What future for snow leopards?

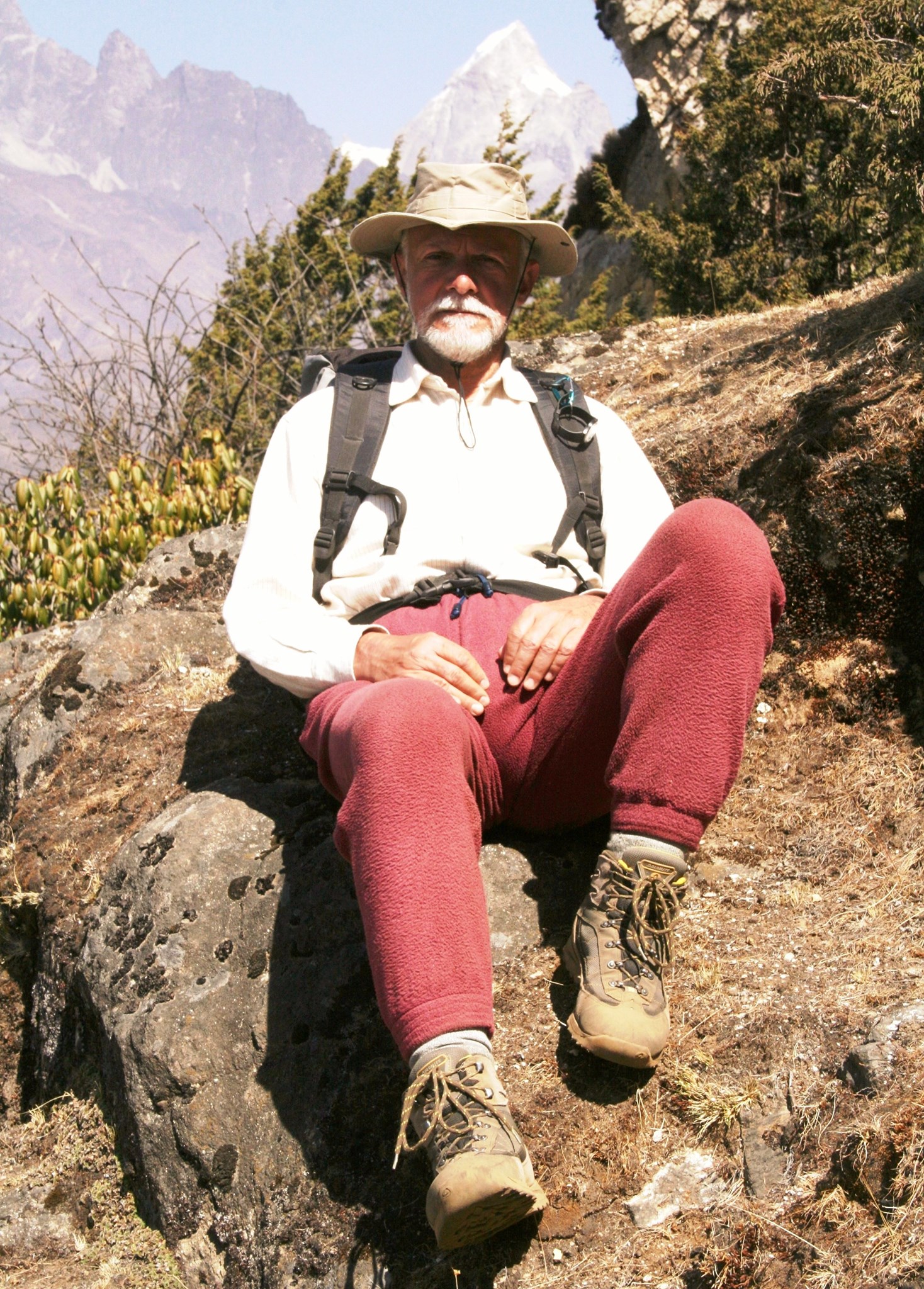

Beyond piecemeal initiatives to action to save snow leopardsSandro Lovari has led research expeditions on large mammals in Nepal and around the world for 50 years. He has been associated with the University of Cambridge UK, University of Groningen, Stockholm University, and Peking University. He has chaired the Steering Committee of the Snow Leopard Network since 2020. Nepali Times recently caught up with Lovari for an interview. Excerpts of the conversation:

Nepali Times: What is the ecological importance of snow leopards?

Sandro Lovari: Recent data show that predators are quite important not only to influence the spatial behaviour, but also the population dynamics of mountain ungulates. The snow leopard, as the main predator of bharal (naur), ibex and Himalayan tahr, plays the important ecological role of a top-down regulator of the populations of these herbivores, for example through differential age and sex predation patterns.

How have snow leopards been affected by herding and tourism?

Nearly all species of wild animals would gladly do without the invasive presence of Homo sapiens -- we have been the greatest enemies of wildlife, particularly for those species which we consider potential competitors, such as the large carnivores.

The snow leopard makes no exception. In the long run, the greater awareness of the public to save carnivores from decreasing may be dwarfed by the negative impacts of tourism.

How has the public perception of snow leopards changed over the years?

In the last 20 years, scientific papers on the snow leopard have seen a 20-fold increase. The renewed interest looks encouraging enough, but the quality may not match quantity, and we still lack information on some important biological issues.

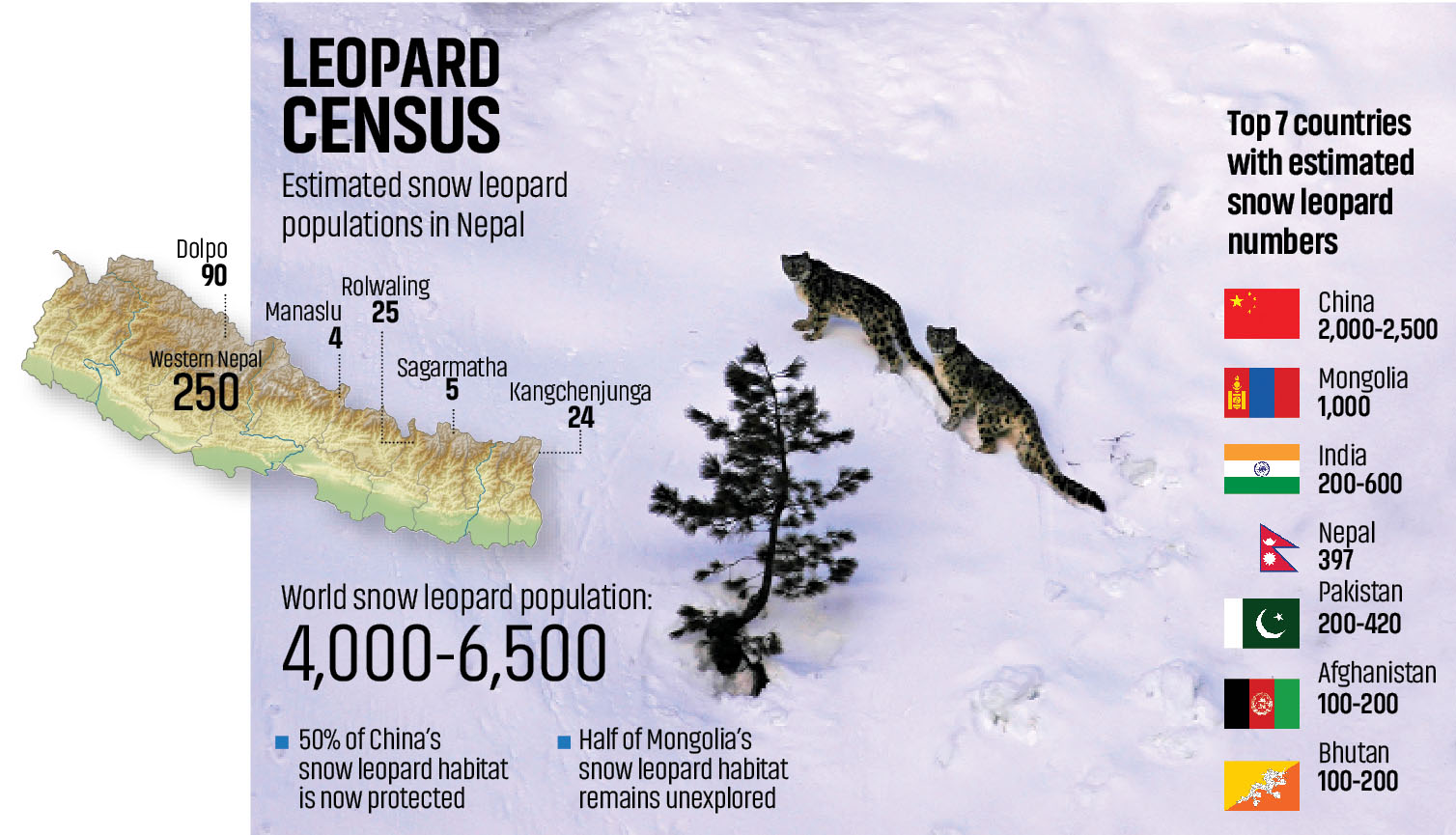

Long-term conservation measures require sound information, which is presently lacking, on numbers, distribution, dispersal patterns, prey-predator and predator-predator relationships, as well as social organisation of this species.

The use of camera-traps has allowed the collection of attractive pictures which has helped advertise this handsome cat. There were no pictures of a snow leopard in the wild until the ‘70s and the first extensive study on this species did not start until the early ‘80s.

Is the present information enough to help devise appropriate conservation measures?

Adequate protection of habitat comes first, but detailed information on ecological and behavioural issues is also quite important to plan conservation initiatives. Even the issue on its assumed territoriality has not been fully clarified yet.

The regulatory mechanisms of snow leopard populations, the predator-prey relationships and the snow leopard interactions with potentially competing predators are still unknown. In the last decade, most papers were based on camera-trapping to draw conclusions on snow leopard-wild prey-livestock relationships.

These studies have wrongly assumed that snow leopards and ungulates have the same probabilities to be detected by camera traps. The worst possible approach is to fragment funding into local exercises, with the aim of catching a few snow leopards, to fit them with radio-tags without appropriate research questions in mind, but only to gain visibility in the mass media. This would be deleterious for the conservation of the snow leopard, wasting money, time and credibility, eventually reaching no sensible goal.

How do you assess Nepal’s achievements in protecting snow leopard habitats?

I would say that the snow leopards of Nepal are doing fine. In fact, steps have been made to improve the tolerance of locals for this magnificent large cat, thanks to the action of several dedicated people and NGOs.

If I may provide a few suggestions: develop a well organised procedure to prevent and refund damage to livestock, develop a routine of annual or biennial counts of wild prey, at least within protected areas, using a robust count method, monitor the consequences of the ongoing thermal anomaly, be it a meteorological or a climatic one, on plants at higher elevations which is food for wild prey, and remain open to cooperation with experts, even from foreign countries.