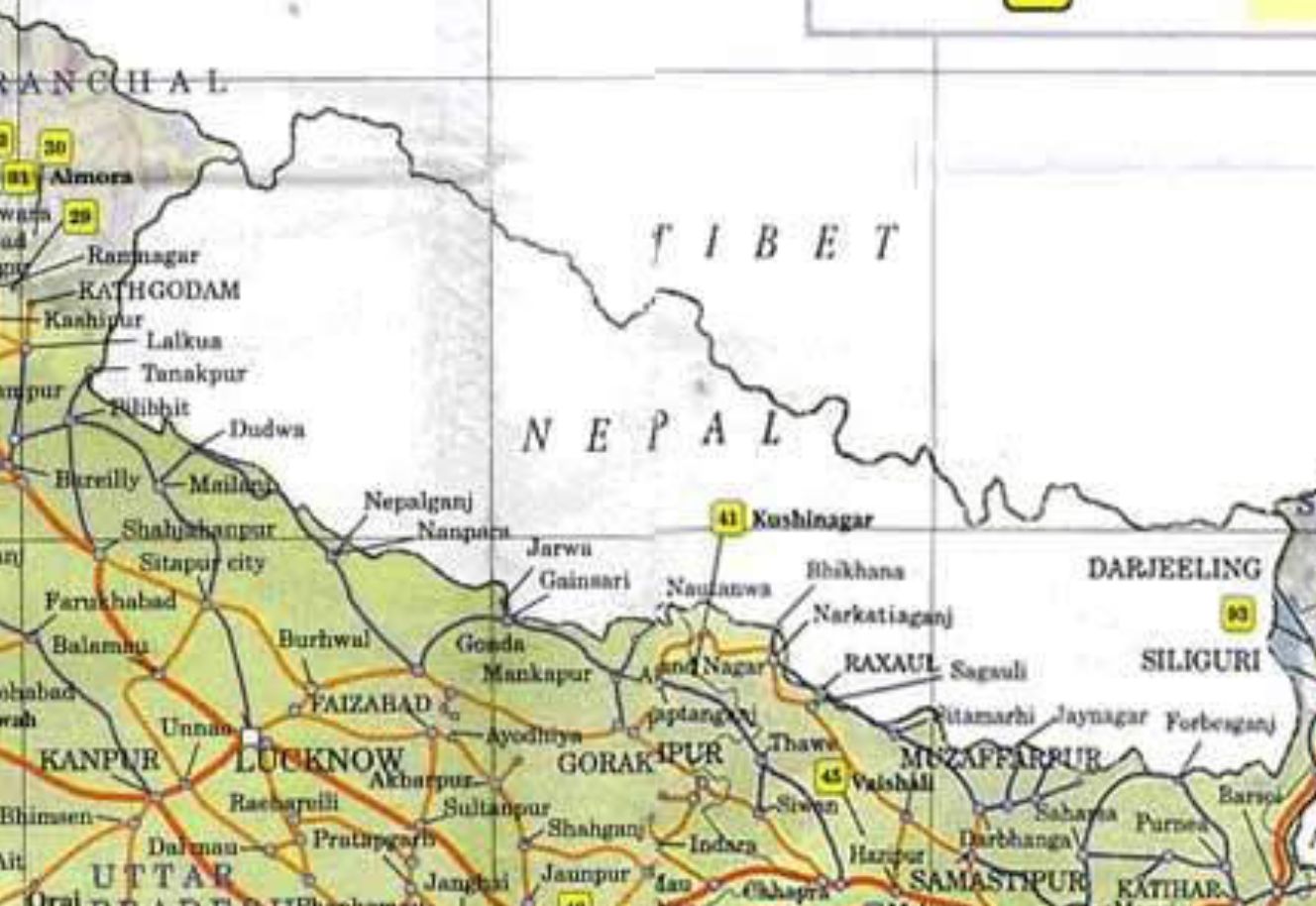

Indian narrow gauge train stations near the border became everyday names in Nepali conversation because of their importance to domestic connectivity: Galgaliya, Jogbani, Katihar, Nirmali, Kunaili, Bairgania, Dheng, Ghodasahan, Thutibari, Nautanwa, Badhani, Gorakhpur, Sunauli, Gonda, Bharaich, Murtiya, Tiukunia, Gauriphanta...

Even today, as feeder roads join Tarai towns, some of these stations are still used extensively by Nepalis. One of them is the border village of Thori on the west of Parsa district.

People in Thori used to take an Indian railway train at the Bhikhna-Thori to travel to the district capital of Birganj via Raxaul. In fact, the station catered almost exclusively to passengers from Nepal, and once the road joined Thori with Birganj, Bhikhna-Thori railway station fell into ruin.

The Bhikhna-Thori station was built in 1906, and British royalty and the Governor General from Calcutta used to take it for hunting expeditions organised by Nepal’s Rana rulers in their honour.

Similar rail links joining the Nepal border to the Indian rail network were built in Gauriphanta to connect Dhangadi (1914) and Kanchanpur to Tanakpur (1912). Gauriphanta was closed because Dudhwa became an Indian national park, and Tanakpur was converted to broad gauge.

The importance of Nepali travelers to Indian railways can be gleaned from the name of Rupediya station, which is still officially called ‘Nepalganj Road’ Station.

Similarly, there is a ‘Janakpur Road’ Station along the Samastipur-Narkatiaganj line in Bihar state, even though the name of the town itself is Pupari. The reason for this could be so Indian pilgrims headed to Janakpur would know where to get off.

The crossborder railway was essential not just for passengers but also Nepal government administrative work. Not only were the mountains roadless, but even Tarai towns were not connected by motorable roads.

After Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal became the first to climb an 8,000m peak when they summited Annapurna in 1950, they walked from Base Camp for weeks to the Indian border at Sunauli, took the Indian trail to Raxaul, connected to the Amlekhganj train and then trekked up the mountains to Kathmandu to meet Prime Minister Mohan Shumsher Rana.

Herzog made the journey in the heat of the Indian summer. His frostbitten toes and fingers were turning gangrenous and had to be amputated in the train.

Lack of connectivity in Nepal and the presence of Indian train stations at the border meant that Nepal’s socio-economic life and political orientation was to the south. It was only after connectivity within Nepal improved starting in the 1970s that the periphery could go directly to Kathmandu without routing via India.

This change had a profound impact on education, health, trade, and even in the mindset of Nepalis. In his book, Regionalism and National Unity in Nepal, American scholar Frederick H Gaige says that the basis of the early industrialisation of the Nepal Tarai towns was that they were connected to the Indian rail network.

Read also: Putting Nepal on the right track, Arnico Pandey

Gaige argues that the expansion of its railway network to the Nepal border was also linked to India’s own economic growth trajectory northwards in the 19th century as markets for agriculture surplus from the Nepal Tarai. Traders from the Madhesi community prospered because of the presence of these stations, and some invested their profits in property there. It was a sign of great prestige for traders from Nepal to own assets in Indian railheads.

India’s railways even influenced Nepal’s political awakening, starting with the 1950 anti-Rana movement. Being able to coordinate protests across Nepal was only possible because of the ease of travel by rail via India. Even during the 1980 referendum, anti-Panchayat reformists found refuge in rail stations across the border.

Finally, there was also the social impact. Connecting various parts of Nepal, even the mountain districts, with each other made it possible for families from eastern Nepal to marry their children to those from the west – something that would have been difficult, if not impossible, had they not been able to travel on Indian trains.

Nepal was a closed kingdom in those days, but Indian trains also opened the eyes of Nepalis to the world outside: Calcutta, Banaras, Bombay and beyond.

Read also: India-China rail race, Shristi Karki

writer