Nepal's far-sighted eye care

Despite a decade long conflict, the absence of local government for 20 years, instability and bad governance, Nepal has taken dramatic strides in improving the health of its citizens. And it is in eye care that the achievement has been most impressive.

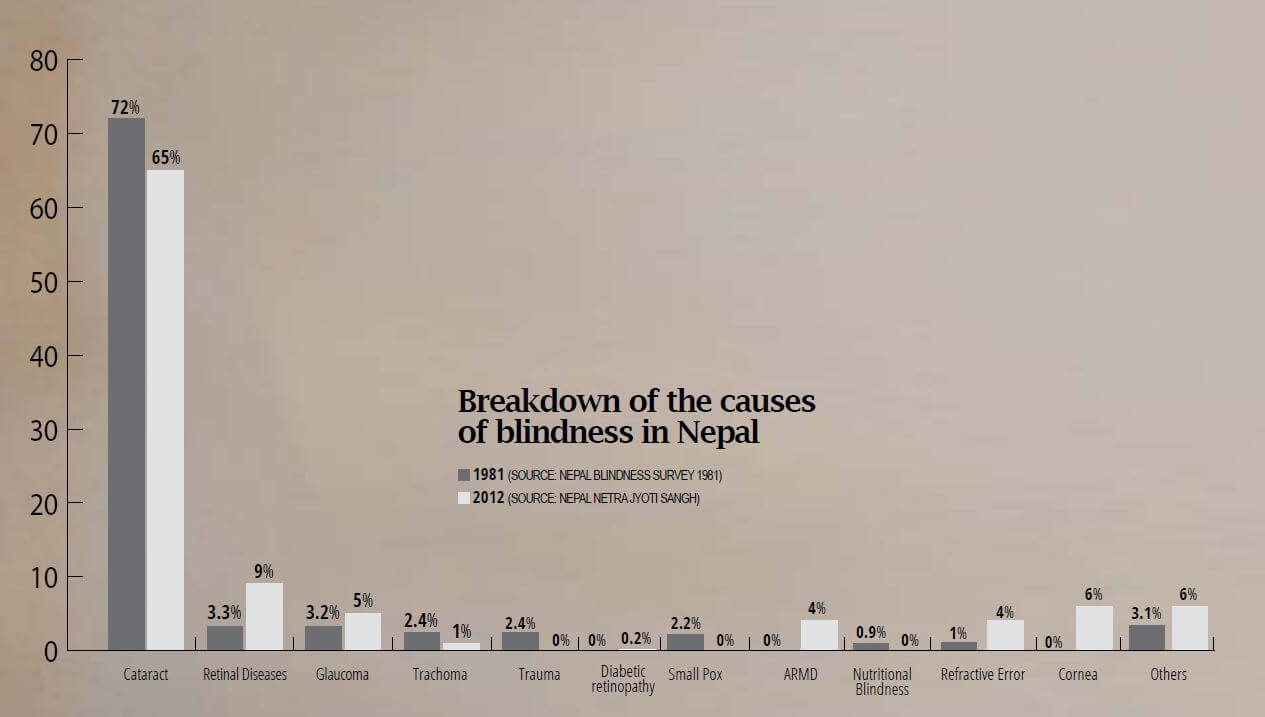

Thirty years ago, the Nepal Blindness Survey showed that 0.8% of the population was blind. Nepal’s population then was 15 million, which means 118,000 people were blind. Cataracts was the cause in 72% of the cases, and trachoma, a bacterial infection of the eye, was the second leading cause of blindness. Poor eye-sight and blindness due to Vitamin A were also prevalent. Most of these were preventable or curable. Women were found to be 1.35 times more likely to get cataracts because of the detailed nature of their work, and injuries stemming from household work and farming.

Today, the prevalence of blindness has decreased to 0.3% out of a population of 29 million, which means only 87,000 are visually impaired. But most of them are blind still because of cataracts. Last year Nepal became the first country in South Asia to eliminate trachoma. Cataracts and other preventable cases can now be treated much earlier with modern surgery.

“The quality of community cataract surgery here is one of the best among developing countries and people are coming forward for treatment because they trust us,” said Sanduk Ruit, Nepal’s world-renowned eye doctor who pioneered small incision cataract surgery. (See below)

But modern lifestyles and changing dietary habits have brought new dangers: diabetic retinopathy is on the rise, so is glaucoma. An ageing population also means cataract is still common, as is macular degeneration among elderly Nepalis.

The most challenging ailment, however, is visual impairment due to refractive error which is increasing alarmingly among children, and at a much higher rate in urban areas. A 2008 study found that one in five school-going children in Kathmandu were short sighted and need to wear glasses. In remote rural areas, many do not even know they need spectacles or cannot afford them.

Ruit’s team at Tilganga and the group Nepal Netra Jyoti Sangh are now trying to test and treat the eye-sight of school children district-by-district. Free spectacles are provided, and complicated cases are referred to hospitals.

“Our goal is to reach all school-going children in Nepal within five years,” said Sailesh Mishra of Netra Jyoti. “This needs regular monitoring and follow-up if children are using glasses or not, and we need to educate people about eye diseases.”

While there has not been a study in Nepal to directly link the increased incidence of visual impairment with the use of mobile phones, computers and reading, research in other countries have shown a correlation.

Nepali eye specialists and institutions have not just addressed blindness in Nepal, but have been world leaders in innovative interventions. Sanduk Ruit’s Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology has been exporting intraocular lens for cataract surgery at $5 apiece since 1995. Elsewhere in the world it costs $200. Tilganga is now equipped to also perform retinal transplant.

Eye hospitals in Lahan, Hetauda and Kathmandu now treat not just patients from Nepal, but also provide affordable cataract and other eye operations for patients from India, and even Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

Read also: Two Decades of Vision, Skye Macparland

Tilganga has is an international centre of excellence for ophthalmology training, and its surgeons have been conducting camps in Bhutan, Mongolia, North Korea, Ethiopia and Kenya. Much of this is credited to non-government initiatives by the likes of Sanduk Ruit and pioneer activist Ram Prasad Pokhrel.

“One of our most important achievements was to provide eye care outside the government, creating high quality community hospitals at the grassroots that run on the social entrepreneurship model with highly motivated professional staff,” explained Ruit, whose community eye centres and hospitals are autonomous and self-sustaining.

But with its Vision 2020 goal to eliminate avoidable blindness now only a year away, Nepal needs to develop more specialists and infrastructure. Some experts say the non-profits have done all they can, it is now time for the government to step in for the last push.

“Nepal is far ahead of others in the region in term of eye care, we have reduced blindness, have sound modern surgical technology that has been recognised internationally,” said Hukum Pokhrel of Netra Jyoti. “It is now time the government included eye care into a more equitable health package that is sustainable into the future.”

The Visionary Sanduk Ruit

New biography of the Nepali eye surgeon who overcame

all odds to give the gift of sight to the world

It was on the death bed of his young sister that Sanduk Ruit vowed to grow up to be a doctor so others like her did not have to die needlessly. Later, at a surgical camp he found his true calling after observing the magic of restored eyesight.

There were many such instances that turned this boy from a family of salt traders in Olanchungola on the Tibet border into a world-renowned surgeon. Reading Ruit’s new biography, The Barefoot Surgeon, we find that it was sheer determination, hard work and perseverance that helped him overcome many obstacles on the way to rising from a remote village in Nepal to become an internationally acclaimed doctor.

“I want this book to create awareness about how we alleviated blindness in Nepal, and how this experience can be fine-tuned and replicated in other parts of the world,” Ruit said in an interview, ahead of the launch of the soon to be released book.

Australian journalist Ali Gripper recounts how his mother named Sanduk (sky dragon), and the family was so poor Ruit lost siblings to preventable infections like diarrhoea and tuberculosis. At boarding school in Darjeeling the young Ruit was bullied mercilessly, he spent hours with lab animals as a diligent student pulling all-nighters at King George’s Medical University in Lucknow, then operated on rhesus eyes in ophthalmology class at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi.

Much of the book describes Ruit’s years as a junior eye surgeon trying to shake up the government health system in Nepal to introduce intraocular cataract surgery. He is rebuffed by seniors who see his motivation as a threat. Gripper follows Ruit’s transformation into a young man with a vision to rid the world of avoidable blindness.

Along the way, Ruit is mentored by famous Australian eye surgeon Fred Hollows, and much later American climber-surgeon Geoffrey Tabin becomes a protégé. Both individuals play a significant part in expanding Ruit’s transformative work, and leave a profound impact on the doctor.

Ruit is known for pioneering the technique of small incision low-cost cataract surgery which he has used to restore the sight of more than 120,000 people so far in Nepal, China, North Korea, Ethiopia and other countries. He has won many accolades including the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2006, and last year one of India’s highest civilian honours, the Padma Shri.

As he interacts with patients in Kathmandu, he shows extraordinary kindness and humility for a doctor so famous. Ruit tells Gripper that he learned early in his career that giving back eyesight to people meant giving them back their life. Ruit’s life is not without personal tragedies, and the book is full of heartfelt moments. But it is as much about progress in eye care in Nepal as it is about Ruit himself.

“Curing blindness is Nepal’s great success story,” said Ruit, who established the Tilganga Institute of Opthalmology in Kathmandu in 1994. At that time the prevalence of blindness in Nepal was 0.8%, with cataract the major cause. Today, blindness is down to 0.3%, despite the population having doubled, and Ruit is operating much earlier with improved surgery on contracts.

The world-class eye centre is also a training ground for young surgeons from around the world. Tilganga runs on the social entrepreneurship model with a sliding scale payment system where those who can afford treatment pay more than the less privileged.

“Instead of investing time and money on mega projects, we should focus on developing small, self-sustaining grassroot independent community hospitals with qualified staff, and that is the most important thing we have achieved in eye care in Nepal,” said Ruit, who has opened eye centres in all 77 districts, with community eye hospitals based on the Tilgaganga model in Hetauda, Biratnagar, Dhangadi, Nepalganj and Lumbini.

The Barefoot Surgeon is being translated into Nepali by FinePrint, but it is not the first book about Ruit. Second Suns by David Oliver Relin, who also wrote Three Cups of Tea, was about Ruit and Tabin’s quest to restore sight to the world’s poorest. But following an allegation of plagiarism in an earlier work, Relin committed suicide in 2013 right after handing over the manuscript of the Second Suns.

Read also: Helping the poor to see, Kunda Dixit

For the new book, Gripper followed Ruit’s surgery team for more than three years in India, Bhutan and Burma. In Nepal she joined Ruit’s eye camps in Trisuli, Mustang, Hetauda and Solu Khumbu to see people seeing again. She noticed that Ruit preferred to work barefoot ‘allowing him complete control of the pedal under the table that pulls focus on his microscope’.

The book recounts Ruit’s vision for Tilganga, the rapport he shares with Bhutan’s Queen grandmother, the eye camp in North Korea where minders followed their every move, his meeting with the Dalai Lama, the challenges in manufacturing low-cost intraocular lens in Kathmandu, and a treacherous journey to Mustang for a field camp.

There will be tears of joy and of sadness, there will be elation and wonder as you turn the pages of The Barefoot Surgeon. This is a moving portrayal of a great Nepali whose work has transcended borders to transform many, many lives.

Sonia Awale

The Barefoot Surgeon: Inspirational story of Dr Sanduk Ruit, the eye surgeon giving sight and hope to the world's poor

By Ali Gripper

Allen & Unwin, 2018

305 pages

AUD $32.99

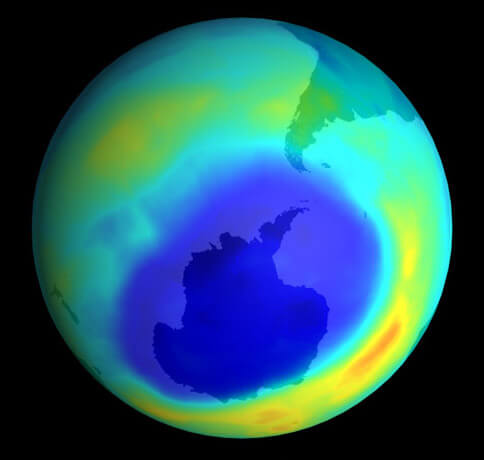

Ozone and Eyes

The ozone layer in the outer atmosphere filters out harmful ultra-violet rays of the sun from reaching the Earth’s surface. There has been a steady depletion of this, especially over the Southern Hemisphere, due to chemicals called CFCs used as a refrigerants. This has caused a rise in the incidence of skin cancer, but also of eye disorders. People living southern Argentina, Australia and New Zealand have been known to suffer more cataracts because of the solar UV-B radiation.

A 2005 study carried out by the American Journal of Epidemiology found out that ozone depletion would result in a 20% rise in the number of cataract cases by 2050. Ultraviolet rays is also responsible for the onset of cataract at an earlier age. Not just people in the southern hemisphere, but those living in high altitude areas like the Tibetan Plateau and Nepal also become more susceptible to cataracts due to ozone thinning.

Apart from cataract, UV radiation can also cause photokeratitis (inflammation of the cornea), eye cancer, conjunctivitis, pterygium, conjuctivitis, acute solar retinopathy, and degeneration of the macula. Long term exposure to the harmful rays can cause permanent damage to cornea, lens and retina.

As a result of the 1985 Montreal Protocol to phase out CFCs, the ozone hole over Antarctica has started to shrink, but exposure to UV B radiation will be seen till the end of the century. HFCs that replaced CFCs in refrigerators and air conditioners are very potent greenhouse gases that contribute to the global warming.

Doctors say, minimising the time spent outdoors especially in the southern hemisphere and at high altitude is a useful precaution.

writer

Sonia Awale is the Editor of Nepali Times where she also serves as the health, science and environment correspondent. She has extensively covered the climate crisis, disaster preparedness, development and public health -- looking at their political and economic interlinkages. Sonia is a graduate of public health, and has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Hong Kong.