North Indian heat wave hits Nepal

This spring, northern India saw the hottest March since records started being kept 120 years ago, and this week people in the Indo-Gangetic plains are bracing themselves for maximum temperature to hit 50°C. All this hot air is also affecting next-door Nepal.

After sweltering through record March heat, Kathmandu’s average temperature this week was at a 53-year record. Dharan registered 35.7°C in mid-March, another record. People in Nepal’s Tarai are used to heat waves, but not in March and April.

All this makes Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2020 climate fiction The Ministry for the Future prophetic. It starts with a town in northern India as it faces a deadly heat wave that kills most of its 200,000 inhabitants in a week. The facts of climate change induced heat stress are imitating fiction, and a dystopian narrative is becoming our new reality.

“Heat, temperature and moisture combined will be the killers in South Asia, and if there is anything that will genuinely force people to respond to the climate crisis it is frequent heat waves, because unlike other episodic extreme events it is widespread and will impact everybody,” Ajaya Dixit of the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition (ISET) Nepal told us from New Delhi where the maximum temperature was 44°C on Tuesday.

A recent study from 2000-2019 found that over 5 million people around the world died each year in that time due to extreme temperatures, with some 2.6 million in Asia – with most of the fatalities in South Asia. Heatwaves in 2010 killed more than 1,300 people from dehydration and stroke in Ahmedabad alone. Another severe heatwave in June 2015 during which the mercury hit 49.4°C caused the deaths of 2,500 people in northern India and 2,000 people across the border in Pakistan.

Another heatwave in India and Pakistan in 2019 was the hottest and longest since the British started keeping temperature records, with the maximum at 50.8°C in Rajasthan. A similar but slightly less intensive heatwave in Europe in 2003 killed between 35,000-70,000 people.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) Climate and Health country profile for Nepal predicts that under a high carbon emission scenario, heat-related deaths in people above 65 years are projected to increase to about 53 deaths per 100,000 by 2080 compared to the estimated baseline of approximately 4 deaths per 100,000 annually.

While dry heat is still bearable because the body cools with perspiration, it is humid heat that is more lethal. And climate change is not just making the world hotter, but also wetter. For every 1°C rise in temperature, there is 7% more moisture in the atmosphere.

This is called ‘wet-bulb temperature’ that measures both ambient air temperature and humidity level to determine how hot it actually feels. For example, if it is 30°C with high humidity, it will feel much warmer.

A wet-bulb temperature of 35°C is considered the maximum limit of heat and humidity that humans can handle. Beyond that, the body can no longer effectively cool itself via perspiration. A couple of hours of exposure to this without artificial cooling will mean that people will start dying of heatstroke and dehydration, with children and the elderly being the most at risk.

“The climate crisis in the Himalaya is the water crisis. Heat stress is manageable as long as there is access to water, but that is not the case for the poorest in the Tarai,” says climate scientist Binod Pokharel. “Luckily, this week’s heat wave is mostly dry heat with lower humidity.”

The rain that is forecast for Nepal from Thursday will cool things down, but it will also increase the humidity.

The other factor making heatwaves more intense are densely populated cities of vehicle exhaust, concrete and asphalt which form what are called ‘urban heat islands’. Ironically, the air conditioners city dwellers use to cool themselves indoors, is making it hotter still outside.

There is a significant temperature gradient between the outskirts and Kathmandu’s city centre even in winter, which means the Valley does not have its characteristic winter fog anymore. On any given day, there is a temperature difference of 1.5°C between Chobhar and Teku, even though the two places are only 3km apart.

As more and more open spaces are built over and the greenery disappears, Kathmandu’s ‘heat bubble’ is going to get bigger. Warns Dixit: “The fast pace of urbanisation in South Asia is a serious threat and we are a witness to an unfolding disaster. Business as usual means higher cost of response, both financially and institutionally.”

He says the only solution is to start designing climate smart cities that restore open spaces and building houses with insulating material and use or block sunlight, reducing the need for energy-intensive heating or cooling.

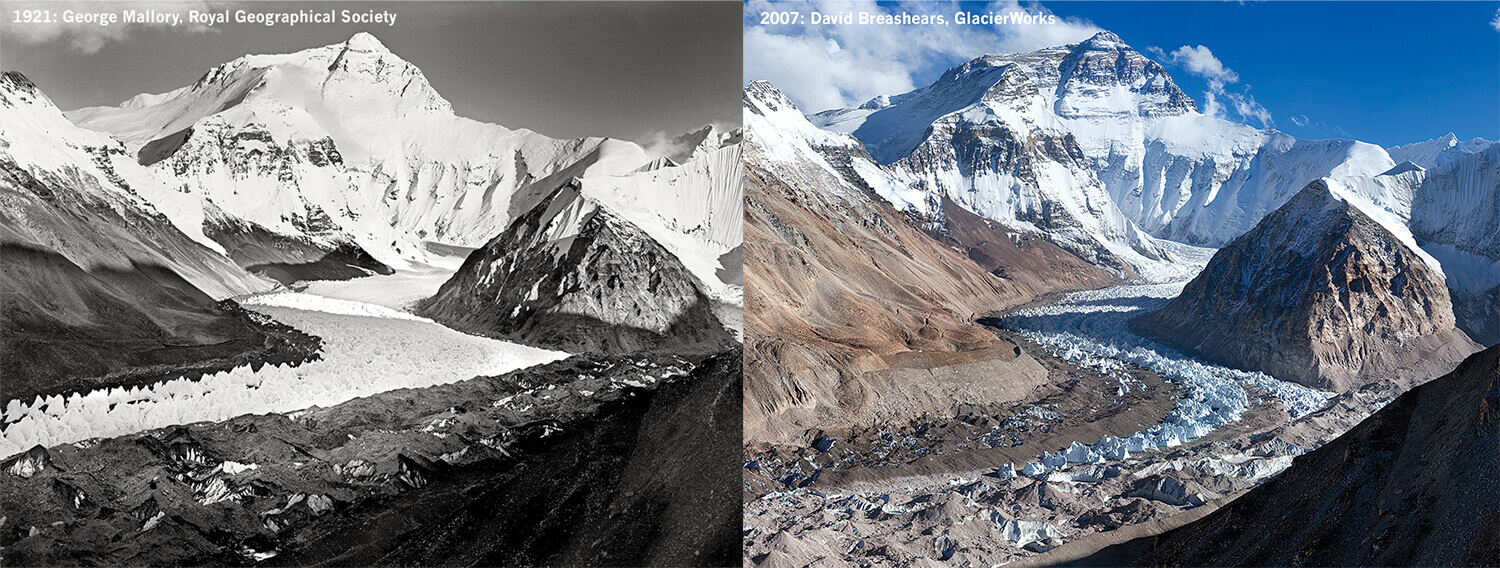

The impact of increased heat in the Tarai, city centres and now even in the high Himalayan valleys is not limited to public health but will have consequences for agriculture, energy generation, migration and the glaciers.

The hot and dry conditions this week have already fanned wildfires across the Indian Himalaya and in western Nepal. Although not as bad as last year, Kathmandu has been shrouded in smoke haze for more than a month.

Having a good forecasting system in place will help with preparedness, and save lives. But Nepal does not yet have its own standards to determine heat or cold waves, and relying only on the World Meteorological Organisation has limitations when it comes to localised projections.

“Nepal needs to study its historical heat and cold waves and come up with its own standards and adjust it for the changing climate for better forecasting and preparedness at local levels,” says Pokharel.

The Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) in Kathmandu is monitoring the heat wave this week, and despite projections of higher solar intensity the smoke haze has also been filtering the sunlight, lowering the maximum temperature slightly.

“The heat wave conditions in the Indian plains this week is affecting us, and we expect more and more extreme heat events and anomalies made worse by the climate crisis,” says Archana Shrestha at the DHM.

She adds, “Average temperatures will continue to rise and we have no other recourse than to be prepared. This means we have to rethink our development pathways, I’m genuinely worried about how concrete structures are coming, this is turning our cities into hot spots. We must prepare this and future generations for even hotter summers. This means the the health, finance, agriculture ministries should all be prepared, not just the environment ministry.”